TC

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

The American South may not be the first region that comes to mind when you hear the phrase “hotbed of tech entrepreneurship,” but, slightly misguided perceptions aside, it’s home to a diverse and growing collection of startups.

Here, we’re going to take a deep dive into the startup funding data for the region.

Just like it’s a common pastime for many city dwellers to argue about the precise boundaries of neighborhoods, there’s often some disagreement about the exact contours of the U.S.’s various regions. To quash rabble-rousing from the get-go, we’re using the U.S. Census Bureau’s definition of “the South” on its official map of the United States. Below, we display a map of the states we’re going to look at today.

Much like barbecue, the South is not a monolithic concept. So to incorporate some regional flavor into the following analysis, we’re also going to use the same regional divisions that the U.S. Census Bureau uses.

By doing this, we’ll be able to get a better idea of the relative contribution states from each sub-region make to startup activity in the South overall.

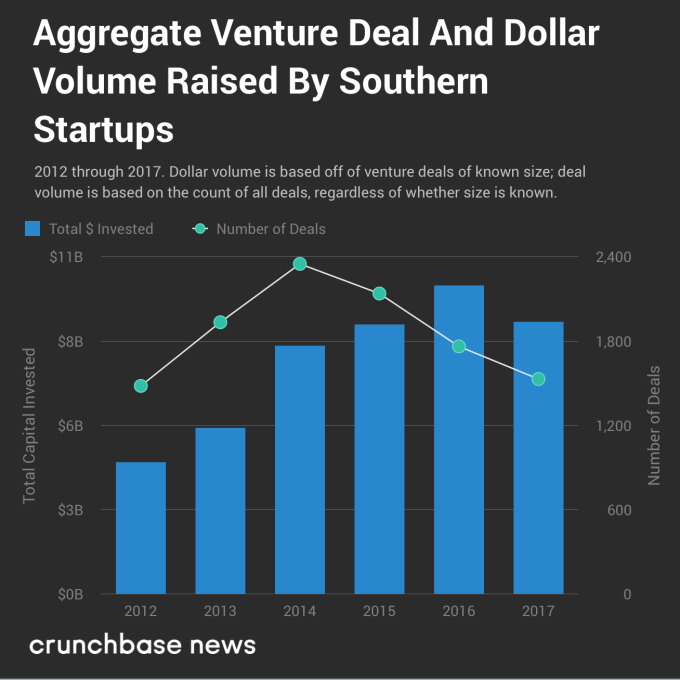

As is the case with most of the country, the South appears to be experiencing a shift in startup funding as we move toward the latter half of a bull run in entrepreneurial activity. The chart below shows a divergence in overall deal and dollar volume over time.

Much like in the rest of the U.S., reported deal and dollar volume are heading in different directions. Part of this may be due to reporting delays — it can sometimes take a few years for seed and early-stage rounds to get added to databases like Crunchbase’s . Nonetheless, there is a slow and generally upward creep in round sizes at most stages of funding. And that’s not just a Southern thing; it’s a country-wide trend.

Let’s disaggregate these figures a bit. We’ll start with deal counts and move on to dollar volume from there.

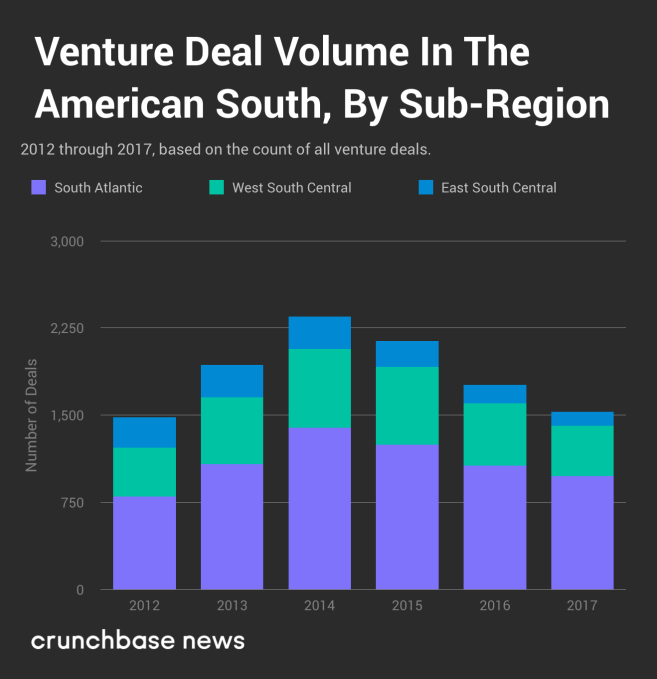

In the chart below, you’ll see venture deal volume broken out by sub-region.

Over the past several years, reported venture deal volume has been on the downswing. From a local maximum in 2014 through the end of 2017, it’s down almost 35 percent overall. But that’s not the whole picture. The relative share of deal volume has changed, as well.

Although it’s not immediately clear just by looking at the chart above, startups in the South Atlantic sub-region have accounted for an increasingly large share of the funding rounds. For example, in 2012, South Atlantic startups attracted 54 percent of the deal volume. In 2017, that grows to 64 percent. Startups in the West South Central sub-region have pretty consistently pulled in between 28 and 30 percent of the deals, so where’s the loss coming from? Startups headquartered in Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi and Alabama pulled in just 8 percent of deals in 2017, compared to 18 percent in 2012.

