TC

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

As companies look for ways to respond to incidents in their complex microservices-driven software stacks, SREs — site reliability engineers — are left to deal with the issues involved in making everything work and keeping the application up and running. Rootly, a new early-stage startup wants to help by building an incident-response solution inside of Slack.

Today the company emerged from stealth with a $3.2 million seed investment. XYZ Venture Capital led the round with participation from 8VC, Y Combinator and several individual tech executives.

Rootly co-founder and CEO Quentin Rousseau says that he cut his SRE teeth working at Instacart. When he joined in 2015, the company was processing hundreds of orders a day, and when he left in 2018 it was processing thousands. It was his job to make sure the app was up and running for shoppers, consumers and stores even as it scaled.

He said that while he was at Instacart, he learned to see patterns in the way people responded to an issue and he had begun working on a side project after he left looking to bring the incident response process under control inside of Slack. He connected with co-founder JJ Tang, who had started at Instacart after Rousseau left in 2018, and the two of them decided to start Rootly to help solve these unique problems that SREs face around incident response.

“Basically we want people to manage and resolve incidents directly in Slack. We don’t want to add another layer of complexity on top of that. We feel like there are already so many tools out there and when things are chaotic and things are on fire, you really want to focus quickly on the resolution part of it. So we’re really trying to be focused on the Slack experience,” Rousseau explained.

The Rootly solution helps SREs connect quickly to their various tools inside Slack, whether that’s Jira or Zendesk or DataDog or PagerDuty, and it compiles an incident report in the background based on the conversation that’s happening inside of Slack around resolving the incident. That will help when the team meets for an incident post-mortem after the issue is resolved.

The company is small at the moment with fewer than 10 employees, but it plans to hire some engineers and sales people over the next year as they put this capital to work.

Tang says that they have built diversity as a core component of the company culture, and it helps that they are working with investor Ross Fubini, managing partner at lead investor XYZ Venture Capital. “That’s also one of the reasons why we picked Ross as our lead investor. [His firm] has probably one of the deepest focuses around [diversity], not only as a fund, but also how they influence their portfolio companies,” he said.

Fubini says there are two main focuses in building diverse companies including building a system to look for diverse pools of talent, and then building an environment to help people from underrepresented groups feel welcome once they are hired.

“One of our early conversations we had with Rootly was how do we both bring a diverse group in and benefit from a diverse set of people, and what’s going to both attract them, and when they come in make them feel like this is a place that they belong,” Fubini explained.

The company is fully remote right now with Rousseau in San Francisco and Tang in Toronto, and the plan is to remain remote whenever offices can fully reopen. It’s worth noting that Rousseau and Tang are members of the current Y Combinator batch.

Powered by WPeMatico

The pandemic has been a time for a lot of reflection on both a personal and business level. Tech companies in particular are assessing whether they will ever again return to a full-time, in-office approach. Some are considering a hybrid approach and some may not go back to a building at all. Amidst all this, Dropbox has decided to reimagine the office with a new concept they are introducing this week called Dropbox Studios.

Dropbox CEO and co-founder Drew Houston sees the pandemic as a forcing event, one that pushes companies to rethink work through a distributed lens. He doesn’t think that many businesses will simply go back to the old way of working. As a result, he wanted his company to rethink the office design with one that did away with cube farms with workers spread across a landscape of cubicles. Instead, he wants to create a new approach that takes into account that people don’t necessarily need a permanent space in the building.

“We’re soft launching or opening our Dropbox Studios [this] week in the U.S., including the one in San Francisco. And we took the opportunity as part of our focus to reimagine the office into a collaborative space that we call a studio,” Houston told me.

Houston says that the company really wanted to think about how to incorporate the best of working at home with the best of working at the office collaborating with colleagues. “We focused on having really great curated in-person experiences, some of which we coordinate at the company level and then some of which you can go into our studios, which have been refitted to support more collaboration,” he said.

Dropbox Studio coffee shop. Image Credits: Dropbox

To that end, they have created a lot of soft spaces with a coffee shop to create a casual feel, conference rooms for teams to have what Houston called “on-site off-sites” and classrooms for organized group learning. The idea is to create purpose-built spaces for what would work best in an office environment and what people have been missing from in-person interactions since they were forced to work at home by the pandemic, while letting people accomplish more individual work at home.

The company is planning on dedicated studios in major cities like San Francisco, Seattle, Tokyo and Tel Aviv with smaller on-demand spaces operated by partners like WeWork in other locations.

Dropbox Studio classroom space. Image Credits: Dropbox

As Houston said when he appeared at TechCrunch Disrupt last year, his company sees this as an opportunity to be on the forefront of distributed work and act as an example and a guide to help other companies as they undertake similar journeys.

“When you think more broadly about the effects of the shift to distributed work, it will be felt well beyond when we go back to the office. So we’ve gone through a one-way door. This is maybe one of the biggest changes to knowledge work since that term was invented in 1959,” Houston said last year.

