TC

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

With most popular online video games, there’s a huge gap between being a good player and a great one. A casual player might be able to hold their own against other casual players, only for a random pro to wander by and chew through everyone like they’re somehow playing with a different set of rules.

Could an AI-driven voice in your ear help close that gap, if only a bit? SenpAI.GG, a company out of Y Combinator’s latest batch, thinks so.

Much of that aforementioned gap boils down to practice, muscle memory and — let’s face it — natural ability. But as a game gets older/bigger/more complex, the best players tend to have a wealth of one resource that’s oh-so-crucial, if not oh-so-fun to gather: information.

Which guns do the most damage at this range? Which character is best suited to counter that character on this map? Hell, what changed in that “minor update” that flashed across your screen as you were booting up the game? Wait, why is my favorite weapon suddenly so much harder to control?

Staying on top of all this information as players discover new tactics and updates shift the “meta” is a challenge in its own right. It usually involves lots of Twitch streams, lots of digging around Reddit threads and lots of poring over patch notes.

SenpAI.GG is looking to surface more of that information automatically and help new players get good, faster. Their desktop client presents you with information it thinks can help, post-game analysis on your strategies, plus in-game audio cues for the things you might not be great at tracking yet.

It currently supports a handful of games — League of Legends, Valorant and Teamfight Tactics — with the info it provides varying from game to game. In LoL, for example, it’ll look at both teams’ selected champions and try to recommend the one you could pick to help most; in Valorant, meanwhile, it can give you an audio heads-up that one of your teammates is running low on health (before said teammate starts yelling at you to heal them), when you’ve forgotten to reload or how long you’ve got before the Spike (read: game-ending bomb) explodes.

SenpAI.GG’s in-game overlay providing League of Legends insights. Image Credits: SenpAI.GG

Just as important as the information it provides is the information it won’t provide. In my chat with him, SenpAI.GG founder Olcay Yilmazcoban seemed very aware that there’s a hard-to-define line here where “assistant” blurs into “cheating tool” — but the company follows certain rules to stay on the right side of things and prevent their players from getting banned.

They won’t, for example, ever take action on a player’s behalf — they might fire an audio cue to say “hey, you should heal that teammate,” but they won’t press the button for you. They’ll only generate their real-time insights from what’s on your screen — not anything hidden within the running process. They also won’t do things like reveal an enemy’s location just because your teammate is also running the app and can see them. Think “good player standing over your shoulder,” not “wall hack.” The company says that they’re always within each game developer’s competitive fairness guidelines, and only work with approved/provided APIs.

It’s a good idea because it’s one that, arguably, never gets old. With each new game they support, they’ve got a new potential audience to serve. Meanwhile, it’s not as if the old games/insights will expire — a game’s big ol’ book-of-stuff-you-need-to-know tends to only get bigger and more complex as a game ages and the patches pile up. There are games I’ve been playing for years where I’d still love a voice assistant that says “Oh hey, the recoil on the gun you just picked up has gotten way more intense since the last time you played.” SenpAI.GG isn’t there yet, but there’s a ton of natural room for growth.

Yilmazcoban tells me that they currently have over 400,000 active users, with a team of 11 people working on it. The base app is free, with plans to offer advanced features for a couple bucks a month.

Powered by WPeMatico

Ward van Gasteren embraces the “growth hacker” term, despite the fact that some in the profession prefer the term “growth marketing” or simply “growth.” What’s the difference to him? The hacking part should be a distinct effort on top of ongoing marketing, he says.

“Growth hacking is great to kickstart growth, test new opportunities and see what tactics work,” he tells us. “Marketeers should be there to continue where the growth hackers left off: build out those strategies, maintain customer engagement and keep tactics fresh and relevant.”

Based in The Netherlands, he has developed his own growth hacking courses, Grow With Ward, and worked with large companies like TikTok, Pepsi and Cisco, and startups like Cyclemasters, Somnox and Zigzag. In the conversation below, van Gasteren shares the importance of building internal processes around growth for the long term, the state of growth today and his own development.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You’re a certified growth hacker — how do you think this sets you apart from others? How has this certification changed the way you approach working with clients?

I was part of the first-ever class from Growth Tribe (when they still offered multimonth traineeships), which was an amazing experience. The difference that a certification shows is that you know that a certified growth hacker has knowledge of the beginning-to-end process of growth hacking, and that this person is supposed to look at more than just a single experiment to hack their growth.

There are a lot of cowboy growth hackers who simply repeat the same tactics, instead of trying to work from a repeatable process, where you identify problems through data, have a non-biased prioritization process for ideas and will focus on long-term learnings over direct impact. A proper certificate shows that you know what it takes.