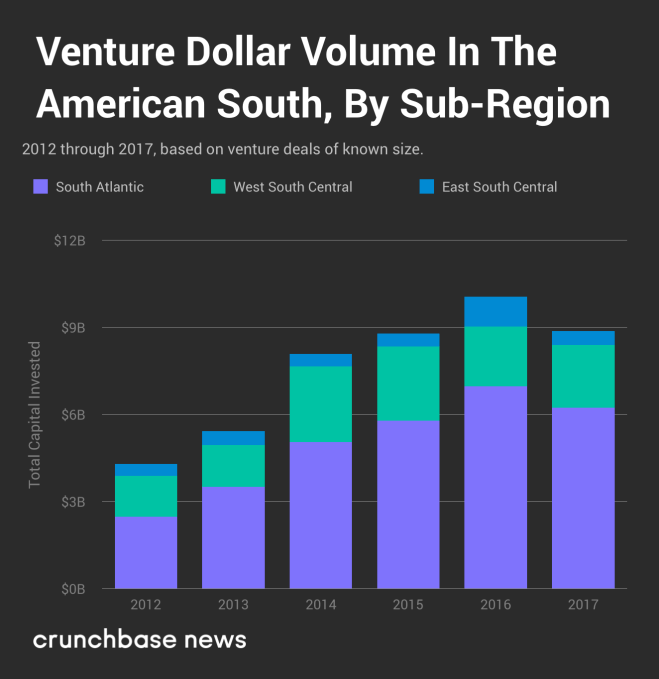

It’s a similar story with dollar volume.

In general, dollar volume follows the same pattern, albeit with a bit more variability. Regardless, startups in the South Atlantic sub-region are hoovering up an ever-larger share of venture dollars, and there’s little to indicate that trend will reverse itself any time soon.

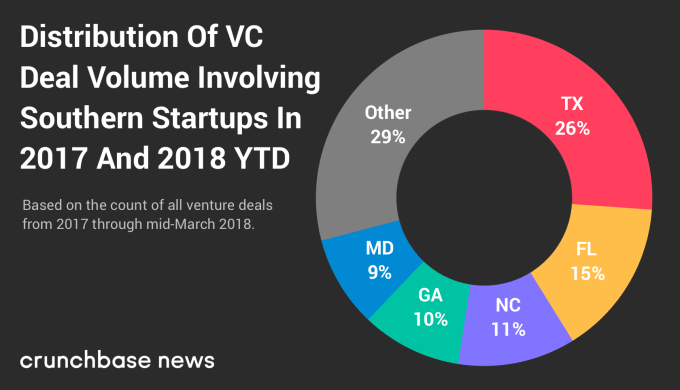

Let’s see which states accounted for most of the deal volume. The chart below shows the geographic distribution of deal-making activity by startups in each Southern state from the beginning of 2017 through time of writing. It should come as no surprise that much of the activity is concentrated in states with higher populations.

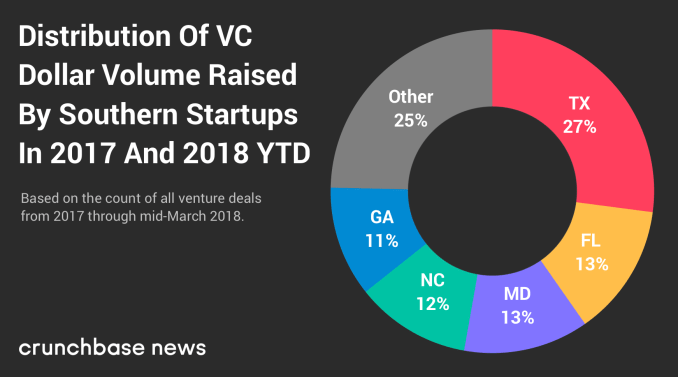

And here’s the distribution of dollar volume among southern states.

Despite some variation in which states are at the top of the ranks, the share of deal and dollar volume raised by startups in the top three states is remarkably similar, coming in at between 52 and 53 percent for both metrics.

We started by looking at the South as a whole and then drilled into its sub regions and states. But there’s one layer deeper we can go here, and that’s to rank the top startup cities in the South.

In the interest of keeping our rankings fresh and timely, we’re covering activity from the past 15 months or so, from the start of 2017 through mid-March 2018. But before highlighting some of the more notable hubs, let’s take a look at the numbers.

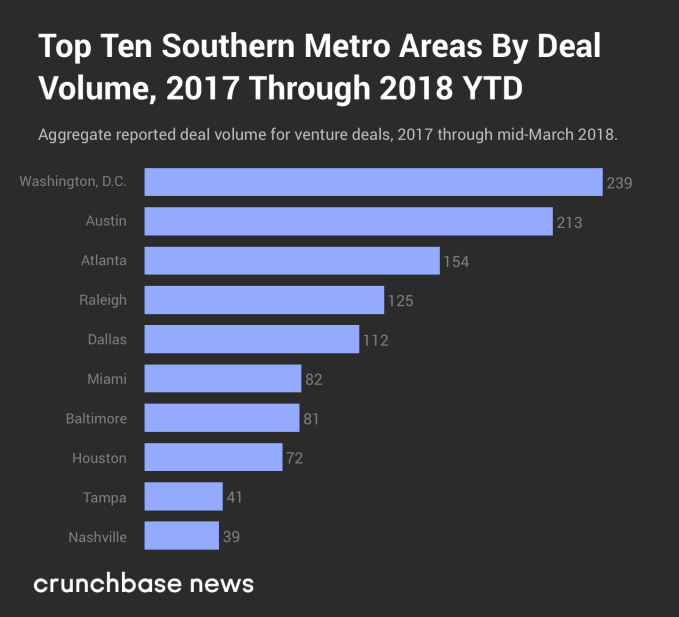

In the chart below, you’ll find the top 10 metropolitan areas where Southern startups closed the most funding rounds.

