Startups

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

FortressIQ, a startup that wants to bring a new kind of artificial intelligence to process automation called imitation learning, emerged from stealth this morning and announced it has raised $12 million.

The Series A investment came entirely from a single venture capital firm, Light Speed Venture Partners. Today’s funding comes on top of $4 million in seed capital the company raised previously from Boldstart Ventures, Comcast Ventures and Eniac Ventures.

Pankaj Chowdhry, founder and CEO of FortressIQ, says that his company basically replaces high-cost consultants who are paid to do time and motion studies and automates that process in a fairly creative way. It’s a bit like Robotics Process Automation (RPA), a space that is attracting a lot of investment right now, but instead of simply recording what’s happening on the desktop, and reproducing that digitally, it takes it a step further in a process called “imitation learning.”

“We want to be able to replicate human behavior through observation. We’re targeting this idea of how can we help people understand their processes. But imitation learning is I think the most interesting area of artificial intelligence because it focuses not on what AI can do, but how can AI learn and adapt,” he explained

They start by capturing a low-bandwidth movie of the process. “So we build virtual processors. And basically the idea is we have an agent that gets deployed by your enterprise IT group, and it integrates into the video card,” Chowdhry explained.

He points out that it’s not actually using a camera, but it captures everything going on, as a person interacts with a Windows desktop. In that regard it’s similar to RPA. “The next component is our AI models and computer vision. And we build these models that can literally watch the movie and transcribe the movie into what we call a series of software interactions,” he said.

Another key differentiator here is that they have built a data mining component on top of this, so if the person in the movie is doing something like booking an invoice, and stops to check email or Slack, FortressIQ can understand when an activity isn’t part of the process and filters that out automatically.

The product will be offered as a cloud service. Chowdhry’s previous company, Third Pillar Systems, was acquired by Genpact in 2013.

Powered by WPeMatico

Fivetran, a startup that builds automated data pipelines between data repositories and cloud data warehouses and analytics tools, announced a $15 million Series A investment led by Matrix Partners.

Fivetran helps move data from source repositories like Salesforce and NetSuite to data warehouses like Snowflake or analytics tools like Looker. Company CEO and co-founder George Fraser says the automation is the key differentiator here between his company and competitors like Informatica and SnapLogic.

“What makes Fivetran different is that it’s an automated data pipeline to basically connect all your sources. You can access your data warehouse, and all of the data just appears and gets kept updated automatically,” Fraser explained. While he acknowledges that there is a great deal of complexity behind the scenes to drive that automation, he stresses that his company is hiding that complexity from the customer.

The company launched out of Y Combinator in 2012, and other than $4 million in seed funding along the way, it has relied solely on revenue up until now. That’s a rather refreshing approach to running an enterprise startup, which typically requires piles of cash to build out sales and marketing organizations to compete with the big guys they are trying to unseat.

One of the key reasons they’ve been able to take this approach has been the company’s partner strategy. Having the ability to get data into another company’s solution with a minimum of fuss and expense has attracted data-hungry applications. In addition to the previously mentioned Snowflake and Looker, the company counts Google BigQuery, Microsoft Azure, Amazon Redshift, Tableau, Periscope Data, Salesforce, NetSuite and PostgreSQL as partners.

Ilya Sukhar, general partner at Matrix Partners, who will be joining the Fivetran board under the terms of deal sees a lot of potential here. “We’ve gone from companies talking about the move to the cloud to preparing to execute their plans, and the most sophisticated are making Fivetran, along with cloud data warehouses and modern analysis tools, the backbone of their analytical infrastructure,” Sukhar said in a statement.

They currently have 100 employees spread out across four offices in Oakland, Denver, Bangalore and Dublin. They boast 500 customers using their product including Square, WeWork, Vice Media and Lime Scooters, among others.

Powered by WPeMatico

It’s been a whirlwind few months for Forethought, a startup with a new way of looking at enterprise search that relies on artificial intelligence. In September, the company took home the TechCrunch Disrupt Battlefield trophy in San Francisco, and today it announced a $9 million Series A investment.

It’s pretty easy to connect the dots between the two events. CEO and co-founder Deon Nicholas said they’ve seen a strong uptick in interest since the win. “Thanks to TechCrunch Disrupt, we have had a lot of things going on including a bunch of new customer interest, but the biggest news is that we’ve raised our $9 million Series A round,” he told TechCrunch.