When do you think clients should invest in the beginner growth hacking course you offer on your website rather than investing in working with you directly?

I created the course to make growth hacking available to a larger audience. I noticed that almost all other growth hacking courses fell into one of two buckets: (1) cheap (<$200), but focused on superficial growth tactics, or (2) good quality in-depth content, but very expensive ($1,500-$5,000). And I believe everybody should have access to that knowledge of how to build a systematic process to achieve long-term sustainable growth, so I created my own course, since I know that working one-on-one with me is also too expensive for most people.

Especially if you’d look at students or junior marketeers, for whom I created a proper beginner growth hacking course that will teach you 20% of the knowledge that is necessary to achieve the first 80% of the results.

Growth hacking does have some noticeable differences from marketing, as outlined on your website. How should clients make the decision between working with you, a growth hacker, instead of with a marketer?

The choice between working with a growth hacker versus a digital marketer is not a one-or-the-other choice; the fields are very different in focus and actually complementary to each other. Growth hacking is great to kickstart growth, test new opportunities and see what tactics work. Marketeers should be there to continue where the growth hackers left off: build out those strategies, maintain customer engagement and keep tactics fresh and relevant. You shouldn’t hire a growth hacker to maintain your marketing strategies; they’re excited to make new growth steps and would get bored when they can’t test new ideas.

Most of the time, I help a client get up to speed, show which opportunities are valuable and give them a strategy to execute. Then I hand it over to marketing for the long-term execution and coach them on the execution, and step back in when there’s a need for new growth input.

What are some common misconceptions about growth hacking?

A lot of growth hackers still present growth hacking as a perfect approach, where thanks to our data-driven way of working we can always make the right moves. But that’s not true: The hard data that you see in your analytics tools, can only tell you what is slowing down your growth, but not why your growth slows down there. While the “why” is what we build our experiments on top of … many growth hackers just fill that with their own assumptions to keep their speed, but that’s not sustainable long term.

Next to the hard data, you need soft data: the why. And that comes from talking with customers, running hypothesis-focused experiments (not result-focused) and maybe by looking at your feedback from customer support or surveys. Every time I implement a soft data feedback loop with my clients, I see that we increase our experiment effectiveness from 1 in 10 up to 1 in 3.

What trends are you seeing in the growth hacking world right now?

The growth industry is definitely maturing. Less hacks, more teams, more focus on velocity. Everybody within the field is getting to know the best practices very quickly and implementing them even quicker. So then what? We need more knowledge, more qualitative feedback and a more systematic approach to scale up our impact, to be able to rise above best practices and implement truly relevant and sophisticated tactics for our businesses. Since the field is maturing, you see people starting to get rid of the shoestring tools.

For this reason, I’m currently rolling out a growth management tool for growth teams, called Upgrow, where teams can more easily manage their experiment velocity, report to stakeholders with the click of a button and make sure that they systemize the knowledge retention from their articles to build companywide knowledge. And you see that mature growth teams need this kind of software to really level up and manage these trends that are putting stress on their process due to the growth of their company.

What do startups continue to get wrong?

Most startups just keep perfecting their product forever-and-ever: “Just this one extra feature and then we go live.” I can understand that, since north-star metrics, NPS scores and product-led growth are dominating the conversation around startup growth nowadays, but let me be real: You will never be fully done. There will always be a next feature. And you will only have a benefit if you grow alongside your customers. Put a “coming soon” on your website for the features that are in the making, and just start selling and scaling up your growth efforts: Different channels bring different kinds of users, who will have new demands, so you have to be adapting all the time. Not just now.

Powered by WPeMatico

In a company’s early days, the difference between C-level executives and the rest of the organization is simple — employees can walk away from a failure, but the leaders cannot. Under these conditions, certain kinds of people thrive in leadership roles and can take a company from ideation to production.

While there’s no magic formula for what works and what doesn’t, successful startups share common traits in terms of the way their foundational leadership teams are built.

We’ve all experienced what it looks like on the negative end of the spectrum — people making points simply to hear their own voice, leaders competing for credit and clashing agendas. When people would rather be heard than contribute, the output suffers. Members of a healthy leadership team are unafraid to let others have the limelight, because they trust the mission and the culture they’ve built together.

An honest self-assessment is necessary and this is something that only exceptional and selfless founders are capable of.

We are all imperfect human beings, founders included. There are always going to be moments that leaders can’t predict, and mistakes come with the territory. The right leadership team should be able to mitigate the unexpected, and sometimes make the future easier to predict. Putting the right people in the right roles early on can be the difference between success and failure — and that starts at the top.