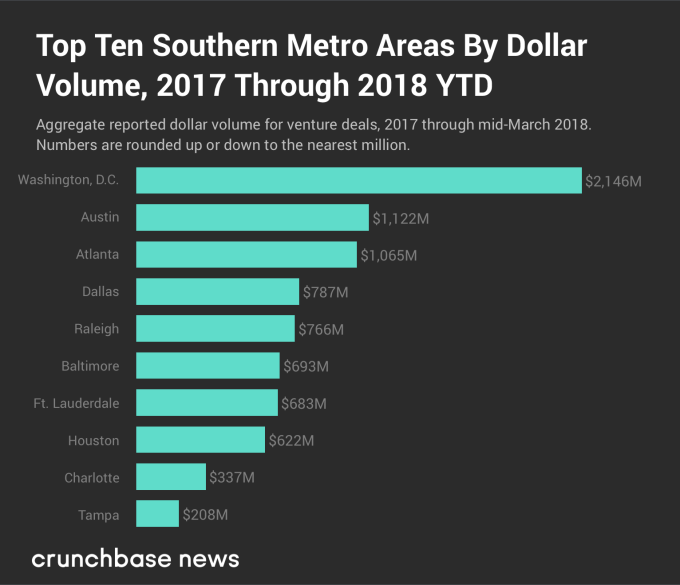

The chart below shows reported dollar volume over the same period of time.

Much like we saw at the state level, the top five startup cities — ranked by both deal and dollar volume — are the same, although there’s some variation between where each one ranks. In order, the D.C., Austin and Atlanta metro areas rank in the top three for each metric, while Dallas and Raleigh, NC switch off between fourth and fifth place.

To be frank, Washington, D.C.’s top-shelf ranking was a bit of a surprise. It may be the fact that Austin, TX plays host to South By Southwest, a somewhat more relaxed culture and/or a preponderance of excellent breakfast taco and barbecue joints, but to many — ourselves included — the city feels like it would have a more active startup scene than the nation’s capital. But that’s not exactly the case. The D.C. metro area had more venture deal and dollar volume than Austin for seven out of the last 10 years, and startups based in the nation’s capital have raised more than twice as much money so far in 2018.

D.C.-area startups have recently raised some notable rounds. Just a couple of weeks prior to the time of writing, Viela Bio raised $250 million in a Series A round (in late February 2018) to continue funding research and testing of its treatments for severe inflammation and autoimmune diseases. And on the later-stage end of things, education technology company Everfi raised $190 million in a Series D round that had participation from Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos, former Alphabet executive Eric Schmidt and Medium CEO Ev Williams. Other D.C. companies, including Mapbox, Upside.com, Afiniti and ThreatQuotient, have all raised late-stage rounds within the past 15 months.

Startup ecosystems in Southern cities may pale in comparison to places like New York and San Francisco, but it wouldn’t be wise to discount the region entirely. A large number of interesting companies call the lower half of the Lower 48 home, and as the cost of living continues to rise on the east and west coasts, don’t be surprised if many current and would-be founders opt to stay down home in the South.

Powered by WPeMatico

It seems like startup news is full of overnight success stories and sudden failures, like the scooter rental company that went from zero to a $300 million valuation in months or the blood-testing unicorn that went from billions to nearly naught.

But what about those other companies that mature more gradually? Is there such a thing as slow and successful in startup-land?

To contemplate that question, Crunchbase News set out to assemble a data set of top late-blooming startups. We looked at companies that were founded in or before 2010 that raised large amounts of capital after 2015, and we also looked at companies founded a least five years ago that raised large early-stage funds in the last year. (For more details on the rules we used to select the companies, check “Data Methods” at the end of the post.)

The exercise was a counterpoint to a data set we did a couple of weeks ago, looking at characteristics of the fastest growing startups by capital raised. For that list, we found plenty of similarities between members, including a preponderance of companies in a few hot sectors, many famous founders and a lot of cancer drug developers.

For the late bloomers, however, patterns were harder to pinpoint. The breakdown wasn’t too different from venture-backed companies overall. Slower-growing companies could come from major venture hubs as well as cities with smaller startup ecosystems. They could be in biotech, medical devices, mobile gaming or even meditation.

What we did find, however, was an interesting and inspiring collection of stories for those of us who’ve been toiling away at something for a long time, with hopes still of striking it big.

Even youthful startups have been known to make a major pivot or two. So it’s not surprising to see a lot of pivots among late bloomers that have had more time to tinker with their business models.

One that fits this mold is Headspace, provider of a popular meditation app. The company, founded in 2010 by a British-born Buddhist monk with a degree in circus arts, started as a meditation-focused events startup. But it turned out people wanted to build on their learning on their own time, so Headspace put together some online lessons. Today, Santa Monica-based Headspace has millions of users and has raised $75 million in venture funding.

For late bloomers, the pivot can mean going from a model with limited scalability to one that can attract a much wider audience. That’s the case with Headspace, which would have been limited in its events business to those who could physically show up. Its online model, with instant, global reach, turns the business into something venture investors can line up behind.

They say if you wait long enough, everything comes back in style. That mantra usually works as an excuse for hoarding ’80s clothes in the attic. But it also can apply to entrepreneurial companies, which may have launched years before their industry evolved into something venture investors were competing to back.

Take Vacasa, the vacation rental management provider. The company has been around since 2009, but it began raising VC just a couple of years ago amid a broad expansion of its staff and property portfolio. The Portland-based company has raised more than $140 million to date, all of it after 2016, and most in a $103 million October round led by technology growth investor Riverwood Capital.

CloudCraze, which was acquired by Salesforce earlier this week, also took a long time to take venture funding. The Chicago-based provider of business-to-business e-commerce software launched in 2009, but closed its first VC round in 2015, according to Crunchbase records. Prior to the acquisition, the company raised about $30 million, with most of that coming in just a year ago.

Meanwhile, some late bloomers have always been fashionable, just not necessarily as VC-funded companies. Untuckit, a clothing retailer that specializes in button-down shirts that look good untucked, had been building up its business since 2011, but closed its first venture round, a Series A led by VC firm Kleiner Perkins, last June.

So yes, there is still capital available for those who wait. However, the truth of the matter is most companies that raise substantial sums of venture capital secure their initial seed rounds within a couple years of founding. Companies that chug along for five-plus years without a round and then scale up are comparatively rare.

That said, our data set, which looks at venture and seed funding, does not come close to capturing the full ecosystem of slow-growing startups. For one, many successful bootstrapped companies could raise venture funding but choose not to. And those who do eventually decide to take investment may look at other sources, like private equity, bank financing or even an IPO.