He recognizes that they have to evaluate how this is going to work and iterate on the design as needed, just as the company iterates on its products and they will be evaluating the new spaces and the impact on collaborative work and making adjustments when needed. To help others, Dropbox is releasing an open-source project plan called the Virtual First Toolkit.

The company is going all-in with this approach and will be subletting much of its existing office space as it moves to this new way of working and its space requirements change dramatically. It’s a bold step, but one that Houston believes his company is uniquely positioned to undertake, and he wants Dropbox to be an example to others on how to reinvent the way we work.

Powered by WPeMatico

When the Pentagon killed the JEDI cloud program yesterday, it was the end of a long and bitter road for a project that never seemed to have a chance. The question is why it didn’t work out in the end, and ultimately I think you can blame the DoD’s stubborn adherence to a single vendor requirement, a condition that never made sense to anyone, even the vendor that ostensibly won the deal.

In March 2018, the Pentagon announced a mega $10 billion, decade-long cloud contract to build the next generation of cloud infrastructure for the Department of Defense. It was dubbed JEDI, which aside from the Star Wars reference, was short for Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure.

The idea was a 10-year contract with a single vendor that started with an initial two-year option. If all was going well, a five-year option would kick in and finally a three-year option would close things out with earnings of $1 billion a year.

While the total value of the contract had it been completed was quite large, a billion a year for companies the size of Amazon, Oracle or Microsoft is not a ton of money in the scheme of things. It was more about the prestige of winning such a high-profile contract and what it would mean for sales bragging rights. After all, if you passed muster with the DoD, you could probably handle just about anyone’s sensitive data, right?

Regardless, the idea of a single-vendor contract went against conventional wisdom that the cloud gives you the option of working with the best-in-class vendors. Microsoft, the eventual winner of the ill-fated deal acknowledged that the single vendor approach was flawed in an interview in April 2018:

Leigh Madden, who heads up Microsoft’s defense effort, says he believes Microsoft can win such a contract, but it isn’t necessarily the best approach for the DoD. “If the DoD goes with a single award path, we are in it to win, but having said that, it’s counter to what we are seeing across the globe where 80% of customers are adopting a multicloud solution,” Madden told TechCrunch.

Perhaps it was doomed from the start because of that. Yet even before the requirements were fully known there were complaints that it would favor Amazon, the market share leader in the cloud infrastructure market. Oracle was particularly vocal, taking its complaints directly to the former president before the RFP was even published. It would later file a complaint with the Government Accountability Office and file a couple of lawsuits alleging that the entire process was unfair and designed to favor Amazon. It lost every time — and of course, Amazon wasn’t ultimately the winner.

While there was a lot of drama along the way, in April 2019 the Pentagon named two finalists, and it was probably not too surprising that they were the two cloud infrastructure market leaders: Microsoft and Amazon. Game on.

The former president interjected himself directly in the process in August that year, when he ordered the Defense Secretary to review the matter over concerns that the process favored Amazon, a complaint which to that point had been refuted several times over by the DoD, the Government Accountability Office and the courts. To further complicate matters, a book by former defense secretary Jim Mattis claimed the president told him to “screw Amazon out of the $10 billion contract.” His goal appeared to be to get back at Bezos, who also owns the Washington Post newspaper.

In spite of all these claims that the process favored Amazon, when the winner was finally announced in October 2019, late on a Friday afternoon no less, the winner was not in fact Amazon. Instead, Microsoft won the deal, or at least it seemed that way. It wouldn’t be long before Amazon would dispute the decision in court.

By the time AWS re:Invent hit a couple of months after the announcement, former AWS CEO Andy Jassy was already pushing the idea that the president had unduly influenced the process.

“I think that we ended up with a situation where there was political interference. When you have a sitting president, who has shared openly his disdain for a company, and the leader of that company, it makes it really difficult for government agencies, including the DoD, to make objective decisions without fear of reprisal,” Jassy said at that time.

Then came the litigation. In November the company indicated it would be challenging the decision to choose Microsoft charging that it was was driven by politics and not technical merit. In January 2020, Amazon filed a request with the court that the project should stop until the legal challenges were settled. In February, a federal judge agreed with Amazon and stopped the project. It would never restart.

In April the DoD completed its own internal investigation of the contract procurement process and found no wrongdoing. As I wrote at the time:

While controversy has dogged the $10-billion, decade-long JEDI contract since its earliest days, a report by the DoD’s inspector general’s office concluded today that, while there were some funky bits and potential conflicts, overall the contract procurement process was fair and legal and the president did not unduly influence the process in spite of public comments.

Last September the DoD completed a review of the selection process and it once again concluded that Microsoft was the winner, but it didn’t really matter as the litigation was still in motion and the project remained stalled.