The investment was led by NEA with K9 Ventures, Village Global and several angel investors also participating. The angel crew includes Front CEO Mathilde Collin, Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev and Learnvest CEO Alexa von Tobel.

Forethought aims to change conventional enterprise search by shifting from the old keyword kind of approach to using artificial intelligence underpinnings to retrieve the correct information from a corpus of documents.

“We don’t work on keywords. You can ask questions without keywords and using synonyms to help understand what you actually mean, we can actually pull out the correct answer [from the content] and deliver it to you,” Nicholas told TechCrunch in September.

He points out that it’s still early days for the company. It had been in stealth for a year before launching at TechCrunch Disrupt in September. Since the event, the three co-founders have brought on six additional employees and they will be looking to hire more in the next year, especially around machine learning and product and UX design.

At launch, they could be embedded in Salesforce and Zendesk, but are looking to expand beyond that.

The company is concentrating on customer service for starters, but with the new money in hand, it intends to begin looking at other areas in the enterprise that could benefit from a smart information retrieval system. “We believe that this can expand beyond customer support to general information retrieval in the enterprise,” Nicholas said.

Powered by WPeMatico

Chewse, a food catering and company culture startup, just announced a $19 million fundraising round as it gears up to expand its operations in the Silicon Valley area. This brings Chewse’s total funding to more than $30 million. Chewse’s investors include Foundry Group, 500 Startups and Gingerbread Capital.

Instead of plopping down meals in the office and bouncing, Chewse aims to create a full experience for its customers by offering family-style meals. In order to ensure quality, Chewse employs drivers and meal hosts so that it can provide them with training. Chewse also offers it drivers and meal hosts benefits.

“We initially started with a contractor model but then very quickly started to realize our customers often mentioned the host or the driver in their feedback,” Chewse CEO and co-founder Tracy Lawrence told TechCrunch.

“I know there’s a lot of other companies that are like food tech or logistics but for us, it’s all about elevating and improving company culture,” Lawrence said. “We have technology but we’re investing in it to create an exceptional real-life experience.”

“On the tech side, we’re using a ton of machine learning and algorithms to learn what people like to eat and create custom meal schedules,” Lawrence said.

To date, Chewse has hundreds of customers across three markets. Chewse initially launched in Los Angeles, but paused operations for a little over one year in order to focus on achieving market profitability in San Francisco. Chewse has since relaunched in Los Angeles, in addition to launching in cities like Palo Alto and San Jose. As part of the Silicon Valley launch, Chewse has partnered with restaurants like Smoking Pig, HOM Korean Kitchen and Oren’s Hummus Shop.

Within the next year, the goal is to double the number of markets where Chewse operates. But Chewse faces tough competition in the corporate meal catering space.

Earlier this year, Square acquired Zesty to become part of its food delivery service, Caviar. The aim of the acquisition was to strengthen Caviar’s corporate food ordering business, Caviar for Teams.

At the time, Zesty counted about 150 restaurant customers in San Francisco, which is the only city in which it operates. Some of Zesty’s customers include Snap, Splunk and TechCrunch. Zesty, which first launched in 2013 under a different name, had previously raised $20.7 million in venture funding.

“Zesty is a direct competitor of ours for sure,” Lawrence said. “When we’re thinking about the things that set us apart from Zesty and ZeroCater, the investment in using the technology and building a meal algorithm — which is something we know they’re doing by hand — and then automatically calibrate when we’re getting feedback because we employ our hosts and our drivers. Yes, it’s more expensive for us but because it provides such a superior experience, we retain our customer longer.”

Powered by WPeMatico

I’ll be heading back to Europe in December to run a pitch-off in Wroclaw, Poland. It’s a bit out of the way, but well worth a visit if only for the sausages.

The event, called In-Ference, is happening on December 17 and you can submit to pitch here. The team will notify you if you have been chosen to pitch. The winner will receive a table at TC Disrupt in San Francisco.

I’m also thinking about an event in Warsaw on the 21st but WeWork didn’t look doable (and I don’t like co-working spaces). If anyone has thoughts on a new venue drop me a line at john@techcrunch.com. Otherwise, I’ll see you in Wroclaw! Wesołych Świat!

Powered by WPeMatico

Floom, the online marketplace and SaaS for independent florists, has raised $2.5 million in a seed funding. The round was round led by Firstminute Capital, and will be used by the London headquartered startup to continue to expand to the U.S., where it already operates in New York and L.A., and to further develop its software offering.