Additionally, the landscape is full of slow-growing startups that do make it, just not in a venture home run exit kind of way. Many stay local, thriving in the places they know best.

On the flip side, companies that wait a long time to take VC funding have also produced some really big exits.

Take Atlassian, the provider of workplace collaboration tools. Founded in 2002, the Australian company waited eight years to take its first VC financing, despite plentiful offers. It went public two years ago, and currently has a market valuation of nearly $14 billion.

The moral: Those who take it slow can still finish ahead.

Data methods

We primarily looked at companies founded in 2010 or earlier in the U.S. and Canada that raised a seed, Series A or Series B round sometime after the beginning of last year, and included some that first raised rounds in 2015 or later and went on to substantial fundraises. We also looked at companies founded in 2012 or earlier that raised a seed or Series A round after the beginning of last year and have raised $30 million or more to date. The list was culled further from there.

Powered by WPeMatico

There’s a new twist in the BroadQualm saga this afternoon as Qualcomm has said it won’t renominate Paul Jacobs, the former executive chairman of the company, after he notified the board that he decided to explore the possibility of making a proposal to acquire Qualcomm.

The last time we saw such a huge exploration to acquire a company was circa 2013, when Dell initiated a leveraged buyout to take the company private in a deal worth $24.4 billion. This would be of a dramatically larger scale, and there’s a report by the Financial Times that Jacobs approached Softbank as a potential partner in the buyout. Jacobs is the son of Irwin Jacobs, who founded Qualcomm, and rose to run the company as CEO from 2005 to 2014. Successfully completing a buyout of this scale would, as a result, end up keeping the company that his father founded in 1985 in the family.

“I am glad the board is willing to evaluate such a proposal, consistent with its fiduciary duties to shareholders,” Jacobs said in a statement. “It is unfortunate and disappointing they are attempting to remove me from the board at this time.”

All this comes following Broadcom’s decision to drop its plans to try to complete a hostile takeover of Qualcomm, which would consolidate two of the largest semiconductor companies in the world into a single unit. Qualcomm said the board of directors would instead consist of just 10 members.

“Following the withdrawal of Broadcom’s takeover proposal, Qualcomm is focused on executing its business plan and maximizing value for shareholders as an independent company,” the company said in a statement. “There can be no assurance that Dr. Jacobs can or will make a proposal, but, if he does, the Board will of course evaluate it consistent with its fiduciary duties to shareholders.”

Broadcom dropped its attempts after the Trump administration decided to block the deal altogether. The BroadQualm deal fell into purgatory following an investigation by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, or CFIUS, and then eventually led to the administration putting a stop to the deal — and potentially any of that scale — while Broadcom was still based in Singapore. Broadcom had intended to move to the United States, but the timing was such that Qualcomm would end up avoiding Broadcom’s attempts at a hostile takeover.

BroadQualm has been filled with a number of twists and turns, coming to a chaotic head this week with the end of the deal. Qualcomm removed Jacobs from his role as executive chairman and installed an independent director, and then delayed the shareholder meeting that would give Broadcom an opportunity to pick up the votes to take over control of part of Qualcomm’s board of directors. The administration then handed down its judgment, and Qualcomm pushed up its shareholder meeting as a result to ten days following the decision.

“There are real opportunities to accelerate Qualcomm’s innovation success and strengthen its position in the global marketplace,” Jacobs said in the statement. “These opportunities are challenging as a standalone public company, and there are clear merits to exploring a path to take the company private in order to maximize the company’s long-term performance, deliver superior value to all stockholders, and bolster a critical contributor to American technology.”

It’s not clear if Jacobs would be able to piece together the partnerships necessary to complete a buyout of this scale. But it’s easy to read between the lines of Qualcomm’s statement — which, as always, has to say it will fulfill its fiduciary duty to its shareholders. The former CEO and executive chairman has quietly been a curious figure to this whole process, and it looks like the BroadQualm saga is nowhere near done.

Powered by WPeMatico

Developer bootcamps — several-month training programs that are designed to help people get up to speed with the technical skills they need to become a developer — exploded in popularity in the early part of the decade, but there’s been a bit of a shakedown on the space recently.

And that could be a product of a lot of things, but for Jacob Hess and Terry Kim, it’s just not enough time to become a fully-fledged developer. With training in the Air Force, where both had to work on these kinds of compressed programs for entry-level technicians, both decided to try their own approach. The end result is NexGenT, which is own kind of bootcamp — but it’s for getting a certificate in network management, and not a one-size-fits-all sticker as a developer. That approach, which includes a 16-week class, is considerably more reasonable and helps get people industry-ready with a skill that’s teachable in that compressed period of time, Hess says. The company is launching out of Y Combinator’s winter class this year.

“There are 500,000 open IT jobs, but when you look at that number, what’s more interesting is so many of them are IT operation roles, and the remaining is software development,” Hess said. “The bigger pie in IT is non-software programming jobs. Cyber security is also huge because of the automation and AI. We want to create the stepping stone. Network engineering becomes a foundation for a lot of these jobs, whether you want to be a cloud architect and work for Amazon, it all starts with understanding and building a foundation around networking.”

The end result is a 16-week program where a batch of applicants gets a review, and a percentage of them are accepted into a cohort of students. They go through an engineering module, which teaches them the basics and mechanics of network engineering and learn about the IT industry. Students can go faster if they want — it’s primarily online — and then start working on labs where they are building their own lab, either physical or virtual. The process culminates in a project where the students have to roll out an HQ facility in two branch offices from design to technically implementing it.

The next phase is about getting them certifications for various technologies, which help them basically show that they are ready to start entering the workforce. Think of it as something similar to having a Github account where prospective employers can review the work, except the process is a lot more formalized and you end up with something concrete on the resume. The final phase is around career coaching and helping them get a job, which can last up to 6 months. Throughout this process, students have access to a mentor and live coaching where students can ask whatever questions they wish.

