Startups

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Editor’s note: This post is a part of our latest initiative to demystify design and find the best brand designers and agencies in the world who work with early-stage companies — nominate a talented brand designer you’ve worked with.

During a decade as the manager of the in-house design team at open-source technology company Red Hat, Chris Grams learned that brand design is best when informed by a company’s culture and community.

He felt a natural push toward an open, collaborative attitude, distinct from how many companies approached design at that time. It was the early 2000s, and most companies saw their interactions with customers as a one-way street. In open source, it was an intersection.

“You almost break down the company and the community of people who surround the brand,” says Grams, currently head of marketing at Tidelift, an open-source software management firm, and author of The Ad-Free Brand. “Now it feels like pretty standard operating procedure for the best brands that have the best relationship with their communities.”

This shift has a large influence on the question of when you should hire an in-house designer versus a contractor to do your branding design.

After leaving Red Hat in 2009, Grams helped start New Kind, a branding agency that provides contract design services mostly to tech companies. This new vantage point allowed him to see drawbacks and advantages for companies in outsourcing design versus bringing it in-house.

One of the key benefits of in-housing is the designer’s intimacy with the deeply held values and culture of the company, which makes their branding work feel more authentic.

“The internal agency’s power really reveals itself when people are deeply part of the mission of the company,” says Grams. “It comes through in the work. You get an amazing work product.”

The second benefit, especially for tech companies, is the depth of understanding in-house designers can develop about the company’s products and services. And the third is that a dedicated in-house designer can be directed as needed to respond to pressing priorities.

“You can have them stop on a dime,” says Grams. “Say a competitor comes out with a big launch and you need to have something out within 24 hours. You can work on it right away.”

These are real benefits, but they may not outweigh the advantages of contracting out your design to a high-quality agency.

A major benefit of an agency is that you can hire people with a level of expertise and variety of skills that would be out of reach for an in-house team. When Grams was at New Kind, for example, “we had a combined 30 years of experience with open-source branding work,” he says.

An agency can also provide the bandwidth to take on non-priority tasks such as a rebrand or a special series that in-house teams are often too work-strapped to take on.

Hiring an agency also has advantages in terms of flexibility and cost. The ability to customize the timing and amount of design work to your needs can be less expensive over time, even if each working hour is more expensive.

“You can ramp down and ramp up with an agency,” says Grams. “It’s impossible to do that with people… You’re paying that extra margin to have that flexibility.”

There’s a lot to think about, but Grams advises prioritizing the need for your design to be authentic to your culture… or not.

“I think the biggest thing is the power of your culture, frankly,” says Grams. “If you have a company where culture is not an asset, I would not build an in-house design team… But if you’re building a mission-driven organization or an organization where culture is super important, that’s where I would take an extra-long look at building an internal agency.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Zoom, the only profitable unicorn in line to go public, priced its initial public offering at between $28 and $32 per share Monday morning. The video conferencing business plans to trade on the Nasdaq under the ticker symbol “ZM.”

Zoom, valued at $1 billion in 2017, initially filed to go public in March. According to its amended IPO filing, the company will raise up to $348.1 million by selling 10.9 million Class A shares. The offering will grant Zoom a fully diluted market value of $8.7 billion, a more than 8x increase to its latest private market valuation.

Although the company has garnered praise for its stellar financials — Zoom posted $330 million in revenue in the year ending January 31, 2019, a remarkable 2x increase year-over-year, with a gross profit of $269.5 million — the road to IPO hasn’t been without hiccups.

The company’s founder and chief executive officer Eric Yuan last night published an open letter concerning the conduct of Zoom’s chief financial officer Kelly Steckelberg. According to the letter, Zoom was recently informed by an anonymous source that Steckelberg had an “undisclosed, consensual relationship” during her tenure at a previous employer.

Steckelberg was most recently the CEO of the online dating site Zoosk; before that, she was a senior director in consumer finance at Cisco . The letter does not specify where the relationship took place, when or with whom.