Investors love founder-CEOs, and founders are often fantastic candidates for this role. But not everyone can do it well, and more importantly, not everyone wants to.

Startup founders should ask themselves a few questions before they lose sleep over the prospect of handing over the reigns:

An honest self-assessment is necessary and this is something that only exceptional and selfless founders are capable of. In many cases, founders decide they need outside help to fill the role. While a CEO may not be your first hire — or even one of the first five — the person you choose will ultimately occupy your organization’s most critical leadership role, so choose wisely.

What to look for: Ambitious vision grounded in execution reality. Your CEO should have hands-on experience that allows them to see around corners, predict pitfalls and identify opportunities.

What to watch out for: Leaders who lack respect for the founding vision or the ability to hire and balance an executive team quickly. A good CEO should be able to manage short-term cash flow and go-to-market needs without compromising the true north, while building a foundation and culture for the long term.

Powered by WPeMatico

Last week, Deliveroo made news when it announced it was preparing to leave the Spanish market. The recently listed Deliveroo couched its explanation in market terms, noting its market position in Spanish on-demand delivery wasn’t sufficient to warrant continued investment. Left unmentioned: A Spanish legal change requiring companies that previously depended on freelance couriers to hire their delivery staff.

Race Capital’s Edith Yeung helped explain the Deliveroo choice to The Exchange, saying the Spanish market doesn’t have a very large population, which may mean that the “potential upside for being #1 in Spain has [a] ceiling.”

While she noted that she doesn’t have access to Deliveroo data, her statement jibes with the company’s own comment that Spain made up less than 2% of its aggregate gross transaction value (GTV) in the first half of 2021.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on Extra Crunch or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

One company exiting a market is not a big deal, but we were curious about Deliveroo’s comments regarding the need for market leadership — or something close to it — to warrant continued investment. Is this the common reality for startups battling for market position, no matter if those markets are cities or countries?

Some startup markets have trended toward monopolies or duopolies. The Uber-Didi battle in China led to the companies agreeing to stop competing. Uber also recently sold its Uber Eats business in India to Zomato. In the United States, Uber and Lyft’s smaller competitors have long been forgotten and both the American ride-hailing giants continue to battle for dominance.

There are other familiar examples of this trend of consolidation. The food delivery game is concentrated amongst leading players. Postmates failed to survive as an independent company, winding up as part of Uber’s operations. Perhaps Gopuff will manage to claw out a spot in the market, but DoorDash and Uber Eats together accounted for 83% of the U.S. food delivery business in June this year, per Second Measure data.

There are other familiar examples of this trend of consolidation. The food delivery game is concentrated amongst leading players. Postmates failed to survive as an independent company, winding up as part of Uber’s operations. Perhaps Gopuff will manage to claw out a spot in the market, but DoorDash and Uber Eats together accounted for 83% of the U.S. food delivery business in June this year, per Second Measure data.

It’s no surprise that some startup markets lean toward monopolies or duopolies. Many countries protect intellectual property via patents that can constrain new innovation to one or two players for an extended period of time. Monopolies can also arise when a new technology or method of business is invented — Google’s internet parsing search tech led to a nigh-monopoly in many markets, for example.

In businesses where efficiencies of scale have a large effect, monopolies can form when leading players consolidate smaller competitors until just one or two companies remain. Standard Oil is the canonical example of this process.

What’s interesting about the on-demand delivery market is that it is both incredibly expensive but isn’t very technologically difficult to get into, which has meant that many companies have jumped into the sector around the world. This means on-demand delivery is the opposite of other patent-protected markets from which we might expect monopolies to form or competition to be extinguished past the top two players.

Yet, it’s also an industry where economies of scale can play a key role in profit generation, and increased competition can lead to price wars and advertising tussles. It’s a ripe market, then, for consolidation, even if it lacks an exploitable IP base.

Powered by WPeMatico

I was four years old when my dad first showed me a computer. I immediately asked him if we could take it apart to see how it worked. I was hooked.

When I learned that Windows and Mac were based in the United States, I was 10. Since then, I’ve wanted to come here to launch my own tech business.

What I didn’t realize back then was that the first half of that dream — coming to the U.S. — would provide me with essential training for realizing the second half — launching a business.

As it turns out, the behaviors, attitude and mindset required to traverse the U.S. immigration system are many of the same ones required to navigate the uncertain waters of entrepreneurship.

The behaviors, attitude and mindset required to traverse the U.S. immigration system are many of the same ones required to navigate the uncertain waters of entrepreneurship.