So, the process is not so dissimilar from the notion of a developer bootcamp. But at the same time, there’s a small-ish graveyard of developer bootcamps and some with issues. Galvanize in August said it would lay off around 11% of its staff, while Dev Bootcamp and Iron Yard shut down altogether. The knock on these camps is it’s hard to get developers ready to start shipping code in such a small period of time — but Kim argues that getting them certified and ready to be a network engineer is definitely something that’s doable in around 16 weeks.

“It’s more realistic,” Kim said. “For coding bootcamps, you have to go by off the portfolios and check their Github, and they have to pass that technical interview. In our world of IT operations, it’s not about the bachelor’s degree, it’s about the person having the knowledge. But the industry certifications come from third parties, and when they come out of our program and have two or three certifications. It’s enough to get into that entry-level job.”

It remains to be seen if this kind of an approach is going to work. NexGenT charges a tuition — around $12,000, which with maximum discounts hits around $6,500. The company offers a 36-month payment plan as well that comes with an enrollment fee, which stretches out that very steep ticket price. In reality, these zero-to-60 programs are designed to be for-profit, though there are some different models that take in a percentage of salary among other approaches. With that in mind, though, there’s always an opportunity to build a strong pipeline with certain companies, and if they can identify high-performing students they can offer more of a proof point and potentially use that as an opportunity to offer some variation of scholarship.

While this is more of a bootcamp-ish style program, there are already some IT certification programs through tools like Coursera. Google, in one instance, is offering financial aid for a batch of those students, and companies with deep pockets might be able to build out these kinds of pipeline programs on their own. Hess and Kim hope to offer some kind of high-touch approach, instead of just a class on a platform of many, that will give them an edge to be a preferred option.

Powered by WPeMatico

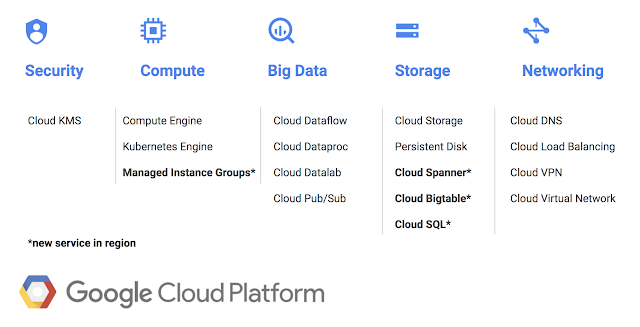

Google today announced that it has expanded its recently launched Cloud Platform region in the Netherlands with an additional zone. The investment, which is worth a reported 500 million euros, expands the existing Netherlands region from two to three regions. With this, all four of the Central European Google Cloud Platform zones now feature three zones (which are akin to what AWS would call “availability zones”) that allow developers to build highly available services across multiple data centers.

Google typically aims to have a least three zones in every region, so today’s announcement to expand its region in the Dutch province of Groningen doesn’t come as a major surprise.

With this move, Google is also making Cloud Spanner, Cloud Bigtable, Managed Instance Groups, and Cloud SQL available in the region.

Over the course of the last two years, Google has worked hard to expand its global data center footprint. While it still can’t compete with the likes of AWS and Azure, which currently offers more regions than any of its competitors, the company now has enough of a presence to be competitive in most markets.

In the near future, Google also plans to open regions in Los Angeles, Finland, Osaka and Hong Kong. The major blank spots on its current map remain Africa, China (for rather obvious reasons) and Eastern Europe, including Russia.

Powered by WPeMatico

The first post-billion, big tech IPO of the year has opened with a bang. Zscaler, a security startup that confidentially filed for an IPO last year, closed out its first day of trading at $33/share, up 106% from its opening price of $16.

The enterprise cloud services company started trading this morning as ZS on Nasdaq at a price of $27.50/share, a pop of 71.9 percent on its opening price, and its stock today reached a peak of $33.37. The activity on Zscaler could point to a bullish moment for security startups, and potentially public listings for tech companies in general — as well as some pent-up demand in a climate that has been somewhat dry for big tech IPOs after some notable flops.

That could bode well for Dropbox, Spotify and others that are planning or considering public listings in the coming weeks and months.

Zscaler, a cloud-services company, posted revenues of $125.7 million in 2017 with net losses of $35.5 million and said in its S-1 that it expected to “continue to incur net losses for the foreseeable future.” But it priced its IPO modestly, and the result was that there seemed to be more of an appetite for the company than expected.

Initially, Zscaler had expected to sell 10 million shares at a range between $10 and $12 per share, but interest led the company to expand that to 12 million shares at a $13-15 range, which then moved up to $16 and Zscaler last night raising $192 million giving it a valuation of over $1.9 billion — a sign of strong interest in the investor community that it’s now hoping will follow through in its debut and beyond.

Zscaler is a specialist in an area called software-defined perimeter (SDP) services, which allow enterprises and other organizations to better control how they allow employees to access apps and specific services within their IT networks: the idea is that rather than giving access to the full network, employees are authenticated just for the apps that they specifically need for their work.

SDP architectures have become increasingly popular in recent years as a way of better mitigating security threats in networks where employees are using a variety of devices, including their own private mobile phones, to access data and apps in corporate networks and in the cloud — both of which have become routes for malicious hackers to breach systems.

SDP services are being adopted by the likes of Google, and are being built by a number of other tech companies, both those that are looking to provide more value-added services around existing cloud or other IT offerings, and those that are already playing in the area of security, including Cisco, Check Point Software, EMC, Fortinet, Intel, Juniper Networks, Palo Alto Networks, Symantec (which has been involved in IP lawsuits with Zscaler) and more — which speaks both of the opportunity and challenge in the market for Zscaler. Estimates of the value of the market range from $7.8 billion to $11 billion by 2023.

Go here for more on the IPO, and hear from the CEO himself.