The legal wrangling continued into this year, and yesterday the Pentagon finally pulled the plug on the project once and for all, saying it was time to move on as times have changed since 2018 when it announced its vision for JEDI.

The DoD finally came to the conclusion that a single-vendor approach wasn’t the best way to go, and not because it could never get the project off the ground, but because it makes more sense from a technology and business perspective to work with multiple vendors and not get locked into any particular one.

“JEDI was developed at a time when the Department’s needs were different and both the CSPs’ (cloud service providers) technology and our cloud conversancy was less mature. In light of new initiatives like JADC2 (the Pentagon’s initiative to build a network of connected sensors) and AI and Data Acceleration (ADA), the evolution of the cloud ecosystem within DoD, and changes in user requirements to leverage multiple cloud environments to execute mission, our landscape has advanced and a new way ahead is warranted to achieve dominance in both traditional and nontraditional warfighting domains,” said John Sherman, acting DoD chief information officer in a statement.

In other words, the DoD would benefit more from adopting a multicloud, multivendor approach like pretty much the rest of the world. That said, the department also indicated it would limit the vendor selection to Microsoft and Amazon.

“The Department intends to seek proposals from a limited number of sources, namely the Microsoft Corporation (Microsoft) and Amazon Web Services (AWS), as available market research indicates that these two vendors are the only Cloud Service Providers (CSPs) capable of meeting the Department’s requirements,” the department said in a statement.

That’s not going to sit well with Google, Oracle or IBM, but the department further indicated it would continue to monitor the market to see if other CSPs had the chops to handle their requirements in the future.

In the end, the single vendor requirement contributed greatly to an overly competitive and politically charged atmosphere that resulted in the project never coming to fruition. Now the DoD has to play technology catch-up, having lost three years to the histrionics of the entire JEDI procurement process and that could be the most lamentable part of this long, sordid technology tale.

Powered by WPeMatico

Opaque, a new startup born out of Berkeley’s RISELab, announced a $9.5 million seed round today to build a solution to access and work with sensitive data in the cloud in a secure way, even with multiple organizations involved. Intel Capital led today’s investment with participation by Race Capital, The House Fund and FactoryHQ.

The company helps customers work with secure data in the cloud while making sure the data they are working on is not being exposed to cloud providers, other research participants or anyone else, says company president Raluca Ada Popa.

“What we do is we use this very exciting hardware mechanism called Enclave, which [operates] deep down in the processor — it’s a physical black box — and only gets decrypted there. […] So even if somebody has administrative privileges in the cloud, they can only see encrypted data,” she explained.

Company co-founder Ion Stoica, who was a co-founder at Databricks, says the startup’s solution helps resolve two conflicting trends. On one hand, businesses increasingly want to make use of data, but at the same time are seeing a growing trend toward privacy. Opaque is designed to resolve this by giving customers access to their data in a safe and fully encrypted way.

The company describes the solution as “a novel combination of two key technologies layered on top of state-of-the-art cloud security—secure hardware enclaves and cryptographic fortification.” This enables customers to work with data — for example to build machine learning models — without exposing the data to others, yet while generating meaningful results.

Popa says this could be helpful for hospitals working together on cancer research, who want to find better treatment options without exposing a given hospital’s patient data to other hospitals, or banks looking for money laundering without exposing customer data to other banks, as a couple of examples.

Investors were likely attracted to the pedigree of Popa, a computer security and applied crypto professor at UC Berkeley and Stoica, who is also a Berkeley professor and co-founded Databricks. Both helped found RISELabs at Berkeley where they developed the solution and spun it out as a company.

Mark Rostick, vice president and senior managing director at lead investor Intel Capital says his firm has been working with the founders since the startup’s earliest days, recognizing the potential of this solution to help companies find complex solutions even when there are multiple organizations involved sharing sensitive data.

“Enterprises struggle to find value in data across silos due to confidentiality and other concerns. Confidential computing unlocks the full potential of data by allowing organizations to extract insights from sensitive data while also seamlessly moving data to the cloud without compromising security or privacy,” Rostick said in a statement

He added, “Opaque bridges the gap between data security and cloud scale and economics, thus enabling inter-organizational and intra-organizational collaboration.”

Powered by WPeMatico

The numbers don’t lie.

According to DocSend, the average pitch deck is reviewed for just three minutes. And if you think a senior VC is studying the presentation your team crafted for months as if it were a Fabergé egg — well, you might be disappointed.

Even if you are lucky enough to land a meeting, it’s more likely that a junior person went through your pitch and ran it up the chain.

“The biggest lie in venture capital is: ‘Yes, I read through your deck,’” says Evan Fisher, founder of Unicorn Capital and Minimal Capital.

“Because those words are immediately followed by, ‘ … but why don’t you run us through it from the beginning?’”

Full Extra Crunch articles are only available to members.

Use discount code ECFriday to save 20% off a one- or two-year subscription.