In 2019, I launched Preflight, which makes smart and fast no-code test automation software for web applications. One big reason the business currently exists is that, in my journey to getting asylee status in the United States, I became really good at three things: accepting uncertainty, building resilience and maintaining a positive mental attitude.

I needed them all to get Preflight off the ground.

I had my first shot at making my longtime dream a reality when I was applying to college as an undergraduate. I figured if I could go to school in the United States, I could find a way to stay and start a business.

After doing some research, though, I realized that U.S. colleges were too expensive.

But I figured getting out of Turkey, my home country, would be a start. I looked around for affordable schools and saw that France had good options. So I went to France.

Unfortunately, even after three attempts, I wasn’t able to get a student visa. So I headed back to Turkey and went to college there. After graduation, I knew I had a second shot at the U.S.: a master’s degree. I applied to computer science programs and got accepted — a huge win!

I first arrived in Georgia, where I got my TOEFL certification, then enrolled at Tennessee State University, where I got a teaching assistantship.

Keep in mind, to do all this, I had to have the right visas. I needed a student visa for my master’s degree, but if I wanted to work after graduation, I’d need a work visa.

The thing is, though, I didn’t want to work at a “job.” I wanted to start my own business, which requires a different type of visa altogether.

Oh, and there was another factor at play: I was enrolled at Tennessee State from 2014 to 2016, during the lead-up to the election of Donald Trump. So in addition to trying to figure out which visa I could reasonably get, I had to deal with the fact that the rules for visas could all change in the coming months.

These experiences are similar to what many founders deal with every day in the process of launching and running a business.

We don’t know if our products will work or if they’ll find a market. We don’t know how changing regulations might affect what we’re doing. We have no idea when something like a pandemic will pull the rug out from everything we’ve built.

But we keep going anyway. In my experience, the most successful founders are the ones who don’t wait for all the pieces to fall into place — they know that will never happen. They’re the ones who do the best they can with what they have. They trust that they’ll be able to adapt and adjust when things inevitably change.

Which brings me to my next lesson.

Hearing “no” isn’t fun, especially when that “no” is about something you’ve wanted for more than a decade.

I experienced a lot of “no”s in my immigration journey, as one visa attempt after another failed. If I’d let any one of those failures stop me, I wouldn’t be where I am today — working at my own startup in the U.S.

The lesson I learned was to hear “no” as “not yet.” It’s been invaluable to me in my journey to becoming a founder.

For example: In 2014, while I was in graduate school, I learned about Y Combinator and decided that I wanted to be a part of it. Throughout grad school, I applied and got rejected three times.

The clock was ticking on my student visa, so I decided to shift my tactics. I applied to jobs at companies that were Y Combinator graduates to see what I could learn.

In 2016, I got hired at ShipBob, a Chicago-based company that was in Y Combinator’s Summer 2014 batch. I joined the team as its first full-time developer and the first one based in the States. From there, things changed dramatically.

For starters, I learned a lot. In my time with ShipBob — just two and a half years — we grew from 10 people to more than 400. I built two apps and applied to Y Combinator twice more and got rejected both times.

But in my work growing and leading a team of developers, I saw a need for a product that didn’t yet exist: a smart, fast, no-code test automation tool.

My team was spending way too much time building tests for ShipBob’s latest updates to make sure existing functionalities worked when we deployed. But when the code changed too quickly, our tests were outdated. It was incredibly frustrating.

Then we hired two quality assurance engineers and it took them four months to get 10% automated test coverage.

These problems led me to an aha moment: I could build a company to address this. A tool that is fast in test creation and can adapt to the UI changes.

That company is Preflight, and it’s the one that finally got me admitted to Y Combinator in the Winter 2019 batch. I was ecstatic when I heard that we’d been accepted. But then I realized that I couldn’t actually work on Preflight full time with my current visa status — at least, if I wanted to one day make a salary, I couldn’t.

And that brings me to my next point.

My professional life wasn’t the only thing that changed dramatically while I was at ShipBob. My immigration status also evolved.

ShipBob applied for and got me an H-1B visa, which made me eligible to work in the U.S.

But when I got accepted to Y Combinator on my sixth application, I knew I needed an alternative: If I left ShipBob to run Preflight, I would lose my H-1B and my ability to work in the U.S.

This kind of conundrum is all too familiar to most startup founders: There’s no new opportunity without a new challenge to accompany it.

So I did what any founder would do: I focused on the positive (I’d gotten into YC!) and dedicated myself to figuring out a different way to stay in the country.

First, I tried to apply for the EB-1 visa, but the required documentation was too burdensome. I don’t think any founder could prepare for that application without several months of preparation.