Losing a CFO mere days before an IPO would have been a major loss for Zoom. CFOs often become the face of the IPO, handling the grueling tasks associated with crafting an IPO prospectus, leading the roadshow and more, while also maintaining day-to-day financial operations.

Yuan writes that the Zoom’s board of directors conducted a full investigation into the matter and determined that Steckelberg would stay on as Zoom’s CFO: “Kelly expressed regret for what transpired at her former employer, took ownership for the situation, and made clear to us that she had learned valuable lessons from the experience,” he wrote.

“We appreciated Kelly’s openness and candor during this process,” he continued. “It is clear that this matter related only to circumstances at her former employer. During Kelly’s tenure at Zoom, she has been an incredible contributor, as well as a model steward of our culture, values, and high standards since joining the Company.”

We reached out to Zoosk for comment. Zoom declined to comment further.

Zoom, expected to make the final call on its IPO price next Wednesday, will likely price at the top of the range and see a clean pop on its first day on the markets given its clean track record and positive financials. The business was founded in 2011 by Eric Yuan, an early engineer at WebEx, which sold to Cisco for $3.2 billion in 2007. Before launching Zoom, he spent four years at Cisco as its vice president of engineering.

Zoom has raised $145 million to date from investors, including Emergence Capital, which owns a 12.2 percent pre-IPO stake; Sequoia Capital (11.1 percent pre-IPO stake); Digital Mobile Venture (8.5 percent), a fund affiliated with former Zoom board member Samuel Chen; and Bucantini Enterprises Limited (5.9 percent), a fund owned by Li Ka-shing, a Chinese billionaire and among the richest people in the world.

Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs are leading its offering.

Powered by WPeMatico

The San Francisco-based startup Branch International, which makes small personal loans in emerging markets, has raised $170 million and announced a partnership with Visa to offer virtual, pre-paid debit cards to Branch client networks in Africa, South-Asia and Latin America.

Branch — which has 150 employees in San Francisco, Lagos, Nairobi, Mexico City and Mumbai — makes loans starting at $2 to individuals in emerging and frontier markets. The company also uses an algorithmic model to determine credit worthiness, build credit profiles and offer liquidity via mobile phones.

“We’ll use [the money] to deepen existing business in Africa. Later this year we’ll announce high-yield savings accounts…in Africa,” says Branch co-founder and chief executive Matt Flannery.

The $170 million round from Foundation Capital and its new debit card partner, Visa, will support Branch’s international expansion, which could include Brazil and Indonesia, according to Flannery. Branch launched in Mexico and India within the last year. In Africa, it offers its services in Kenya, Nigeria and Tanzania.

A potential Branch customer

The Branch-Visa partnership will allow individuals to obtain virtual Visa accounts with which to create accounts on Branch’s app. This gives Branch larger reach in countries such as Nigeria — Africa’s most populous country with 190 million people — where cards have factored more prominently than mobile money in connecting unbanked and underbanked populations to finance.

Founded in 2015, Branch started operating in Kenya, where mobile money payment products such as Safaricom’s M-Pesa (which does not require a card or bank account to use) have scaled significantly. M-Pesa now has 25 million users, according to sector stats released by the Communications Authority of Kenya. Branch has more than 3 million customers and has processed 13 million loans and disbursed more than $350 million, according to company stats.

Branch has one of the most downloaded fintech apps in Africa, per Google Play app numbers combined for Nigeria and Kenya, according to Flannery.

Already profitable, Branch International expects to reach $100 million in revenues this year, with roughly 70 percent of that generated in Africa, according to Flannery.

In addition to Visa and Foundation Capital, the $170 Series C round included participation from Branch’s existing investors Andreessen Horowitz, Trinity Ventures, Formation 8, the IFC, CreditEase and Victory Park, while adding new investors Greenspring, Foxhaven and B Capital.