According to Fisher, the pro forma pitch deck is a thing of the past. Instead, the founders he’s worked with who made video pitches netted two to five times as many investor meetings as people who sent traditional pitch decks.

They also received up to five times more in terms of investor commitments from the first 20 meetings.

“Even if the only benefit was that other investment committee members heard the story direct from the founder, that alone would make your video pitch worth it,” says Fisher.

Thanks very much for reading Extra Crunch this week!

Walter Thompson

Senior Editor, TechCrunch

@yourprotagonist

Image Credits: TechCrunch

In an exclusive interview with Hardware Editor Brian Heater, Nothing Founder Carl Pei discussed the product and design principles underpinning Ear (1), a set of US$99/€99/£99 wireless earbuds that will hit the market later this month.

“We’re starting with smart devices,” said Pei. “Ear (1) is our is our first device. I think it has good potential to gain some traction.”

Despite Apple’s market share and the number of players already competing in the space, “we’ve just focused on being ourselves,” said Nothing’s founder, who also shared initial marketing plans and discussed the inherent tensions involved with manufacturing consumer hardware.

“Everything is a trade-off. Like if you pursue this design, that has a ton of implications. Battery life has ton of implications on size and on cost. The materials you use have implications on cost. Everything has an implication on timeline. It’s like 4D chess in terms of trade-offs.”

Image Credits: Nigel Sussman (opens in a new window)

Last week, just days after its U.S. IPO, cybersecurity regulators in China banned ride-hailing company Didi from onboarding new members.

Over the weekend, authorities called for Didi to be removed from several app stores due to “serious violations of laws and regulations in collecting and using personal information.”

The move suggests that China’s government “is willing to sacrifice business results for control,” writes Alex Wilhelm in this morning’s edition of The Exchange.

“For China-based companies hoping to list in the United States, the market likely just got much, much colder.”

Image Credits: Peter Dazeley (opens in a new window)/ Getty Images

Jasper Kuria, the managing partner of CRO consultancy The Conversion Wizards, walks through an A/B test showing how research-driven CRO (conversion rate optimization) techniques led to a 79% increase in conversion rates for China Expat Health, a lead-generation company.

“Using research-based CRO principles to optimize a landing page for PPC (pay per click) traffic produced a 79% conversion lift, dramatically reducing the cost per lead for the company,” Kuria writes.

“They could then afford to bid more per click, which increased their overall monthly leads. CRO can have this kind of transformative effect on your business.”

Powered by WPeMatico

While SaaS has become the default way to deliver software in 2021, it still takes a keen eye to find the companies that will grow into successful businesses, maybe even more so with so much competition. That’s why we’re bringing together three investors to discuss what they look for when they invest in SaaS startups.

For starters, we’ll have Sarah Guo, who has been a partner at Greylock since 2013 where she concentrates on AI, cybersecurity, infrastructure and the future of work — all in a SaaS context of course. Among her investments are Obsidian, Clubhouse and Awake. Her exits include Demisto, which Palo Alto acquired for $560 million in 2019 and Skyhigh Networks, which McAfee bought for $400 million in 2018.

Prior to joining Greylock, she worked for Goldman Sachs investing in growth-stage companies and advising SaaS companies like Dropbox and Workday.

Next we’ll have Kobie Fuller, a partner at Upfront Ventures, who looks at SaaS as well as AR and VR. Fuller has been at Upfront since 2016 when he joined after a three-year stint at Accel. He oversaw a pair of billion dollar exits while at Accel including ExactTarget to Salesforce for $2.5 billion and Oculus to Facebook for $2 billion. Upfront investments include Bevy, community building software, which recently got a $40 million investment with 20% of that coming from 25 Black investors.

Finally, we’ll have Casey Aylward, a principal at Costanoa Ventures where she concentrates on early-stage enterprise startups. Among her investments have been Aserto, Bigeye and Cyral. She tends to concentrate on developer tools. “My entire career so far has been focused on developers: whether it was building tools for developers, building software myself or now investing in enabling technologies for the next generation of technical users,” she wrote on her bio page.

This prestigious group will share their thoughts at TC Sessions: SaaS, a one-day virtual event that will examine the state of SaaS to help startup founders, developers and investors understand the state of play and what’s next. We hope you’ll join us.

The single-day event will take place 100% virtually on October 27 and will feature actionable advice, Q&A with some of SaaS’s biggest names and plenty of networking opportunities. Importantly, $75 Early Bird passes are now on sale. Book your passes today to save $100 before prices go up.

Powered by WPeMatico

Having a unique product used to give you at least a few months of lead time over other players, but that advantage seems to matter less and less — just think of how Twitter Spaces managed to land on Android ahead of Clubhouse.

In this context, how do you stay ahead of your competition when you know it’s only a matter of time before they copy your best features?

The solution is messaging, says conversion optimization expert Peep Laja. Unlike features that can be copied and commoditized, a strategic narrative can be a long-term advantage. In the interview below, he explains why and how startups should work on this from their very early days.