Then I tried the O-1. No luck.

So I asked ShipBob if I could take an unpaid sabbatical, which would let me keep my H-1B status while I attended Y Combinator and worked on Preflight. They agreed. My brothers, who had both moved to Chicago and started working at ShipBob (you’re welcome, guys!) agreed to support me (thanks, guys!).

Finally, I had a solution that worked — but only for the time being. If Preflight was successful, I’d have to find a different way to stay in the country.

Transferring my H-1B to Preflight wouldn’t work, in part because it would require me to yield 70% to 80% ownership to my co-founder and agree that he could fire me at any time.

But there was another option I’d been reluctant to lean on: asylee status. In 2016, there was an attempted coup in Turkey (that’s the official story, anyway). I won’t get into the political details, but my family and I were supporters of the movement blamed for the attempt. As a result, we were at risk of imprisonment if we stayed in Turkey — and eligible for asylum status in the U.S.

I applied, but hoped that I’d land a work visa in the meantime, partly because asylum status can take years to get approved and partly because there was no telling whether the current administration would change the rules to make me ineligible before my status came through.

When I got accepted to Y Combinator, my asylum status was pending. When my initial sabbatical from ShipBob ran out, it was still pending. I asked for an extension and got it (thanks, ShipBob!). A few months later, I figured I could not get the visa sorted. I wanted to focus on my business and use asylum-pending status, which would give me work authorization for two years. I was therefore able to work on and take a salary from Preflight.

My asylum was granted early this year, four years after applying. Getting asylee status was a big win because it meant I could realize my dream of running a business in the U.S. So I was, in some ways, at the resolution of my immigration journey — but I was just at the beginning of my journey as a founder.

Right away, I had my first experience applying all the lessons I’d learned in the last six years: We wanted to raise our first funding round. That funding would let me start taking a salary.

All told, we approached more than 100 VCs before we got a yes. But we did get that yes, and we raised a seed round of $1.2 million in September 2019.

It was a big win for Preflight, but it didn’t have the transformational power for the company I’d hoped for. That’s because, after closing our round, we didn’t focus on sales and marketing to the extent that we should have.

After several months of frustrating results, I consulted with my advisers about how to proceed. They offered me insight that seemed obvious once I had it — but that I may not have gotten on my own — which was discussing everything that’s happening internally with the investors. And the outcome was me being the CEO.

In the month and a half after I adjusted course based on my vision, I grew Preflight’s revenue 600% in just about two months.

The whole startup ethos of disrupting what’s not working to improve people’s lives is based on the premise that the world is constantly changing. The global disruption caused by COVID-19 underscored that in a major way.

Founders who accept that change is inevitable and who embrace uncertainty, develop resilience for when things go wrong, and maintain a positive mental attitude about the ups and (especially) the downs of running a startup will be the ones who succeed for the long haul.

I’ve known since I was 10 that I wanted to run a company in the United States. Given the choice, I would have opted for a much smoother road to entrepreneurship. But what I’ve discovered is that the difficult immigration path I had to follow provided exactly the training I needed to succeed in the challenging role of a founder.

Powered by WPeMatico

The startup world can be a rollercoaster. While investment continues to pour in — with both founders and investors looking for the next unicorn — the reality is that 90% of startups fail, with over half of those going under in the first three years.

I’ve founded two companies that I grew and sold (Mezi and Dhingana). I encountered many of the issues that new founders face, learned on the job, and thankfully persevered. Using the knowledge that I acquired in my previous companies, I’ve founded a third — Zeni — to try and help founders make more informed, sustainable financial decisions.

For many founders, a transformative idea and initial outside investment doesn’t translate into understanding the underlying financial complexities of running a business.

Whether you’re just wrapping your seed round, or on to Series B, avoiding these common issues is the best way to ensure that you’re set on solid ground and free to focus on your vision.

Startups go under for a variety of reasons. Some fail to achieve product-market fit in a scalable way. Many others simply run out of money. While the above two reasons are often cited as the two primary reasons for startup failure, they’re also related. If you don’t solve a market problem and don’t generate customers, you’re eventually going to run out of money.

Unfortunately, many of the startups that fail shouldn’t. They’re led by bright entrepreneurs with a great idea. But for many founders, a transformative idea and initial outside investment doesn’t translate into understanding the underlying financial complexities of running a business.

When you break down the various complexities founders face in understanding business finances, there are three primary hurdles they face:

All of the above issues put increased workload and strain on founders, which can lead to burnout. Owners, on average, spend around 40% of their working hours on tasks like hiring, HR and payroll. While hiring is integral to a founders’ day-to-day role, other administrative tasks related to finance, HR and payroll distract founders from focusing on their overall vision and goals.