Additional investors include Tom Singh (founder of New Look), Pembroke VCT, Wing Chan (CTO digital experiences of The Hut Group), and Carlos Morgado (former CTO of Just Eat). Morgado has also joined Floom’s board.

Founded by 31-year-old Lana Elie in 2016, Floom bills itself as a curated marketplace for independent florists. Alongside this, the company’s technology platform gives florists the software and tools they need to create and deliver “beautifully crafted bouquets” to customers. It’s this SaaS play that Elie says sets Floom apart from competitors.

“We rely on a network [of florists], like many of the bigger competitors, so that we can offer same-day delivery without the risk of holding stock ourselves,,” she tells me. “But instead of telling the florists what to create and what to hold in stock, we built them an Etsy-like UI to design and deliver beautifully crafted bouquets to our online communities themselves”.

This sees florists provided with a “backend management dashboard” to create, allocate and manage inventory, and to co-ordinate with Floom’s marketplace. The software manages and tracks delivery, too.

“Customers receive more bouquet options, in more areas, by vetted florists, with the ultimate convenience of a seamless check-out and what everyone really wants: confirmation of safe receipt in their loved one’s hand,” explains Elie. “If the final product doesn’t match the picture, they get their money back, something that most competitors can’t offer, but we solved this by relying on the florists to generate the bouquet catalogue themselves”.

On the flower delivery front, Floom’s main competitors are Interflora in the U.K. (owned by 100-year-old conglomerate FTD in the U.S.), as well as 1-800-flowers and Teleflora. “There have been some new players in the flower space, but none solve the problem by creating better technologies,” argues the Floom founder.

“Floom’s not just a flower delivery service but a tech company. I wanted to solve a problem: showing customers all the amazing artisanal florists in their home cities, and making the experience of sending flowers enjoyable and hassle-free. On top of that, we wanted to create a fresh brand that appealed to an audience of my generation… and different from how you might typically think of the flower industry”.

With that said, Elie concedes that there is other florist software in existence, but says it doesn’t really consider the florists as a customer in the same way that Floom does. This is especially true in how the startup understands that the “brand and UI is just as important as functionality”.

“Florists are creative, skilled in a way that I’m definitely not, but when it comes to something like a website build, they’re paying the wrong people much more than they need to build badly UX’d sites,” she adds. “Florists are given no chance to really compete in a world where everything is digital. Building a management tool that speaks to all florists’ consumer facing channels (phone, email, chat, webshop, POS etc) will ultimately mean cost and time savings for the florist, less unnecessary waste for environmental purposes, and better products and delivery experiences for the customer”.

Powered by WPeMatico

Scooter startup Lime has sought to back peddle on an explanation given by its VP of global expansion late last week when asked why it had hired the controversial PR firm, Definers Public Affairs.

The opposition research firm, which has ties to the Republican Party, has been at the center of a reputation storm for Facebook, after a New York Times report last month suggested the controversial PR firm sought to leverage anti-semitic smear tactics — by sending journalists a document linking anti-Facebook groups to billionaire George Soros (after he had been critical of Facebook).

Last month it also emerged that other tech firms had engaged Definers — Lime being one of them. And speaking during an on stage interview at TechCrunch Disrupt Berlin last Thursday, Lime’s Caen Contee claimed it had not known Definers would use smear tactics.

Yet, as we reported previously, a Definers employee sent us an email pitch in October in which it wrote suggestively that “Bird’s numbers seem off”.

This pitch did not disclose the PR firm was being paid by Lime.

Asked about this last week Contee claimed not to know anything about Definers’ use of smear tactics, saying Lime had engaged the firm to work on its green and carbon free programs — and to try to understand “what were the levers of opportunity for us to really create the messaging and also to do our own research; understanding the life-cycle; all the pieces that are in a very complex business”.

“As soon as we understood they were doing some of these things we parted ways and finished our program with them,” he also said.

However, following the publication of our article reporting on his comments, a Lime spokesperson emailed with what the subject line billed as a “statement for your latest story”, tee-ing this up by writing: “Hoping you can update the piece”.

The statement went on to claim that Contee “misspoke” and “was inaccurate in his description of [Definers] work”.

However it did not specify exactly what Contee had said that was incorrect.