(TechCrunch is asking founders who have worked with growth marketers to share a recommendation in this survey. We’ll use your answers to find more experts to interview.)

Laja is the founder of several marketing and optimization businesses: CXL, Speero and Wynter. In a recent Twitter thread, he highlighted common stories and narratives that startups can use, such as “challenging the way things have always been done” or “irreverence,” and came up with examples of companies that employ these tactics. We asked him to expand on some of his thoughts and recommendations for startup founders.

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Your site’s tagline tells startups that “product-based differentiation is going away” and that they should “win on messaging.” Can you explain the rationale behind this?

David Cancel, the CEO of Drift, said that famously in 2017.

Broadly speaking, any startup is competing on innovation or messaging, and, ideally, on both. Usually, you want to start with innovation — do something new or something better. However, competing on features is a transient advantage. Doing what no one else is doing won’t last: Sooner or later, you’ll get copied by big players or other startups, so innovation is not enough. Features are a transient advantage that lasts maybe two years, but rarely more. Meanwhile, having the right narrative and messaging can give you a long-lasting advantage.

Startups competing on story have a big advantage if they are bold because big companies optimize for being safe, and that often means being very boring, but nobody will call them out for it. In contrast, startups can be brave and polarizing on purpose.

Ideally, you start with innovation, and at the same time start building your brand as well. Once the competition achieves feature parity, you make people choose you because of the brand. It’s hard to be sustainably objectively better than others, but you definitely cannot be objectively worse.

You help startups do research to find and validate their strategic narrative. Can you explain this concept?

As startups get bigger, they realize that they need to communicate less on features and more on story. Their narrative needs to be connected to a bigger concept and be a strategic narrative. “The world used to be like this, but it changed, and our startup will help you in this new context.”

A fictional example would be selling a course of AI for marketers; ideally, instead of talking about AI, you’d lead with a story, explaining that AI and machine learning are an unstoppable thing that is going to change everything. The future is already here, but not evenly distributed yet. There is no stopping this train. You can get on it, or get left behind. Companies that adopt AI will overtake others, and marketers need to learn AI to adapt. This would make the product way more attractive … than selling it through features: “AI for marketers course. Seven hours of video. Top lecturers.”

This is also what I am doing with my company, Wynter. If you look at SaaS, there are 53 times more companies than 10 years ago, with hundreds of tools available in any given category — think of email marketing, for instance. And a striking thing about competitors in each category is sameness: They pretty much offer the same features. In other words, differentiation based on features doesn’t work anymore. Most companies also look the same and say the same things. Sameness is the default for most companies today. Sameness is the combined effect of companies being too similar in their offers, poorly differentiated in their branding, and indistinct in their communication. You’d think that companies would be all about differentiation these days. Curiously, the opposite is true.

Given that feature-based differentiation is a fleeting advantage, companies should compete on brand. That’s the new world we are in, and in order to win, you need to know what your audience wants and how what you’re telling your audience is landing on them. … This is what my company does, and that’s how I pitch it. As you can see, it follows the narrative I described earlier: showing how the world has changed, and explaining that what used to work is no longer adapted to the new reality that is starting to emerge.

How would you recommend founders anchor their startup to success cases?

Bring your best proof that the world has changed — with data to back you up — and then make a case that winning requires a new strategy. Then show winners and losers based on the strategy they have been using, and use it as new proof that it is best suited for this new world. For instance, if you are pitching product-led growth, you can give examples showing that it is working as a go-to-market strategy because we live in a new world where customers want to start using the product right away. You can give examples showing how this is working, and tie your startup to them.

For other examples, you could also look at what HubSpot CTO Dharmesh Shah does with community-led growth.

There’s also this startup shipping hardware to remote workers, Firstbase. The Twitter timeline of its CEO, Chris Herd, is a good example of what I am saying: Just look at how he is selling the narrative, not his company.

So first and foremost you sell a narrative, a point of view on the world. And only much later you explain how your company helps their customer win using this new strategy. The narrative is the context for the features, etc.

How can startups avoid getting it wrong?

Your narrative can miss the mark if it’s not about change in the external world and only internal to the company, or if you are investing in a change that is not happening that you are failing to make sound credible. To win on brand, you need to measure the effectiveness of your narrative.

How do you test that? If you do direct sales, getting feedback is pretty straightforward. In my sales demo, I talk about the narrative before going into the demo. If people ask for a copy of my deck, I know it’s hitting home. I also ask for feedback, observe if people are nodding, etc. If you are not going through this sales process — for instance, if you are doing product-led growth — you need to do message testing. This can be one-on-one or as a qualitative survey, but either way, you need to make sure that you are testing on your actual target audience.

We do that at Wynter — you can conduct message testing as well as for customer research, so you can survey people not just on your message, but also on their perception of the world. This helps you discover what in your sales pitch on your website is hitting home, what falls flat, how it compares to the competition and so on.