The good news is that by being aware of the above issues, you can solve them and eliminate the consequences of burnout, distraction and, ultimately, failure. Let’s talk about how.

The financial decision-making and tasks of most startups start and stop with the founder. This means that bookkeeping, bill paying, invoicing, financial projections, employee payments and taxes all run into a bottleneck. Even worse, each of these functions requires another employee, vendor or third-party expert — finance firms, admins, CFOs, CPA firms — each using its own software and applications to accomplish their goals.

Each of these parties is reporting back up to the founder, who is then in charge of making sense of it all and disseminating the information to the entities that need it. This means that not only is everything slower, but often things fall through the cracks, as communication can become a serious issue.

Worse still, this creates cash flow problems, as bills go unpaid, invoices go unsent, and important financial documents are delayed. I’ve seen revenue go unreported and invoices unsent and uncollectable due to the fragmentation-bottleneck system most founders experience.

Powered by WPeMatico

Refurbed, a European marketplace for refurbished electronics which raised a $17 million Series A round of funding last year, has now raised a $54 million Series B funding led by Evli Growth Partners and Almaz Capital.

They are joined by existing investors such as Speedinvest, Bonsai Partners and All Iron Ventures, as well as a group of new backers — Hermes GPE, C4 Ventures, SevenVentures, Alpha Associates, Monkfish Equity (Trivago Founders), Kreos, Expon Capital, Isomer Capital and Creas Impact Fund.

Refurbed is an online marketplace for refurbished electronics that are tested and renewed. These then tend to be 40% cheaper than new, and come with a 12-month warranty. The company claims that in 2020, it grew by 3x and reached more than €100 million in GMV.

Operating in Germany, Austria, Ireland, France, Italy and Poland, the startup plans to expand to three other countries by the end of 2021.

Riku Asikainen at Evli Growth Partners said: “We see the huge potential behind the way Refurbed contributes to a sustainable, circular economy.”

Peter Windischhofer, co-founder of refurbed, told me: “We are cheaper and have a wider product range, with an emphasis on quality. We focus on selling products that look new, so we end up with happy customers who then recommend us to others. It makes people proud to buy refurbished products.”

The startup has 130 refurbishers selling through its marketplace.

Other players in this space include Back Market (raised €48 million), Swappa (U.S.) and Amazon Renew. Refurbed also competes with Rebuy in Germany and Swapbee in Finland.

Powered by WPeMatico

As more people dust off their luggage and passports after stowing them away during the global pandemic, Elude aims to show travelers a new way to take spontaneous trips.

The Los Angeles-based startup launched its travel discovery mobile app Thursday, a budget-first search engine that shows people how far their money will take them. The platform’s personalized onboarding experience customizes trip packages and offers future travel suggestions based on those preferences.

The idea for the company came three years ago from Alex Simon, CEO, and Frankie Scerbo, CMO, who met in college and bonded over their love of traveling and would do so together any time they had a long weekend. One New Year’s they tried planning a trip, but everything was too expensive. Not being able to find something on their budget, they came up with the idea for Elude.

Rather than searching by destination, Elude gathers information like budget, time frame and trip preferences (think beach versus mountains), then presents users with flight and hotel results for destinations they may never have thought existed or could be traveled to on their budgets.

The company taps into the same flight and hotel databases that all online travel companies use that store hundreds of thousands of flights and hotels and only suggests hotels with 3.5 stars and above.

Elude app

The co-founders have now raised $2.1 million in seed funding led by a group of investors including Mucker Capital, Unicorn Ventures, Upfront Scout Fund, StartupO, Grayson Capital and Flight VC.

When Erik Rannala, co-founder and managing partner at Mucker Capital, initially invested in Elude, it was before the global pandemic. However, he sees travel getting back to normal, though with flights now more expensive than before, more people are looking for travel deals, something that wasn’t being addressed until Elude came along.

Travel is “a massive category,” with most people in either “look mode” or “book mode,” with the money only being made in book mode, Rannala said. By taking a budget-first approach, Elude is bridging people from look mode to book mode more quickly.

“The way they have done it is to help people discover something new based on their budget that is available to book right now,” he added. “It’s a unique way to solve the problem and to give people a good deal.”

With millenials spending over $200 billion annually on travel, Elude’s goal is to reduce the hours of scrolling in search of a trip and more time actively booking vacations. Whereas competitors may show flights only or hotels only, Elude produces flight and hotel packages.

