It’s been hard to miss the scooter startup wars opening fresh, techno-fueled rifts in Valley society in recent months. Another flavor of ride-sharing steed which sprouted seemingly overnight to clutter up sidewalks — drawing rapid-fire ire from city regulators apparently far more forgiving of traffic congestion if it’s delivered in the traditional, car-shaped capsule.

Even in their best, most-groomed PR shots, the dockless carelessness of these slimline electrified scooters hums with an air of insouciance and privilege. As if to say: Why yes, we turned a kids’ toy into a battery-powered kidult transporter — what u gonna do about it?

An earlier batch of electric scooter sharing startups — offering full-fat, on-road mopeds that most definitely do need a license to ride (and, unless you’re crazy, a helmet for your head) — just can’t compete with that. Last mile does not haul.

But a short-walk replacement tool that’s so seamlessly manhandled is also of course easily vandalized. Or misappropriated. Or both. And there have been a plethora of scooter dismemberment/kidnap horror stories coming out of California, judging by reports from the scooter wars front line. Hanging scooters in trees is presumably a protest thing.

Scooter brand Lime struck an especially tone-deaf tech note trying to fix this problem after an update added a security alarm that bellowed robotic threats to call the cops on anyone who fumbled to unlock them. Safe to say, littering abusive scooters in public spaces isn’t a way to win friends and influence people.

Even when functioning ‘correctly’, i.e. as intended, scooter rides can ooze a kind of brash entitlement. The sweatless convenience looks like it might be mostly enabling another advance in tech-fueled douche behavior as a t-shirt wearing alpha nerd zips past barking into AirPods and inhaling a takeaway latte while cutting up the patience of pedestrians.

None of this fast-seeded societal friction has put the brakes on e-scooter startup momentum, though. Au contraire. They’ve been raising massive amounts of investment on rapidly inflating valuations ($2BN is the latest valuation for Bird).

But buying lots of e-scooters and leaving them at the mercy of human whim is an expensive business to try scaling. Hence big funding rounds are necessary if you’re going to replace all the canal-dunked duds and keep scooting fast enough for the competition.

At the same time, there isn’t a great deal to differentiate one e-scooter experience over another — beyond price and proximity. Branding might do it but then you have to scramble even harder and faster to create a slick experience and inflate a brand that sticks. (And it goes without saying that a scooter sticky with fecal-matter is absolutely not that.)

The still fledgling startups are certainly scrambling to scale, with some also already pushing into international markets. Lime just scattered ~200 e-scooters in Paris, for example. It’s also been testing the waters more quietly in Zurich. While Bird has its beady eye on European territory too.

The idea underpinning some very obese valuations for these fledgling startups is that scooters will be a key piece of a reworked, multi-modal transport mix for urban mobility, fueled by app-based convenience and city buy-in to greener transport options with emissions-free benefits. (Albeit scooters’ greenness depends on what they’re displacing; Great if it’s gas-guzzling cars, less compelling if it’s people walking or peddling.)

And while investors are buying in to the vision that lots of city dwellers are going to be scooting the last mile in future, and betting big on sizable value being captured by a few plucky scooter startups — more than half a billion dollars has been funneled into just two of these slimline scooter brands, Bird and Lime, since February — there are skeptical notes being sounded too.

Asking whether the scooter model really justifies such huge raises and heady valuations. Wondering if it isn’t a bit crazy for a fledgling Bird to be 2x a unicorn already.

Shared bike and scooter fleets are paving the way to a revolution in urban mobility but will only capture little value in the long term. Investors are highly overestimating the virtue of these businesses.

— Thibaud Elziere (@tiboel) June 18, 2018

The bear case for these slimline e-scooters says they’re really only fixing a pretty limited urban mobility problem. Too spindly and unsafe to go the distance, too sedate of pace (and challenged for sidewalk space) to feel worthwhile if you don’t have far to go anyway. And of course you’re not going to be able to cart your kids and/or much baggage on a stand-up two wheeler. So they’re useless for families.

Meanwhile scooter invasions are illegal in some places and, where they are possible, are fast inviting public and regulatory frisson and friction — by contributing to congestion and peril on already crowded pavements.