Branch last raised $70 million in 2018. The company’s overall VC haul and $100 million revenue peg register as pretty big numbers for a startup focused primarily on Africa. Pan-African e-commerce startup Jumia, which also announced its NYSE IPO last month, generated $140 million in revenue (without profitability) in 2018.

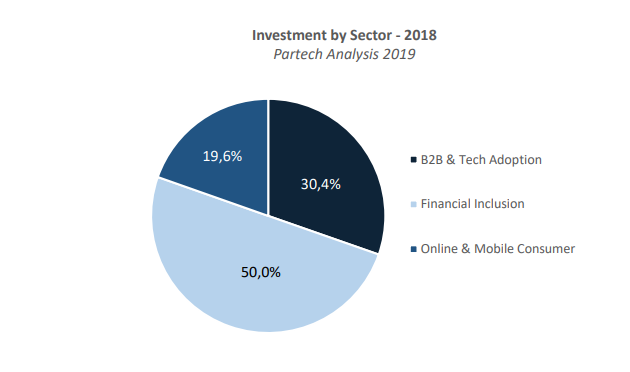

Startups building financial technologies for Africa’s 1.2 billion population have gained the attention of investors. As a sector, fintech (or financial inclusion) attracted 50 percent of the estimated $1.1 billion funding to African startups in 2018, according to Partech.

Startups building financial technologies for Africa’s 1.2 billion population have gained the attention of investors. As a sector, fintech (or financial inclusion) attracted 50 percent of the estimated $1.1 billion funding to African startups in 2018, according to Partech.

Branch’s recent round and plans to add countries internationally also tracks a trend of fintech-related products growing in Africa, then expanding outward. This includes M-Pesa, which generated big numbers in Kenya before operating in 10 countries around the world. Nigerian payments startup Paga announced its pending expansion in Asia and Mexico late last year. And payment services such as Kenya’s SimbaPay have also connected to global networks like China’s WeChat.

Powered by WPeMatico

Reliable pick and place systems have long been a kind of Holy Grail among industrial robotics. The job of moving products in and out of bins is high among the jobs that many warehouse and fulfillment centers are looking to automate.

For a few years now, RightHand Robotics has been one of the more exciting startups in the space. The company has managed to drum up $34 million in funding from investors like Menlo Ventures, GV and Playground Global. This week at the ProMat conference in Chicago, the company unveiled RightPick2, the second generation of its piece-picking solution.

The news comes as the company notes that the previous version of its platform has crossed the 10 million pick threshold. This latest version features a number of upgrades on both the hardware and software fronts.

That list includes the fifth generation of the industrial gripper, which is capable of lifting up to 2 kg, coupled with new depth-sensing cameras from Intel and an improved arm from Universal Robots. That’s coupled with improvements to the system’s RightPick.AI vision/motion control software.

The results, as evidenced in the above demo, are pretty impressive. The system is speedy, fluid and capable of picking up a versatile array of different products, while capturing barcodes for order fulfillment in the process.

Powered by WPeMatico

Three million dollars. That’s the largest amount of money I’ve ever walked away from in terms of a customer contract that I decided we shouldn’t take.

It sucked. It was, at the time, more than half of the total amount of funds we had raised and it also represented just a shade more than the previous year’s revenue. It was a Fortune 500 company and the market leader in their industry. This was pocket money to them — which was part of the problem.

Good entrepreneurs spend a lot of time worrying about customers. We worry about the customers we have, the ones we don’t have, the ones we lost, and the ones we’re in danger of losing. We worry so much about where the next customer is going to come from that we never think twice about whether we should take on, or keep, a customer that’s more trouble than they’re worth.

As entrepreneurs, we need to be unflinchingly customer-first. We are the drivers, but the customers are holding the map. We should spend copious amounts of time listening, usually through data, to figure out our next move. We should know the risks when we go off-road, not only the setbacks that come with making the wrong choice, but the fact that we’ll hear about it from all sides until we right the ship.