“In just a few clicks, we can show you, for example, that you could go to Barcelona for the same price as Miami,” Scerbo told TechCrunch. “If you knew that kind of information, you would take a better trip. This opens doors to taking a trip every few months instead of the one or two trips a year most people take.”

Prior to today, Elude was in private beta mode where the company had amassed some 40,000 people on the waitlist. Simon said.

Elude plans to use the funding to advance technology, marketing function, operations and customer support.

Powered by WPeMatico

Statsig is taking the A/B testing applications that drive Facebook’s growth and putting similar functionalities into the hands of any product team so that they, too, can make faster, data-informed decisions on building products customers want.

The Seattle-based company on Thursday announced $10.4 million in Series A funding, led by Sequoia Capital, with participation from Madrona Venture Group and a group of individual investors, including Robinhood CPO Aparna Chennapragada, Segment co-founder Calvin French-Owen, Figma CEO Dylan Field, Instacart CEO Fidji Simo, DoorDash exec Gokul Rajaram, Code.org CEO Hadi Partovi and a16z general partner Sriram Krishnan.

Founder and CEO Vijaye Raji started the company with seven other former Facebook colleagues in February, but the idea for the company started more than a year ago.

He told TechCrunch that while working at Facebook, A/B testing applications, like Gatekeeper, Quick Experiments and Deltoid, were successfully built internally. The Statsig team saw an opportunity to rebuild these features from scratch outside of Facebook so that other companies that have products to build — but no time to build their own quick testing capabilities — can be just as successful.

Statsig’s platform enables product developers to run quick product experiments and analyze how users respond to new features and functionalities. Tools like Pulse, Experiments+ and AutoTune allow for hundreds of experiments every week, while business metrics guide product teams to build and ship the right products to their customers.

Raji intends to use the new funding to hire folks in the area of design, product, data science, sales and marketing. The team is already up to 14 since February.

“We already have a set of customers asking for features, and that is a good problem, but now we want to scale and build them out,” he added.

Statsig has no subscription or upfront fees and is already serving millions of end-users every month for customers like Clutter, Common Room and Take App. The company will always offer a free tier so customers can try out features, but also offers a Pro tier for 5 cents per thousand events so that when the customer grows, so does Statsig.

Raji sees adoption of Statsig coming from a few different places: developers and engineers that are downloading it and using it to serve a few million people a month, and then through referrals. In fact, the adoption the company is getting is “bottom up,” which is what Statsig wants, he said. Now the company is talking to bigger customers.

There are plenty of competitors for this product, including incumbents in the market, according to Raji, but they mostly focus on features, while Statsig provides insights and ties metrics back to features. In addition, the company has automated analysis where other products require manual set up and analysis.

Sequoia partner Mike Vernal worked at Facebook prior to joining the venture capital firm and had worked with Raji, calling him “a top 1% engineer” that he was happy to work with.

Having sat on many company boards, he has found that many companies spend a long time talking about sales and marketing, but very little on product because there is not an easy way to get precise numbers for planning purposes, just a discussion about what they did and plan to do.

What Vernal said he likes about Statsig is that the company is bringing that measurement aspect to the table so that companies don’t have to hack together a poorer version.

“What Statsig can do, uniquely, is not only set up an experiment and tell if someone likes green or blue buttons, but to answer questions like what the impact this is of the experiment on new user growth, retention and monitorization,” he added. “That they can also answer holistic questions and understand the impact on any single feature on every metric is really novel and not possible before the maturation of the data stack.”