After taking one of Lime’s just-landed e-scooters for a spin in Paris this week, Willy Braun, VC at early stage European fund Daphni, came away unimpressed. “I didn’t feel I was really saving time in a short distance, since there is always many people in our narrow sidewalks,” he tells us. “And it isn’t comfortable enough for me to imagine a longer distance. Also it’s quite expensive ($1 per use and $.15/min).

“Lastly: Before renting it I read two news media that told me I had to use it only on the sidewalks and they tell us that we should only use it on the road during the onboarding — and that wearing an helmet is mandatory without providing it). As a comparison, I’d rather use e-bikes (or emoto-bikes) for longer journey without hesitation.”

“Give us Jump instead of Lime!” he adds, namechecking the electric bike startup that’s been lodged under Uber’s umbrella since April, adding a greener string to its urban mobility bow — and which is also heading over to Europe as part of the ride-hailing giant’s ongoing efforts to revitalize its regionally battered brand.

“Uber stands ready to help address some of the biggest challenges facing German cities: tackling air pollution, reducing congestion and increasing access to cleaner transportation solutions,” said CEO Dara Khosrowshahi wheeling a bright red Jump bike on stage at the Noah conference in Berlin earlier this month. Uber’s Jump e-bikes will launch in Germany this summer.

E-bikes do seem to offer more urban mobility versatility than e-scooters. Though a scooter is arguably a more accessible type of wheeled steed vs a bike, given you can just stand on it and be moved.

But in Europe’s dense and dynamic urban environments — which, unlike the US, tend to be replete with public transit options (typically at a spectrum of price-points) — individual transport choices tend to be based firstly on economics. After which it’s essentially a matter of personal taste and/or the weather.

Urban transport horses for courses — depending on your risk, convenience and comfort thresholds, thanks to a publicly funded luxury of choice. So scooters have loads of already embedded competition.

TechCrunch’s resident Parisienne, Romain Dillet — a regular user of on-demand bike services in the city (of which there are many), and prior to that the city’s own dock-based bike rental scheme — also went for a test spin on a Lime scooter this week. And also came away feeling underwhelmed.

“This is bad,” he said after his ride. “It’s slow and you need to brake constantly. BUT the worst part is that it feels waaaaaay more dangerous than a bike. Basically you can’t brake abruptly because you’re just standing there.”

Index Venture’s Martin Mignot was also in Paris this week and he took the chance to take a Lime scooter for a spin too — checking out the competition in his case, given the European VC firm is a Bird backer. So what did he think?

“The experience is pretty cool. It’s slightly faster than a bike, there’s no sweating. The weather was just amazing and very hot in Paris so it was pretty amazing in terms of speed and lack of effort,” he says, rolling out the positively spun, vested view on scooter sharing. “Especially going up hill to go to Gare du Nord.

“And the lack of friction — just to get on board and get started. So in general I think it’s a great experience and I think it feels a really interesting niche between walking and on-demand bikes… In Paris you’ve also got the mopeds. So that kind of ‘in between offering’. I think there’s a big market there. I think it’s going to work pretty well in Paris.”

Mignot is a tad disparaging about the quality of Lime’s scooters vs the model being deployed by Bird — a scooter model he also personally owns. But again, as you’d expect given his vested interests.

“Obviously I’m biased but I would say that the Xiaomi scooter/Ninebot scooter is higher quality than the one that Lime are using,” he tells us. “I thought that the Lime one, the handlebar is a little bit too high. The braking is a little bit too soft. Maybe it was the one I used, I don’t know.”

Talking generally about scooter startups, he says investors’ excitement boils down to trip frequency — thanks exactly to journeys being these itty-bitty last mile links.

But it’s also then about the potential for all that last mile hopping to be a shortcut for winning a prized slot on smartphone users’ homescreens — and thus the underlying game being played looks like a jockeying for prime position in the urban mobility race.

Lime, for example, started out with bike rentals before jumping into scooters and going multi-modal. So scooter sharing starts to look like a strategy for mobility startups to scoot to the top of the attention foodchain — where they’re then positioned to offer a full mix and capture more value.