Powered by WPeMatico

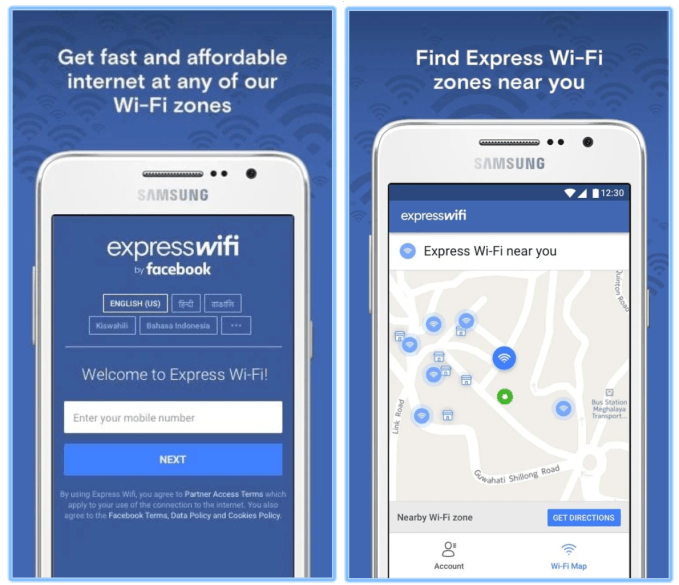

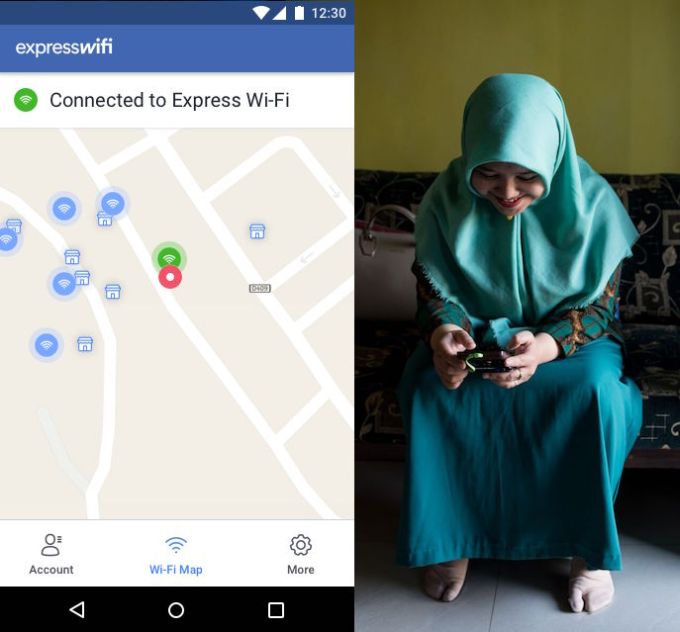

Facebook wants you to pay for internet. This week TechCrunch was tipped off that Facebook had quietly launched an Express Wi-Fi Android app in the Google Play store that lets users buy data packs and find nearby hotspots as part of Facebook’s distributed Wi-Fi network. The company’s Express Wi-Fi program is live in five developing countries that see local business owners operating Wi-Fi hotspots where people can pay to access higher-speed bandwidth via local telecoms instead of paying steep prices for slow cellular data connections.

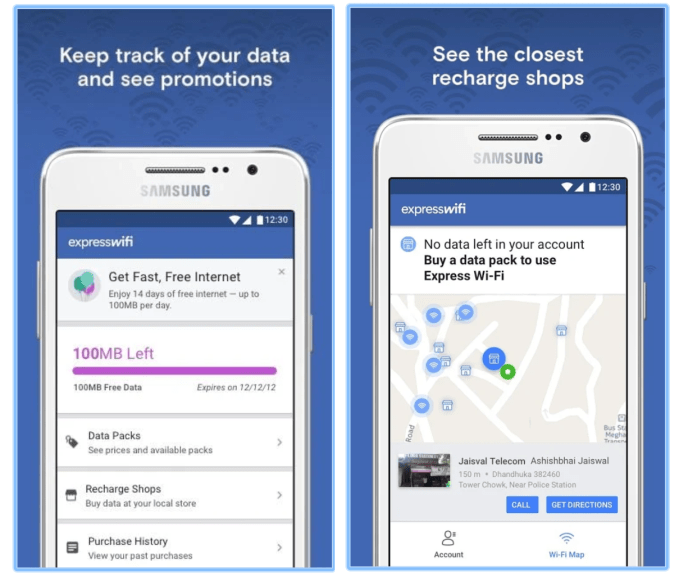

Previously, Express Wi-Fi users had to dig out a mobile website, or directly download an app from a telecom that required reconfiguring a phone’s settings. There wasn’t any way to look up where hotspots were located. The new Google Play app can be downloaded the normal way. It’s now live in Indonesia with bandwidth from telecom partner D-Net, and in Kenya through Surf. The app can also tell if a user’s Wi-Fi is turned on to help with set up, and they can file reports to Facebook about connectivity or retailer issues.

The launch signals Facebook expanding its pursuit of developing world audiences that first need internet access before they can become lucrative Facebook users. Unlike its much-criticized zero-rating program called Free Basics (formerly Internet.org), Express Wi-Fi offers a full, unrestricted version of the web for a price instead of only low-bandwidth services approved by Facebook. This strategy could help it achieve its mission of getting more disconnected people in the developing world online without the net neutrality concerns. Making Express Wi-Fi an actual business might save Facebook from backlash about it masking a user growth driver inside a philanthropic initiative.

Facebook confirmed the launch to TechCrunch, with a spokesperson telling us, “Facebook is releasing the Express Wi-Fi app in the Google Play store to give people another simple and secure way to access fast, affordable internet through their local Express Wi-Fi hotspots.” Sensor Tower first tipped us off to the app.

Weak or expensive connectivity is a huge barrier to Facebook deepening its popularity in the developing world at a time when it’s reaching saturation or even shrinking in some developed world nations. Facebook saw its first user loss ever in the U.S. and Canada region in Q4, with daily active users decreasing by 700,000 in part because of News Feed changes that reduced the presence of engagement-drawing viral videos.