Powered by WPeMatico

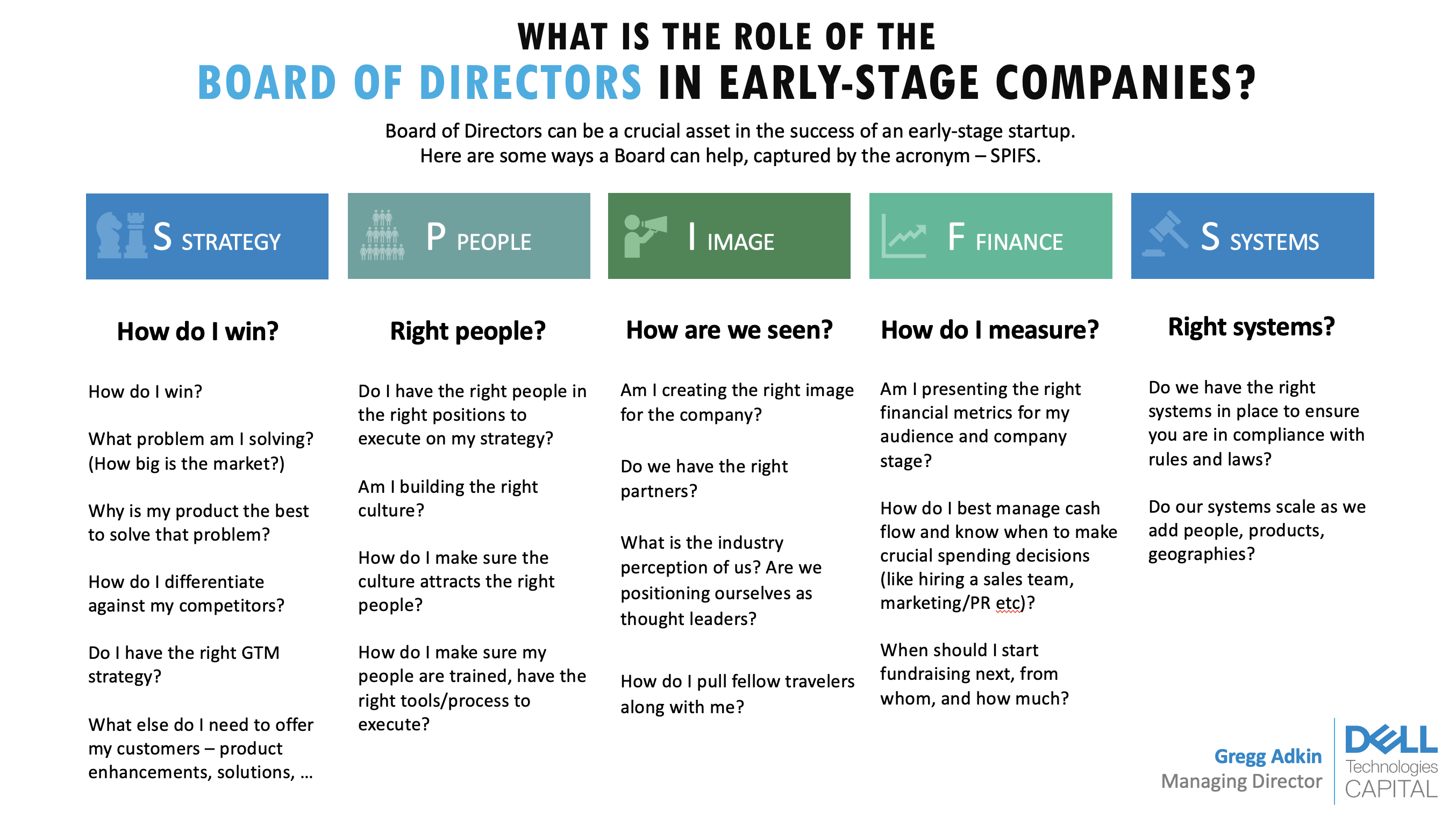

What’s the board’s role in an early-stage startup?

Startup founders frequently ask me about the role of a board of directors. A board can be a crucial asset in an early-stage startup.

Here’s a framework for how it can help drive success at your company: Strategy, People, Image, Finance and Systems for compliance, or “SPIFS.”

The board of directors helps with governance of the company. U.S. law requires that any company have one, though does not require how big it should be. By generic definition, the board of directors consists of elected individuals that represent shareholders. It is the governing body that provides company oversight and helps set business policy and strategy.

On a more practical level and in a startup environment, the board can aid in creating a successful business strategy, putting together the right management team, developing branding, building good financial habits, and avoiding legal and compliance issues. The needs and composition of the board will change depending on the startup’s stage, management and financing history (e.g., if there are preferred shareholders, investors that require a board seat and more).

Investors often ask founders about their board: It says a lot about their character, their judgment and their willingness to be challenged.

Investors often ask founders about their board for two reasons. First, it says a lot about their character, their judgment and their willingness to be challenged. The founder can typically choose who is on their board (through careful selection of investors and advisers) and negotiate a board structure they prefer.

Typically, a healthy board will have a good balance between common shareholders, preferred shareholders and independents. It also helps investors and analysts understand who will ask critical questions and give important advice to the company’s executive management, especially when the going gets tough (it inevitably does!).

After 20 years as a venture capitalist and board member, I boiled down the value of a board into five main pieces under the acronym SPIFS: Strategy, People, Image, Finance and Systems for compliance.

Image Credits: Dell Technologies Capital

Setting business strategy is one of the main ways that the board helps founders, especially if it’s their first time running a business. It is a valuable sounding board for validating that you have taken a sober account of the market and have the right plan to develop your product and acquire customers.

The board should ask these questions when guiding founders through setting strategy:

Powered by WPeMatico