Have you worked with a talented individual or agency who helped you find and keep more users?

Respond to our survey and help us find the best startup growth marketers!

When should startups start working on their messaging?

Companies should attach themselves to a narrative from day one because innovation is transient. Staying ahead of your competition through innovation forever is very rare. Winning on brand is more accessible. So before you have product-market fit, you need message-market fit. Potential customers will look at this. It can even be a moat: Instead of positioning yourself as a commodity (when you sell yourself through non-innovative features, you’re a commodity), you develop a story that people emotionally connect to. You’ll know it’s a moat if it makes it possible for you to charge more than your competitors. This doesn’t happen with a feature: It eventually becomes commoditized and expected. This is much less of a problem when you have a brand.

How should the narrative evolve over time, if at all?

Your narrative also needs to evolve as the world evolves; you always need to be scanning for what’s happening and the broader context. The rise of remote is an example of that; see, for instance, how HR company Lattice attached itself to it as it expanded from one feature to a broader offering.

This connects to a broader point, which is that we are going from mass market to smaller clusters. For example, we all used to watch the same shows, versus all the niche content that has emerged today. This can be good for startups because in most cases, they wouldn’t be able to afford to aim for mass-market appeal from the start anyway. But as they grow, their narrative may have to evolve. And there can also be a brand narrative and a strategic narrative at the same time, with the latter being the one that evolves over time.

In terms of stories, some of the ones I mentioned in my Twitter thread are more timeless, but even some of these might not work forever. For instance, the “David versus Goliath” story might not sound authentic once you reach a certain stage. I also gave the example of Wise “standing up for the people” and focusing on disrupting bank fees, but now that it is getting disrupted itself, it might have to change its narrative. Some companies don’t need to move away from their original narrative, but some do.

Powered by WPeMatico

The SPAC parade continues in this shortened week with news that community social network Nextdoor will go public via a blank-check company. The unicorn will merge with Khosla Ventures Acquisition Co. II, taking itself public and raising capital at the same time.

Per the former startup, the transaction with the Khosla-affiliated SPAC will generate gross proceeds of around $686 million, inclusive of a $270 million private investment in public equity, or PIPE, which is being funded by a collection of capital pools, some prior Nextdoor investors (including Tiger), Nextdoor CEO Sarah Friar and Khosla Ventures itself.

Notably, Khosla is not a listed investor in the company per Crunchbase or PitchBook, indicating that even SPACs formed by venture capital firms can hunt for deals outside their parent’s portfolio.

Per a Nextdoor release, the transaction will value the company at a “pro forma equity [valuation] of approximately $4.3 billion.” That’s a great price for the firm that was most recently valued at $2.17 billion in a late 2019-era Series H worth $170 million, per PitchBook data. Those funds were invested at a flat $2 billion pre-money valuation.

So, what will public investors get the chance to buy into at the new, higher price? To answer that we’ll have to turn to the company’s SPAC investor deck.

Our general observations are that while Nextdoor’s SPAC deck does have some regular annoyances, it offers a clear-eyed look at the company’s financial performance both in historical terms and in terms of what it might accomplish in the future. Our usual mockery of SPAC charts mostly doesn’t apply. Let’s begin.

We’ll proceed through the deck in its original slide order to better understand the company’s argument for its value today, as well as its future worth.

The company kicks off with a note that it has 27 million weekly active users (neighbors, in its own parlance), and claims users in around one in three U.S. households. The argument, then, is that Nextdoor has scale.

A few slides later, Nextdoor details its mission: “To cultivate a kinder world where everyone has a neighborhood they can rely on.” While accounts like @BestOfNextdoor might make this mission statement as coherent as ExxonMobil saying that its core purpose was, say, atmospheric carbon reduction, we have to take it seriously. The company wants to bring people together. It can’t control what they do from there, as we’ve all seen. But the fact that rude people on Nextdoor is a meme stems from the same scale that the company was just crowing about.