A short while later the same Lime spokesperson sent us another version of the statement with updated wording, now entirely removing the reference to Contee.

You can read both statements below.

As you read them, note how the second version of the statement seeks to obfuscate the exact source of the claimed inaccuracy, using wording that seeks to shift blame in way that a casual reader might interpret as external and outside the company’s control…

Statement 1:

Our VP of Global Expansion misspoke at TechCrunch Disrupt regarding our relationship with Definers and was inaccurate in his description of their work. As previously reported, we engaged them for a three month contract to assist with compiling media coverage reports, limited public relations and fact checking, and we are no longer working with Definers.

What was presented at Disrupt regarding our relationship with Definers and the description of their work was inaccurate. As previously reported, we engaged them for a three month contract to assist with compiling media coverage reports, limited public relations and fact checking, and we are no longer working with Definers.

Despite the Lime spokesperson’s hope for a swift update to our report, they did not respond when we asked for clarification on what exactly Contee had said that was “inaccurate”.

A claim of inaccuracy that does not provide any detail of the substance upon which the claim rests smells a lot like spin to us.

Three days later we’re still waiting to hear the substance of Lime’s claim because it has still not provided us with an explanation of exactly what Contee said that was ‘wrong’.

Perhaps Lime was hoping for a silent edit to the original report to provide some camouflaging fuzz atop a controversy of the company’s own making. i.e. that a PR firm it hired tried to smear a rival.

If so, oopsy.

Of course we’ll update this report if Lime does get in touch to provide an explanation of what it was that Contee “misspoke”. Frankly we’re all ears at this point.

Powered by WPeMatico

In order to have innovative smart city applications, cities first need to build out the connected infrastructure, which can be a costly, lengthy, and politicized process. Third-parties are helping build infrastructure at no cost to cities by paying for projects entirely through advertising placements on the new equipment. I try to dig into the economics of ad-funded smart city projects to better understand what types of infrastructure can be built under an ad-funded model, the benefits the strategy provides to cities, and the non-obvious costs cities have to consider.

Consider this an ongoing discussion about Urban Tech, its intersection with regulation, issues of public service, and other complexities that people have full PHDs on. I’m just a bitter, born-and-bred New Yorker trying to figure out why I’ve been stuck in between subway stops for the last 15 minutes, so please reach out with your take on any of these thoughts: @Arman.Tabatabai@techcrunch.com.

When we talk about “Smart Cities”, we tend to focus on these long-term utopian visions of perfectly clean, efficient, IoT-connected cities that adjust to our environment, our movements, and our every desire. Anyone who spent hours waiting for transit the last time the weather turned south can tell you that we’ve got a long way to go.

But before cities can have the snazzy applications that do things like adjust infrastructure based on real-time conditions, cities first need to build out the platform and technology-base that applications can be built on, as McKinsey’s Global Institute explained in an in-depth report released earlier this summer. This means building out the network of sensors, connected devices and infrastructure needed to track city data.

However, reaching the technological base needed for data gathering and smart communication means building out hard physical infrastructure, which can cost cities a ton and can take forever when dealing with politics and government processes.

Many cities are also dealing with well-documented infrastructure crises. And with limited budgets, local governments need to spend public funds on important things like roads, schools, healthcare and nonsensical sports stadiums which are pretty much never profitable for cities (I’m a huge fan of baseball but I’m not a fan of how we fund stadiums here in the states).

As city infrastructure has become increasingly tech-enabled and digitized, an interesting financing solution has opened up in which smart city infrastructure projects are built by third-parties at no cost to the city and are instead paid for entirely through digital advertising placed on the new infrastructure.

I know – the idea of a city built on ad-revenue brings back soul-sucking Orwellian images of corporate overlords and logo-paved streets straight out of Blade Runner or Wall-E. Luckily for us, based on our discussions with developers of ad-funded smart city projects, it seems clear that the economics of an ad-funded model only really work for certain types of hard infrastructure with specific attributes – meaning we may be spared from fire hydrants brought to us by Mountain Dew.

While many factors influence the viability of a project, smart infrastructure projects seem to need two attributes in particular for an ad-funded model to make sense. First, the infrastructure has to be something that citizens will engage – and engage a lot – with. You can’t throw a screen onto any object and expect that people will interact with it for more than 3 seconds or that brands will be willing to pay to throw their taglines on it. The infrastructure has to support effective advertising.