Facebook needs user growth more than ever, and the developing world is where it can find it. That’s why it’s developing advanced technologies like the Aquila solar drone and satellites that can beam down connectivity. It’s also working with telecoms that use microwave towers to beam backhaul bandwidth to its Express Wi-Fi units.

Monetizing the international market has been a big focus for the company. It’s launched new region-specific and low-bandwidth ad units like click-to-missed-call and slideshows. It’s paid off. From 2012 to 2016, average revenue per user grew 4X in the Rest of World region. And that revenue grows even faster when people can load Facebook quickly and cheaply thanks to strong Wi-Fi access. The more accessible Facebook makes this program, the more it could see those internet users turn into social networkers.

Powered by WPeMatico

Ford detailed a bunch of its roadmap for the next few years at a special media event today, and one of the key takeaways is that it’s going all-in on hybrids with its SUV lineup. Ford estimates that SUVs could make up as much as half the entire U.S. industry retail market by 2020, and that’s why it’s shifting $7 billion in investment capital from its cars business over to the SUV segment. By 2020, Ford also aims to have high-performance SUVs in market, including five with hybrid powertrains and one fully battery electric model.

These will include brand new versions of the Ford Escape and Ford Explorer that are coming next year, and two entirely new off-road SUVs, including a new Bronco, and a small SUV that has yet to be named. There’s also that “performance battery electric utility” that will make up part of its overall SUV lineup, which is set for a 2020 release and will spearhead a plan to release six electric vehicle models by 2022.

With this big hybrid push on the SUV side, Ford expects to go from second to first-place in the U.S. hybrid vehicles market by sales, surpassing current leader Toyota by 2021, thanks also to the forthcoming hybrid Mustang and F-150.

Powered by WPeMatico

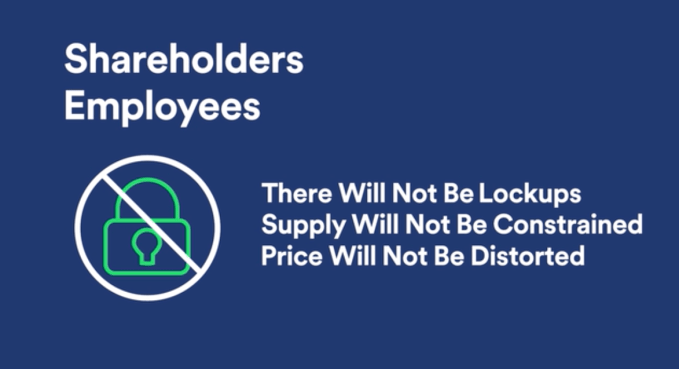

Spotify explained why it’s ditching the traditional IPO for a direct listing on the NYSE on April 3rd today during its Investor Day presentation. With no lockup period and no intermediary bankers, Spotify thinks it can go public without all the typical shenanigans.

Spotify described the rationale for using a direct listing with five points:

Spotify won’t wait for the direct listing, and on March 26th will announce first quarter and 2018 guidance before markets open. It also announced today that there will be no lock-up period, so employees can start selling their shares immediately. This prevents a looming lock-up period expiration that can lead to a dump of shares on the market that sinks the price from spooking investors.

It’s unclear exactly what Spotify will be valued at on April 3rd, but during 2018 its shares have traded on the private markets for between $90 and $132.50, valuing the company at $23.4 billion at the top of the range. The music streaming service now has 159 million monthly active users (up 29 percent in 2017) and 71 million paying subscribers (up 46 percent in 2017.

During CEO Daniel Ek’s presentation, he explained that Spotify emerged as an alternative to piracy by convenience to make paying or ad-supported access easier than stealing. Now he sees the company as the sole leading music streaming service that’s a dedicated music company, subtly throwing shade at Apple, Google, and Amazon. “We’re not focused on selling hardware. We’re not focused on selling books. We’re focused on selling music and connecting artists with fans” said Ek.

Head of R&D Gustav Soderstrom outlined Spotify’s ubiquity strategy, opposed to trying to lock users into a “single platform ecosystem”. He says Spotify does “what’s best for the user and not for the company, and trying to solve the users’ problems by being everywhere.” That’s more shade for Apple, who’s HomePod only works with Apple Music despite customers obviously wishing they could play other streaming services through it.

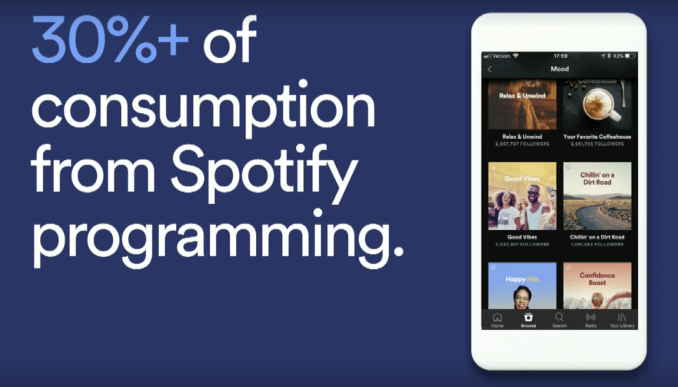

By now being baked into a wide range of third-party hardware through the Spotify Connect program, Soderstrom says Spotify gets a more holistic understanding of its listeners. He declared that Spotify has 5X as much personalization data as its next closest competitor, and that allows it to know what to play you next. He cheekily calls this “self-driving music”.

Spotify CEO Daniel Ek giving the Investor Day presentation

Directing what people listen to turns Spotify into the new top 40 radio — the hit-maker. That gives it leverage over the record labels so Spotify can get better licensing deals and favorable treatment. Now over 30 percent of Spotify listening is based on its own programming through featured playlists, artists, and more.

There’s plenty of room for Spotify to grow. Only 12 percent of the 1.3 billion payment-enabled smartphones in the world have a streaming music subscription and Spotify makes up half of those. And with the free tier, Spotify has the best way to capture people tip-toeing into streaming.