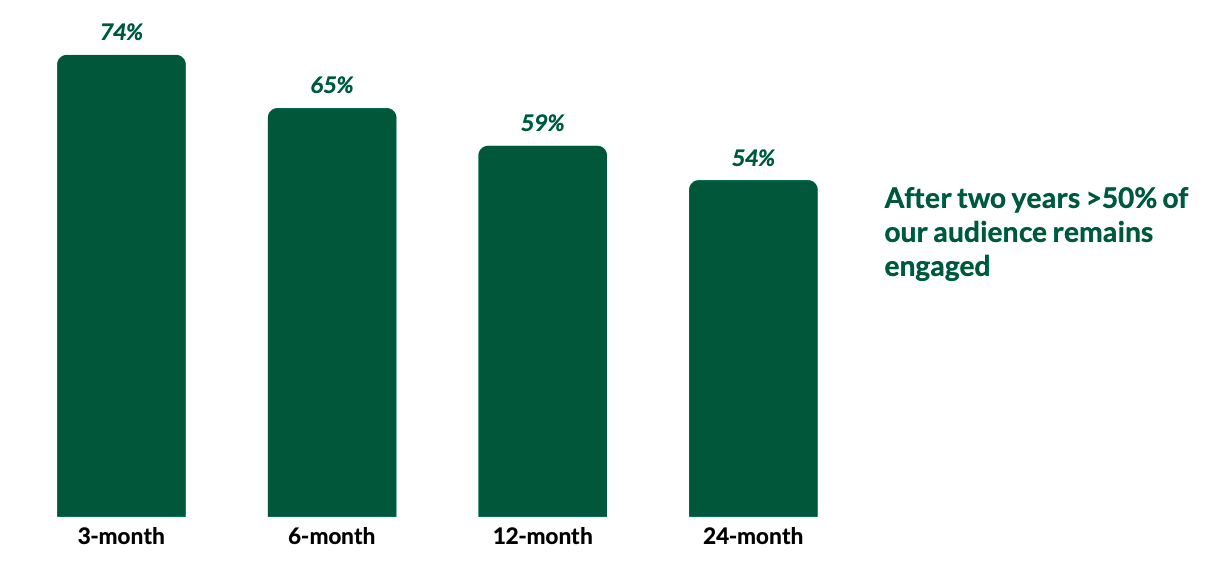

Underscoring its active user counts are Nextdoor’s retention figures. Here’s how it describes that metric:

Image Credits: Nextdoor SPAC investor deck

These are monthly active users, mind, not weekly active, the figure that the company cited up top. So, the metrics are looser here. And the company is counting users as active if they have “started a session or opened a content email over the trailing 30 days.” How conservative is that metric? We’ll leave that for you to decide.

The company’s argument for its value continues in the following slide, with Nextdoor noting that users become more active as more people use the service in a neighborhood. This feels obvious, though it is nice, we suppose, to see the company codify our expectations in data.

Nextdoor then argues that its user base is distinct from that of other social networks and that its users are about as active as those on Twitter, albeit less active than on the major U.S. social networks (Facebook, Snap, Instagram).

Why go through the exercise of sorting Nextdoor into a cabal of social networks? Well, here’s why:

Powered by WPeMatico

There’s a lot wrapped up in a name: feelings, emotions, connotation, unconscious bias, personal history. It’s an identity — it gives something meaning and importance.

In leading marketing and brand at High Alpha, I think about naming quite a bit. As a venture studio, we co-found and launch five to 10 new software startups every year. It is my team’s responsibility to create and build out the brands for all the new companies we start, including everything from naming and domain acquisition to brand identity and websites. Over the past five years, we’ve named more than 30 software startups at High Alpha.

Over the past five years, we’ve named more than 30 software startups.

As a soon-to-be first-time parent, the idea of naming has taken on a whole new meaning and importance in my life. Even though I help name new companies for a living, I now fully understand the paralysis that often comes when faced with the task of deciding the name for someone or something that’s especially important to you.

Because of this, I’ve always tried to take an objective, pragmatic approach to naming a company with our CEOs and other startups. Naming is an incredibly difficult and nuanced process. It’s fraught with subjectiveness and personal preference. And to top it all off, most founders have zero (or very little) experience in naming.

The truth is that business names fall on a bell curve — you have a small number of outliers that actively contribute to your success and a small number of outliers that actively impair your ability to succeed. The vast majority, though, fall somewhere in the middle in their impact on your business.

So, how should a founder go about effectively naming their baby startup and not picking a name that will hurt them? I’m sharing my own criteria and lessons for how to go about naming your startup, how to evaluate a company name and what makes for a good company name.

As a founder, one of the first criteria to look at is ownability and URL availability. Nowadays, you’ll be hard-pressed to find a name where the .com is still available. I oftentimes will look at .io, .co, get_______.com, or _____hq.com as my top alternatives to a .com, but I always still prefer if the .com is potentially attainable in the future. It may be parked by a domain investor or someone asking a ridiculous price, but that’s always better than an established business using your .com. If not, you will always be fighting a search battle with some other brand that owns your .com.

This goes much further than just the availability of the coveted .com domain, though. You should evaluate the competitiveness and search congestion around your branded keywords. A company named “Apple” or “Lumber” is going to have a really hard time competing for search placements, even if they don’t sell computers or building supplies. An established name and word is also going to come with existing connotations and previous experiences in your audience’s mind. You want a name free from as much baggage as possible so you can easily build your own connotations and memories.

Powered by WPeMatico

Part of the complex process that turns raw materials into finished products like detergents, cosmetics and flavors relies on enzymes, which facilitate chemical transformations. But finding the right enzyme for a new or proposed drug or additive is a drawn out and almost random process — which Allozymes aims to change with a remarkable new system that could set a new standard in the industry, and has raised a $5 million seed round to commercialize.