Powered by WPeMatico

Klaviyo, a Boston-based email marketing firm founded in 2012, went about building its email marketing business the old-fashioned way. First it built a profitable company, then it went looking for funding to accelerate the growth. Today, it announced a massive $150 million Series B with the entire sum coming from Summit Partners.

The company had raised just $8.5 million before today’s announcement. Co-founder Andrew Bialecki wrote in a blog post announcing the funding that they decided to bootstrap for the first several years because they felt it was the right way to build a business — that, and they had no idea how to raise money.

“We came from families that started small businesses from scratch and ran them for decades. They may not have been huge, but they were real, lasting businesses. We wanted to try to build something like that. The second reason is much less idealistic. We had no idea how to raise money,” he wrote in the blog post.

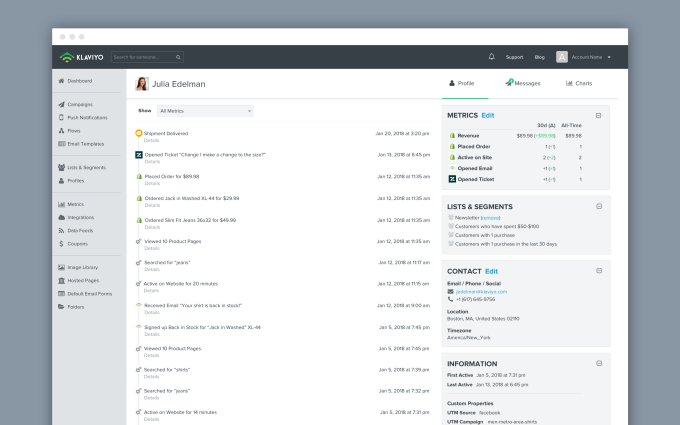

What is the company doing to warrant such a huge investment? It has created an email marketing platform, which in and of itself is not that special, but what the company has done that it feels is different is build a platform where the data lives with the messaging. This enables them to build highly customized messages quickly.

Screenshot: Klaviyo

Bialecki says there are two problems with email marketing tools today. The first is they aren’t really very smart. Most companies are still sending the same message to everyone, regardless of whether they are a new customer or a repeat one. Secondly, while they are probably measuring things like open rates and click-through rates, most platforms aren’t measuring the most important metric of all, and that’s revenue generated as a result of the email campaign.

To be fair, many companies are building highly customized email marketing campaigns based on analytics. In fact, he admits that many people ask if this isn’t a solved problem. Clearly, there are many companies selling email marketing solutions, but he says his company’s approach is different. “Our point of view is that there’s a ton of noise about this, a lot of marketing about marketing companies saying they solve these problems, but they don’t actually,” he said.

He believes the reason for that is simple. “They just don’t store all the customer data themselves. They delegate that job to data warehouses, customer data platforms or some other [platforms]. Then they try to connect them up and it’s a really bad experience.”

He said having all the data stored on the company’s platform lets their users respond much more quickly to changing situations and to deliver email that’s more personalized and in context of the user’s actual experience.

Michael Medici, a managing director at Summit Partners, who is joining the company board as part of this investment, says the company is a combination of product vision and technical expertise. “Klaviyo continues to change the playing field in commerce, allowing companies of all sizes to harness the power of data-driven customer engagement activity to grow sales – and the results are impressive,” he said in a statement.

The company is growing in leaps and bounds. It currently has 12,000 customers. To put that into perspective, it had just 1,000 at the end of 2016 and 5,000 at the end of 2017.

The company certainly understands that marketing is just one channel, but the goal up until now was to concentrate on email marketing, and get that right. Moving forward with the big investment, the company can accelerate growth and expand the platform into other areas like mobile and websites.

“We think the big change coming is to own all of those channels. Right now, businesses are forced to choose between going through some intermediary like Google or Facebook for ads, or selling on a marketplace like Amazon. If you’re a consumer business, we think you can go directly to customers,” he said.

He adds, “Our mentality is that we’re going to be a self-sustaining business, and we want to be here for decades.” With this kind of money, it certainly has the runway to be around for the foreseeable future.