Second, the investment has to be cost-effective, meaning the infrastructure can only cost so much. A third-party that’s willing to build the infrastructure has to believe they have a realistic chance of generating enough ad-revenue to cover the costs of the projects, and likely an amount above that which could lead to a reasonable return. For example, it seems unlikely you’d find someone willing to build a new bridge, front all the costs, and try to fund it through ad-revenue.

A LinkNYC kiosk enabling access to the internet in New York on Saturday, February 20, 2016. Over 7500 kiosks are to be installed replacing stand alone pay phone kiosks providing free wi-fi, internet access via a touch screen, phone charging and free phone calls. The system is to be supported by advertising running on the sides of the kiosks. ( Richard B. Levine) (Photo by Richard Levine/Corbis via Getty Images)

To get a better understanding of the types of smart city hardware that might actually make sense for an ad-funded model, we can look at the engagement levels and cost structures of smart kiosks, and in particular, the LinkNYC project. Smart kiosks – which provide free WiFi, connectivity and real-time services to citizens – have been leading examples of ad-funded smart city projects. Innovative companies like Intersection (developers of the LinkNYC project), SmartLink, IKE, Soofa, and others have been helping cities build out kiosk networks at little-to-no cost to local governments.

LinkNYC provides public access to much of its data on the New York City Open-Data website. Using some back-of-the-envelope math and a hefty number of assumptions, we can try to get to a very rough range of where cost and engagement metrics generally have to fall for an ad-funded model to make sense.

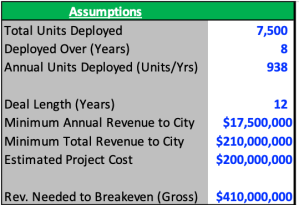

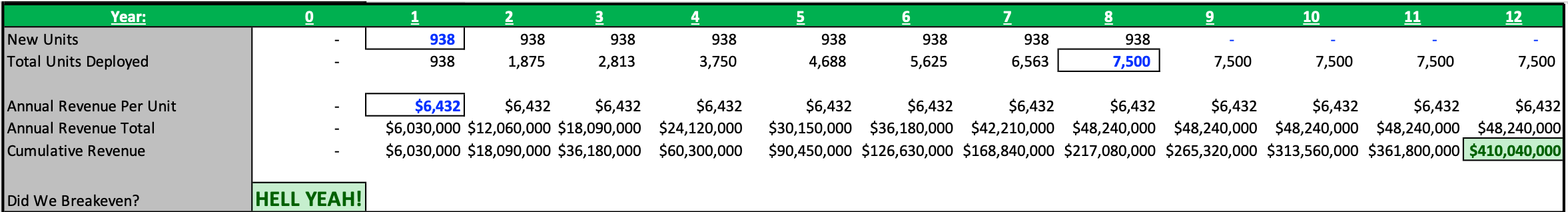

To try and retrace considerations for the developers’ investment decision, let’s first look at the terms of the deal signed with New York back in 2014. The agreement called for a 12-year franchise period, during which at least 7,500 Link kiosks would be deployed across the city in the first eight years at an expected project cost of more than $200 million. As part of its solicitation, the city also required the developers to pay the greater of either a minimum annual payment of at least $17.5 million or 50 percent of gross revenues.

Let’s start with the cost side – based on an estimated project cost of around $200 million for at least 7,500 Links, we can get to an estimated cost per unit of $25,000 – $30,000. It’s important to note that this only accounts for the install costs, as we don’t have data around the other cost buckets that the developers would also be on the hook for, such as maintenance, utility and financing costs.

Source: LinkNYC, NYC.gov, NYCOpenData

Turning to engagement and ad-revenue – let’s assume that the developers signed the deal with the expectations that they could at least breakeven – covering the install costs of the project and minimum payments to the city. And for simplicity, let’s assume that the 7,500 links were going to be deployed at a steady pace of 937-938 units per year (though in actuality the install cadence has been different). In order for the project to breakeven over the 12-year deal period, developers would have to believe each kiosk could generate around $6,400 in annual ad-revenue (undiscounted).

Source: LinkNYC, NYC.gov, NYCOpenData

The reason the kiosks can generate this revenue (and in reality a lot more) is because they have significant engagement from users. There are currently around 1,750 Links currently deployed across New York. As of November 18th, LinkNYC had over 720,000 weekly subscribers or around 410 weekly subscribers per Link. The kiosks also saw an average of 18 million sessions per week, or 20-25 weekly sessions per subscriber, or around 10,200 weekly sessions per kiosk (seasonality might even make this estimate too low).