Wall Street loves a two-sided marketplace, so Spotify is positioning itself in the middle of artists and fans, with each side attracting the other. It’s both selling music streaming services to listeners, and selling the tools to reach and monetize those listeners to musicians. That’s both on its platform, and using its targeting and analytics info to deliver efficient ticket and merchandise promotions elsewhere. Ek discussed the flywheel that drives Spotify’s business, explaining that the more people discover music, the more they listen, and the more artists that become successful on the platform, and the more artists will embrace the platform and bring their fans.

Yet with music catalogues and prices mostly similar across the industry, Spotify will have to depend on its personalized recommendations and platform-agnositic strategy to beat its deep pocketed competitors. Music isn’t going away, so whoever can lock in listeners now at the dawn of streaming could keep coining off them for decades. That’s why Spotify not raising cash for marketing through a traditional IPO is a strange choice. But with its focus on playlists and suggestion data, Spotify could build melodic handcuffs for its listeners who wouldn’t dream of starting from scratch on a competitor.

You can follow along with the presentation here.

For more on Spotify’s not-an-IPO, check out our feature piece:

Powered by WPeMatico

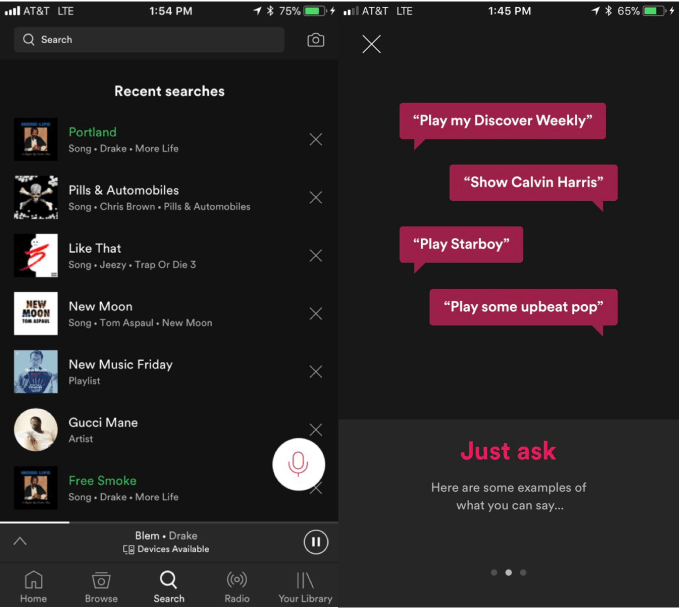

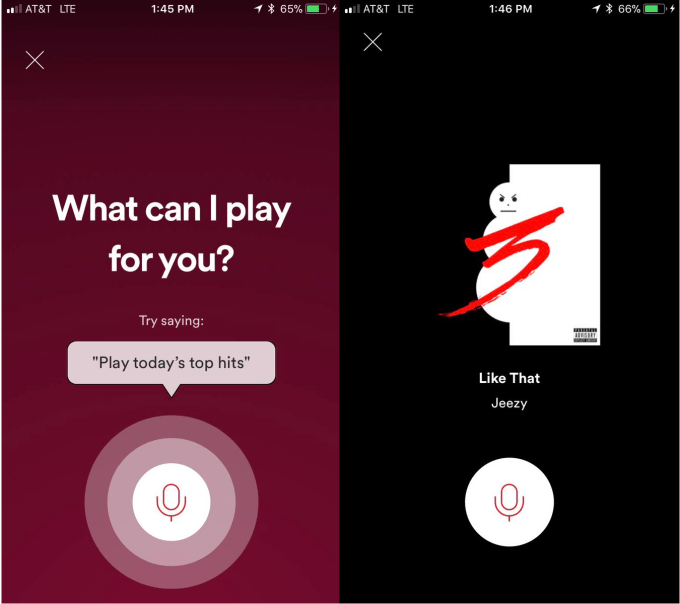

Now Spotify listens to you instead of the other way around. Spotify has a new voice search interface that lets you say “Play my Discover Weekly,” “Show Calvin Harris” or “Play some upbeat pop” to pull up music.

A Spotify spokesperson confirmed to TechCrunch that this is “Just a test for now,” as only a small subset of users have access currently, but the company noted there would be more details to share later. The test was first spotted by Hunter Owens. Thanks to him we have a video demo of the feature below that shows pretty solid speech recognition and the ability to access music several different ways.

Voice control could make Spotify easier to use while on the go using microphone headphones or in the house if you’re not holding your phone. It might also help users paralyzed by the infinite choices posed by the Spotify search box by letting them simply call out a genre or some other category of songs. Spotify briefly tested but never rolled out a very rough design of “driving mode” controls a year ago.

Down the line, Spotify could perhaps develop its own voice interface for smart speakers from other companies or that it potentially builds itself. That would relieve it from depending on Apple’s Siri for HomePod, Google’s Assistant for Home or Amazon’s Alexa for Echo — all of which have accompanying music streaming services that compete with Spotify. Apple chose to make its HomePod speaker Apple Music-only, cutting out Spotify. Its Siri service similarly won’t let people make commands inside third-party apps, so you can ask your iPhone to play a certain song on Apple Music, but not Spotify.

To date, Spotify has only worked with manufacturers to build its Spotify Connect features into boomboxes and home stereos from companies like Bose, rather than creating its own hardware. If it chooses to make Spotify-branded speakers, it might need some of its own voice technology to power them.

Spotify is preparing for a direct listing that will make the company public without a traditional IPO. That means forgoing some of the marketing circus that usually surrounds a company’s debut. That means Spotify may be even more eager to experiment with features or strategies that could be future money-makers so that public investors see growth potential. Breaking into voice directly instead of via its competitors could provide that ‘x-factor.’

For more on Spotify’s not-an-IPO, check out our feature story:

Powered by WPeMatico