Enzymes are chains of amino acids, the “building blocks of life” among the many things encoded in DNA. These large, complex molecules bind to other substances in a way that facilitates a chemical reaction, say turning sugars in a cell into a more usable form of energy.

One also finds enzymes in the world of manufacturing, where major companies have identified and isolated enzymes that perform valuable work like taking some cheap base ingredients and making them combine into a more useful form. Any company that sells or needs lots of any particular chemical that doesn’t appear abundantly in nature probably has enzymatic processes to aid in creating more of it.

But it’s not like there’s just an enzyme for everything. When you’re inventing new molecules from scratch, like a novel drug or flavoring, there’s no reason why there should be a naturally occurring enzyme that reacts with or creates it. No animal synthesizes allergy medicine in its cells, so companies must find or create new enzymes that do what’s needed. The problem is that enzymes are generally at least 100 units long, and there are 20 amino acids to choose from, meaning for even the simplest novel enzyme you’re looking at uncountably numerous variations.

By starting with known enzymes and systematically working through variations that seem intuitively like they might work, researchers have been able to find new and useful enzymes, but the process is complex and slow even when fully automated: at most a couple hundred a day, and that’s if you happen to have a top-of-the-line robotic lab.

So when Allozymes comes in with a claim that it can screen up to ten million per day, you can imagine the level of change that represents.

Allozymes was founded by Peyman Salehian (CEO) and Akbar Vahidi (CTO), two Iranian chemical engineers who met while pursuing their PhDs at the National University of Singapore. The three years of research leading up to the commercial product also occurred at NUS, which holds the patent and exclusively licenses it to the company.

“The state of the art hasn’t changed in 20 years,” said Salehian. “When we talk with big pharma, they have whole departments for this, they have $2 million robots, and it still takes a year to get a new enzyme.”

The Allozymes platform will speed up the process by several orders of magnitude, while decreasing the cost by an order of magnitude, Salehian said. If these estimates bear out, it effectively trivializes the enzyme search and obsoletes billions in investments and infrastructure. Why pay more to get less?

Traditionally, enzymes are isolated and selected over a multi-step process that involves introducing DNA templates into cells, which are cultured to create the target enzymes, which once a certain growth state is achieved, are analyzed robotically. If there are promising results, you go down that road with more variations, otherwise you start again from the beginning. There’s a lot of picking and placing little dishes, waiting for enough cells to produce enough of the stuff, and so on.

The process, designed by Vahidi and other researchers at NUS, is fully contained with a benchtop device, and generates almost no waste. Instead of using culture dishes, the device puts the necessary cells, substrate, and other ingredients in a tiny droplet in a microfluidic system. The reactions occur inside this little drop, which is incubated, tracked, and eventually collected and tested in a fraction of the time a larger sample would take.

Allozymes isn’t selling the device, though. It’s enzyme engineering as a service, and for now their partners and customers seem content with that. Its primary service is cut-to-size, depending on the needs of the project. For instance, maybe a company has a working enzyme already and just wants a variant that’s easier to synthesize or less dependent on certain expensive additives. With a solid starting point and flexible goal that might be a project on the smaller side. Another company may be looking to completely replace hard chemistry processes in their manufacturing, know the start and the end of the process but need an enzyme to fill in the gaps; that might be a more wide ranging and expensive project.

Vahidi explained that the goal is not to “democratize” enzyme engineering. It’s still expensive and large-scale enough that it will primarily be done by large companies, but now they can get a hundred thousand times more out of their R&D dollar. The speed and value put them above the competition, said Salehian, with companies like Codexis, Arzeda, and Ginkgo Bioworks also doing enzyme bioengineering but at lower rates and with different priorities.

Occasionally the company might strike a bargain to take part ownership of an IP or product, but that’s not really the business model, Salehian said. Some early work consisted of actually making the final compound, but ultimately the core product is expected to be the service. (Still, a million-dollar order is nothing to sneeze at.)

It may have occurred to you that in the process of doing a job, Allozymes might sort through hundreds of millions of enzymes. Rest assured, they are well aware of the value these may represent. The service transitions seamlessly into the inevitable data play.

“If you have a big data set that shows ‘if you change this amino acid this will be the function,’ you don’t even need to engineer it, you can eliminate it [i.e. from consideration]. You can even design enzymes if you know enough,” Salehian said.

The company’s recent $5 million seed round was led by Xora Innovation (from Temasek, Singapore’s sovereign fund), with participation from SOSV’s HAX, Entrepreneur First and TI Platform Management. Salehian explained that they planned to incorporate in the U.S. following interest from American venture firms, but Temasek’s early-stage investor convinced them to stay.

“Biotransformation is in huge demand on this side of the world,” Salehian said. “Chemical, agriculture, and food companies need to do it, but no platform company can deliver these services. So we tried to fill that gap.”

Powered by WPeMatico