So really scooters might mostly be a tool for catching people’s app attention. Think of that next time you see one lying on a sidewalk.

“What’s very interesting if you look at the trip distribution, most of the trips are short. So the vast majority of trips if you’re walking, obviously, are less than three miles. So that’s actually where the bulk of the mobility happens. And scooters play really well in that field. So in terms of sheer number of trips I think it’s going to dwarf any other type of transportation. And especially ride-hailing,” says Mignot.

“If you look at how often do people use Uber or Lyft or Taxify… it’s going to be much less frequent than the scooter users. And I think that’s what makes it such an interesting asset… The frequency will be much higher — and so the apps that power the scooters will tend to be on the homescreen. And kind of on top of the foodchain, so to speak. So I think that’s what makes it super interesting.”

Scooters also get a big investor tick on merit of the lack of friction standing in the way of riding vs other available urban options such as bikes (or, well, non-electric scooters, skateboards, roller blades, public transport, and so on and on) — in both onboarding (getting going) and propulsion (i.e. the lack of sweat required to ride) terms.

“That’s what’s so brilliant with these devices, you just snap the QR code and off you go,” he says. “The difference with bikes is that you don’t have to produce any effort. I think there are cases where obviously bikes are better. But I think there are a lot of cases where people will want something where you don’t sweat.

“Where you don’t wrinkle your clothes. Which goes a little bit faster. Without going all the way to the moped experience where you need to put the helmet, which is a bit more dangerous, which a lot of people, especially women, are not super familiar with. So I think what’s exciting with scooters as a form factor is it’s actually very mainstream.

“Anyone can ride them. It’s very simple to manoeuvre. It’s not super fast, it’s not too dangerous. It doesn’t require any muscular effort — so for older people or for people who just don’t want to sweat because they’re going to a meeting or something. It’s just a fantastic option.”

Index has also invested in an e-bike startup (Cowboy) and the firm is fully signed up to the notion that urban mobility will be multimodal. So if e-scooters valuations are a bit overcooked Index is not going to be too concerned. People in cities are clearly going to be riding something. And backing a mix is a smart way to hedge the risk of any one option ending up more passing fad than staple urban steed.

Mostly Index is betting that people will keep on riding robotic horses for urban courses. And whatever they ride it’s a fairly safe bet that an app is going to be involved in the process of finding (docklessness is therefore another attention play) or unlocking (scan that QR code!) the mobility device — opening up the possibility that a single app could house multiple mobility options and thus capture more overall value.

“It’s not a one-size fits all. They’re all complementing each other,” says Mignot of the urban mobility options in play. “I would say e-bikes are probably a little bit more great for little bit longer trips because you’re sitting down. But again it takes a little bit longer, because you have to adjust the saddle, you need to start peddling. There’s a bit more friction both on the onboading and on the riding. But they’re a bit better for slightly longer distances. I would say for shorter distances there’s nothing better than the scooter.”

He also points out that scooters are both cheaper and less bulky than e-bikes. And because they take up less street space they can — at least in theory — be more densely stacked, thereby generating the claimed convenience by having them sitting near enough to convince someone not to bother walking 10 minutes to the café or gym — and just scoot instead. So scooters’ slimline physique is also especially exciting to investors. (Even if, ironically, it’s being deployed to urge people to walk less.)

“I think we will end up with more density of scooters. Which is super important,” he continues. “People will, in the end, tend to take the vehicle that they can find where they are. And I think it’s more likely, eventually, that they will get a scooter than an e-bike. Just simply because they take less space and they are less expensive.”

But why wouldn’t people who do get won over to the sweatless perks of last mile scooting just buy and own their own ride — rather than shelling out on an ongoing basis to share?

Unlike bikes, scooters are mobile enough to be picked up and moved around fairly easily. Which means they can go with you into your home, office, even a restaurant — disruptively reducing theft risk. Whereas talk to any bike owner and they’ll almost invariably have at least one tale of theft woe, which is a key part of what makes bike sharing so attractive: It erases theft worry.