Powered by WPeMatico

Just five months after announcing £85 million in Series E funding, Monzo is already gearing up to raise additional funding, which would almost double its valuation.

As reported in the Sunday Times yesterday, the U.K. challenger bank is close to raising £100 million in further funding in a new round led by an unnamed U.S. investor. If the deal goes through, it will reportedly give Monzo a pre-money valuation of close to £2 billion, up from £1 billion in October.

Now TechCrunch has learned that the new U.S. backer is Y Combinator.

According to multiple sources within investor circles on both sides of the pond, the Silicon Valley accelerator and venture capital fund plans to invest in Monzo out of its growth fund, the vehicle it typically uses to double down on fast-growing companies within its alumni.

Notably, Monzo isn’t a graduate of YC. However, Monzo co-founder Tom Blomfield’s previous startup, the payments company GoCardless, did go through the accelerator program, making Blomfield himself an alumni.

Monzo declined to comment. Y Combinator couldn’t be reached at the time of publication and I’ll update this post should I hear back.

Meanwhile, the news that Y Combinator is lining up to invest in Monzo makes a lot of sense in a number of ways beyond Blomfield’s previous ties to the accelerator. The challenger bank already boasts a plethora of U.S. investors, such as U.S. venture capital firm General Catalyst, Thrive Capital and Stripe.

And, as TechCrunch reported exclusively, Monzo has quietly begun working on a U.S. launch. This includes setting up a small team states-side to begin laying the groundwork to bring a version of Monzo to North America. It will initially be powered by a U.S. banking partner while Monzo works on the necessary regulatory licenses to go it alone.

Monzo continues to grow at a clip here in the U.K., too. To date, the challenger bank claims more than 1.7 million customers since it launched in 2015.

Powered by WPeMatico

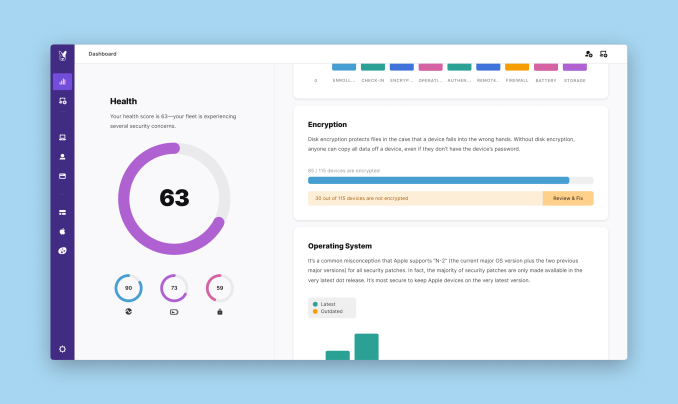

Fleetsmith launched in 2016 with a mission to manage Apple devices in the cloud. It simplified an IT activity that had previously been complex, with help from Apple’s Device Enrollment Program. Over the last year, the startup has beefed up its offering considerably, and today it announced a $30 million Series B round led by Menlo Ventures.

Tiger Global Management, Upfront Ventures and Harrison Metal also participated. Under the terms of the deal, Naomi Pilosof Ionita, a partner at Menlo, will join the company board. Her colleague Matt Murphy will become a board observer. With today’s announcement, the startup has now raised more than $40 million, according to data supplied by the company.

Company co-founder and CEO Zack Blum says the original mission was about solving a pain point he and his co-founders were feeling around finding a modern approach to managing Apple devices. “From a customer perspective, they can ship devices directly to their employees. The employee unwraps it, connects to Wi-Fi and the device is enrolled automatically in Fleetsmith,” Blum explained.

He says that this automated approach, combined with the product’s security and intelligence capabilities, means that IT doesn’t have to worry about devices being registered and up-to-date, regardless of where an employee happens to be in the world.