And when citizens do use the kiosks, they use it for a long time! The average session for each Link unit was four minutes and six seconds. The level of engagement makes sense since city-dwellers use these kiosks in time or attention-intensive ways, such making phone calls, getting directions, finding information about the city, or charging their phones.

The analysis here isn’t perfect, but now we at least have a (very) rough idea of how much smart kiosks cost, how much engagement they see, and the amount of ad-revenue developers would have to believe they could realize at each unit in order to ultimately move forward with deployment. We can use these metrics to help identify what types of infrastructure have similar profiles and where an ad-funded project may make sense.

Bus stations, for example, may cost about $10,000 – $15,000, which is in a similar cost range as smart kiosks. According to the MTA, the NYC bus system sees over 11.2 million riders per week or nearly 700 riders per station per week. Rider wait times can often be five-to-ten minutes in length if not longer. Not to mention bus stations already have experience utilizing advertising to a certain degree. Projects like bike-share docking stations and EV charging stations also seem to fit similar cost profiles while having high engagement.

And interactions with these types of infrastructure are ones where users may be more receptive to ads, such as an EV charging station where someone is both physically engaging with the equipment and idly looking to kill up sometimes up to 30 minutes of time as they charge up. As a result, more companies are using advertising models to fund projects that fit this mold, like Volta, who uses advertising to offer charging stations free to citizens.

When it makes sense for cities and third-party developers, advertising-funded smart city infrastructure projects can unlock a tremendous amount of value for a city. The benefits are clear – cities pay nothing, citizens are offered free connectivity and real-time information on local conditions, and smart infrastructure is built and can possibly be used for other smart city applications down the road, such as using locational data tracking to improve city zoning and congestion.

Yes, ads are usually annoying – but maybe understanding that advertising models only work for specific types of smart city projects may help quell fears that future cities will be covered inch-to-inch in mascots. And ads on projects like LinkNYC promote local businesses and can tap into idiosyncratic conditions and preferences of regional communities – LinkNYC previously used real-time local transit data to display beer ads to subway riders that were facing heavy delays and were probably in need of a drink.

Like everyone’s family photos from Thanksgiving, the picture here is not all roses, however, and there are a lot of deep-rooted issues that exist under the surface. Third-party developed, advertising-funded infrastructure comes with externalities and less obvious costs that have been fairly criticized and debated at length.

When infrastructure funding is derived from advertising, concerns arise over whether services will be provided equitably across communities. Many fear that low-income or less-trafficked communities that generate less advertising demand could end up having poor infrastructure and maintenance.

Even bigger points of contention as of late have been issues around data consent and treatment. I won’t go into much detail on the issue since it’s incredibly complex and warrants its own lengthy dissertation (and many have already been written).

But some of the major uncertainties and questions cities are trying to answer include: If third-parties pay for, manage and operate smart city projects, who should own data on citizens’ living behavior? How will citizens give consent to provide data when tracking systems are built into the environment around them? How can the data be used? How granular can the data get? How can we assure citizens’ information is secure, especially given the spotty track records some of the major backers of smart city projects have when it comes to keeping our data safe?

The issue of data treatment is one that no one has really figured out yet and many developers are doing their best to work with cities and users to find a reasonable solution. For example, LinkNYC is currently limited by the city in the types of data they can collect. Outside of email addresses, LinkNYC doesn’t ask for or collect personal information and doesn’t sell or share personal data without a court order. The project owners also make much of its collected data publicly accessible online and through annually published transparency reports. As Intersection has deployed similar smart kiosks across new cities, the company has been willing to work through slower launches and pilot programs to create more comfortable policies for local governments.

But consequential decisions related to third-party owned smart infrastructure are only going to become more frequent as cities become increasingly digitized and connected. By having third-parties pay for projects through advertising revenue or otherwise, city budgets can be focused on other vital public services while still building the efficient, adaptive and innovative infrastructure that can help solve some of the largest problems facing civil society. But if that means giving up full control of city infrastructure and information, cities and citizens have to consider whether the benefits are worth the tradeoffs that could come with them. There is a clear price to pay here, even when someone else is footing the bill.