Add to that, you can find e-scooters on sale in European electronics shops for as little as €140. So if you’re going to be a regular scooterer, the purely economic argument to just own your own looks pretty compelling.

And people zipping around on e-scooters is a pretty common sight in another dense European city, Barcelona, which has very scooter-friendly weather but no scooter startups (yet). But unless it’s a tourist weaving along the seafront most of these riders are not shared: People just popped into their local electronics shop and walked out with a scooter in a box.

So the rides aren’t generating repeat revenue for anyone except the electricity companies.

Asked why people who do want to scoot won’t just buy, rather than rent Mignot talks up the hassle of ownership — undermined slightly by the fact he is also a scooter owner (despite the claimed faff from problems such as frequent flat tires and the chore of the nightly charge).

“The thing you notice very rapidly: There are two things, one is the maintenance,” he says. “The models that exist today are not super robust. Maybe in a very flat, very smooth roads, maybe Santa Monica, maybe it’s a little bit less true but I would say in Europe the maintenance that is required is fairly high… I have to do something on mine every week.

“The other thing is it takes a little bit of space. If you have to bring it to a restaurant or whatever type of crowded place, a movie theatre or wherever you’re going, to an office, to a meeting room, it’s a little bit on the heavy side, and it’s a little bit inconvenient. So certainly some people will buy them… But I also think that there are a lot of cases where you’d rather have it just on-demand.”

Unlike Mignot and Index, Tom Bradley, of UK focused VC firm Oxford Capital, is not so convinced by the on-demand scooter craze.

The firm has not made any e-scooter investments itself, though mobility is a “core theme”, with the portfolio including an on-demand coach travel startup (Sn-ap), and technology plays such as Morpheus Labs (machine learning for driverless cars) and UltraSoc (complex circuits for automotive parts, which sells to the likes of Tesla).

But it’s just not been sold on scooter startups. Bradley describes it as an “open question” whether scooters end up being “an important part of how people move around the cities of the future”. He also points to theft problems with dockless bike share schemes that have not played out well in the UK.

“We’re not convinced that this is a fundamental part of the picture,” he says of scooter sharing. “It may be a part of the picture but I personally am not yet convinced that it’s as big a part of the picture that people seem to be prepared to pay for.”

“I keep thinking of the Segway example,” he adds. “It’s an absolutely delightful product. It’s brilliant. It’s absolutely brilliant. In a way that these electric scooters are not. But obviously it was much more expensive. And it made people feel a bit weird. But it was supposed to be the answer — and it’s not the answer. Before its time, perhaps.”

Of course he also accepts that capital is “being used as a weapon”, as he puts it, to scoot full-pelt towards a future where shared electric scooters are the norm on city streets by waging a “marketing war” to get there.

“Venture capital valuations are what someone is prepared to pay. And in this case people are valuing potential rather than valuing the business… so the valuations [of Bird and Lime] are being driven more than anything by the amount of money being raised,” he says. “So you decide a rule of thumb about what is acceptable dilution, and if you’re going to raise $400M or whatever then the valuation’s got to be somewhere between $1.6BN and $2BN to make that sort of raise make sense — and leave enough equity for the previous investors and founders. So there’s an element of this where the valuations are being driven by the amount of capital being raised.”

Oxford Capital’s bearish view on scooter sharing is also bounded by the fund only investing in UK-based startups. And while Bradley says it sees lots of local mobility strengths — especially in the automotive market — he admits it’s more of a mental leap to imagine a world leading scooter startup sprouting from the country’s green and pleasant lands. Not least because it’s not legal to use them on UK public roads or pavements.

“If you look at places like Amsterdam, Berlin, they’re sort of built for bikes. London’s getting towards being built for bikes… Cycling’s been one of the big success stories in London. Is [scooter sharing] going to replace cycling? I don’t know. Not so convinced… It’s obviously easy for anyone to get on and off these things, young and old. So that’s good, it’s inclusive. But it feels a little bit like a solution looking for a problem, the sorts of journeys people talk about for these things — on campus, short urban journeys. A lot of these are walkable or cycle journeys in a lot of cities. So is there a mass need?

“Is this Segway 2 or is this bike hire 2… it’s hard to tell. And we’re coming down on the former. We’re not convinced this is going to be a fundamental part of the transport space. It will be a feature but not a huge part.”

But for Mignot the early days of the urban mobility attention wars mean there’s much to play for — and much that can be favorably reshaped to fit scooters into the mix.

“The whole thing, even on-demand bikes, it’s a two year old phenomenon really,” he says. “So I think everyone is just trying to learn and figure out and adapt to this new reality, whether it’s users or companies or cities. I think it’s very similar to when cars were first introduced. There were no parking spaces at the time and there were no rules on the road. And fast forward 100 years and it looks very different.

“If you look at the amount of infrastructure and effort and spend that has been put into making — and I would argue way more than should have — into making a city car-friendly, if you only do a 100th of the same amount of effort and spend into making some space for bicycles and light two-wheel vehicles I think we’ll be fine.

“That’s the beauty of this model. If you compare the space of the tech and if you look at the efficiency of moving people around vs the space, the scooters are simply the most efficient because their footprint on the ground is just so small.”

He even makes the case for scooters working well in London — arguing the sprawl of the city amps up the utility because there are so many tedious last mile trips that people have to make.

Even more so than in denser European cities like Paris, where he admits that hopping on a scooter might just be more of a “nice to have”, given shorter distances and all the other available options. So, really, where urban mobility is concerned, it can actually be courses for horses.

Yet, the reality is London is off-limits to the likes of Bird and Lime for now — thanks to UK laws barring this type of unlicensed personal electric vehicle from public roads and spaces.

You can buy e-scooters for use on private land in the UK but any scooter startups that tried their usual playbook in London would be scooting straight for legal hot water.

It’s not just the British weather that’s inclement.

“I’m really hoping that TfL [Transport for London] and the Department for Transport are going to make it possible,” says Mignot on that. “I think any city should welcome this with open arms. Some cities are, by the way. And I think over time once they see the success stories in other parts of the world I think they all will. But I wish London was one of those cutting edge cities that would welcome new innovation with open arms. I think right now, unfortunately, it’s not there.

“There’s a lot of talk about air quality, and so on, but actually, when push comes to shove… you have a lot of resistance and a lot of pushback… So it’s a little bit disappointing. But, you know, we’ll get there eventually.”

Powered by WPeMatico

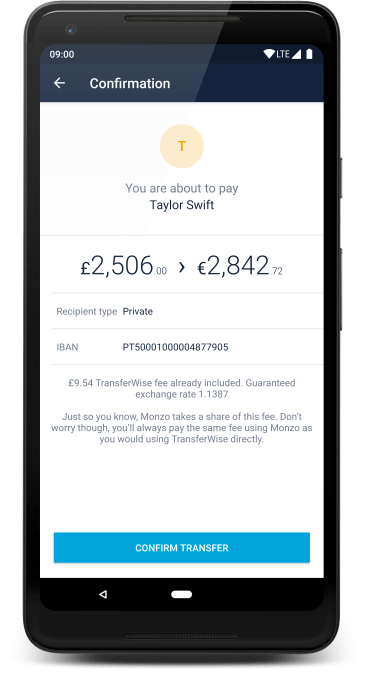

The TransferWise functionality will start rolling out to Monzo users as of today and will let them send money from their current accounts to 18 of the most popular currencies, with “more being added in the near future”. The user experience will be near-identical to TransferWise’s own app, and will see transfers happen at claimed ‘mid-market’ rates in addition to TransferWise’s low and transparent fee. This means you’re told upfront exactly how much you’ll pay in fees and the amount you’ll receive in the exchanged currency.

The TransferWise functionality will start rolling out to Monzo users as of today and will let them send money from their current accounts to 18 of the most popular currencies, with “more being added in the near future”. The user experience will be near-identical to TransferWise’s own app, and will see transfers happen at claimed ‘mid-market’ rates in addition to TransferWise’s low and transparent fee. This means you’re told upfront exactly how much you’ll pay in fees and the amount you’ll receive in the exchanged currency.