Powered by WPeMatico

At the very beginning, there were 13 startups. After two days of incredibly fierce competition, we now have a winner.

Startups participating in the Startup Battlefield have all been hand-picked to participate in our highly competitive startup competition. They all presented in front of multiple groups of VCs and tech leaders serving as judges for a chance to win $50,000 and the coveted Disrupt Cup.

After hours of deliberations, TechCrunch editors pored over the judges’ notes and narrowed the list down to five finalists: Imago AI, Kalepso, Legacy, Polyteia and Spike.

These startups made their way to the finale to demo in front of our final panel of judges, which included: Sophia Bendz (Atomico), Niko Bonatsos (General Catalyst), Luciana Luxandru (Accel), Ida Tin (Clue), Matt Turck (FirstMark Capital) and Matthew Panzarino (TechCrunch).

And now, meet the Startup Battlefield winner of TechCrunch Disrupt Berlin 2018.

Legacy is tackling an interesting problem: the reduction of sperm motility as we age. By freezing men’s sperm, this Swiss-based company promises to keep our boys safe and potent as we get older, a consideration that many find vital as we marry and have kids later.

Read more about Legacy in our separate post.

Imago AI is applying AI to help feed the world’s growing population by increasing crop yields and reducing food waste. To accomplish this, it’s using computer vision and machine learning technology to fully automate the laborious task of measuring crop output and quality.

Read more about Imago AI in our separate post.

Powered by WPeMatico

N26 announced today that it now has more than 2 million customers — up from 1.5 million in October.

The German fintech startup’s CEO Valentin Stalf was interviewed onstage at Disrupt Berlin with Tandem CEO Ricky Knox, where they discussed the growth of what are sometimes called challenger banks or neobanks — new banks that are taking on the incumbents by focusing on digital tools.

Stalf said N26 is seeing more than €1.5 billion in transactions each month, with €1 billion in deposits. He also discussed the company’s recent launch in the United Kingdom — he didn’t know the exact number of U.K. users, but estimated that the company has tens of thousands of U.K. accounts, with between 1,500 and 2,000 new signups on a single day three days ago.

Meanwhile, Knox said Tandem now has nearly half a million users in the U.K. (“This year, we’re seeing everybody’s growing really quickly.”) He also noted that because Tandem allows users to aggregate different accounts, he’s noticed some of those users are starting to become more focused on individual services.

“What tends to happen, particularly with the early adopter audience, is they will open [an] account with everybody because they want to check it out, they want to get the best product,” he said. “And then what you’ll see is over time, them kind of picking a horse — depending on the functionality they like, depending on, you know, the service they’re getting there — and settling in.”

Tandem is also expanding geographically, specifically to Hong Kong through a deal with Convoy Global Holdings. Asked why he’s making the leap to Asia before launching in other European markets, Knox said, “There are a load of massive Asian markets … The exciting thing here is the opportunity, as I said, for a global bank, and some of these Asian markets are really ripe for disruption.”

In discussing the different models for challenger banks, Knox warned against the dangers of the “marketplace bank” model, where banks make money by connecting customers to third-party services.

“What we found is, the more we try and push revenue in that area there, the less customers love it,” he said. “That’s the challenge with marketplaces: If you build your business model around it, you’ve got an inherent contradiction between customers loving you less when you make more money.”

Instead, Knox argued that customers have a better experience if the bank is willing to recommend free or low-priced services: “And actually at the backend, we’re still making money the same way the bank makes money. So we’re able to fund, if you like, all this great customer stuff at the front end.”

Moderator Romain Dillet quickly pointed out that Stalf was shaking his head while Knox was making his arguments.

“What we see with our customers is, I think if we have a great product, they’re normally also willing to pay a little bit for it,” Stalf said. “It needs to be transparent, and it needs to be a good value to consumers. But I think it’s untrue that customers are always not choosing a product if you price it.”

As for whether we’ll be seeing consolidation in the industry over the next few years, Knox argued, “I’d say there’s plenty of room for the existing cadre of neobanks to be incredibly successful on a global basis without any mergers or acquisitions.” He suggested it’s more likely that the established banks start trying to acquire the challengers, although he said, “That’s not a route we want to take.”

“I think there’s a couple players that are set for being a global bank, and I think we are trying to take the shot to be a global bank,” Stalf added. “I think it’s about building up 50 to 100 million users in the next couple years.”

Powered by WPeMatico