It has moved from solving that problem for SMBs to having a broader mission for companies of all sizes, especially those with distributed work forces, which can benefit from enrolling in this automated fashion from anywhere. Once enrolled, companies can push security updates to all of the company’s employees and force updates if desired (or at least send strong reminders to avoid updating in the middle of a client meeting).

Over the last year, the company developed a dashboard for IT to monitor all of the devices under its management, including providing an overall health score with any potential problems it has found. For example, there may be a number of MacBook Pros without disk encryption enabled.

The dashboard ties into the identity management component of Office 365 and G Suite. IT can import the employee directory into the dashboard from either tool, and employees can sign into Fleetsmith with either set of credentials, providing a quick way to manage all employees in an organization.

Screenshot: Fleetsmith

Fleetsmith has also set up a partner program with Managed Service Providers (MSPs) to expand its reach further. MSPs manage IT for SMBs, and building a relationship with these types of companies can help it expand much more quickly.

The approach seems to be working, as the company has 30 employees and 1,500 customers. With the new cash in pocket, it intends to hire more people and continue building out the product’s capabilities, while expanding beyond the U.S. to markets overseas.

Powered by WPeMatico

Extra Crunch offers members the opportunity to tune into conference calls led and moderated by the TechCrunch writers you read every day. This week, TechCrunch’s Kirsten Korosec and Kate Clark led a deep-dive discussion into Lyft’s IPO and the outlook for the business going forward.

After skyrocketing nearly 10% on its first day hitting the public markets, Lyft stock has faded back down towards its IPO price as some investors grow more concerned over the company’s path to profitability (or lack thereof) and the long-term fundamentals of the business. But Lyft’s public listing is bigger than just the latest in increasingly common unicorn IPOs. As the first public “transportation-as-a-service” company, Lyft offers the first inside glimpse into the business model and its economics, and its development may ultimately act as the canary in the coal mine for the future of transportation.

“Lyft, hasn’t just survived, they’ve grown. 18.6 million people took at least one ride in the last quarter of 2018. That’s up from 16.6 million in late-2016. That illustrates the growth that the company has had. They’ve also said that they have 39% share of the ride-sharing market in the US. That’s up from 22% in 2016.

To me, the big question is let’s say they had Uber’s share, which is 66%, would they be able to make a profit? Is that the determination? And I’m not convinced that it is, which is why all these other aspects of the transportation-as-a-service business model [micromobility, AVs, etc.] are going to be really important.”

Image via Getty Images / Mario Tama

Kirsten and Kate dive deeper into what the market response to Lyft means for Uber and the timeline for its impending IPO. The two also elaborate on their skepticism of ride-hailing economics and debate which innovative transportation model will ultimately drive the path to profitability for Lyft, Uber and others.

For access to the full transcription and the call audio, and for the opportunity to participate in future conference calls, become a member of Extra Crunch. Learn more and try it for free.

Danny Crichton: Good afternoon and good morning everyone this is Danny Crichton, executive editor of Extra Crunch. Thanks so much for joining us today with TechCrunch reporters Kate and Kirsten.

I’ll start with a quick introduction for our two writers today. We have Kate Clark, our venture capital reporter. Kate has been with us for a while now covering everything in the startup and venture world. She’s also one of the hosts of TechCrunch’s podcast Equity and also writes our Startups Weekly newsletter.

Our other writer today is Kirsten, our intrepid automotive writer covering all things Elon Musk, Tesla, and everything else in the autonomous vehicle space. Kirsten has also been with us for quite some time and also writes a newsletter that she just introduced in the last couple of weeks, around transportation. So with that, I’m going to hand off the conversation to the two of them now.

Kirsten Korosec: Thanks so much Danny. This is Kirsten Korosec here. The newsletter is in a bit of a soft launch but it is being published Fridays and we hope to have an email subscription coming sometime in the future, so just keep an eye out for that.

I should also mention I too have a podcast centered around autonomous vehicles and future transportation called The Autonocast that comes out weekly. Thanks so much for joining the call and just a reminder, we want participation. So at about the halfway point, we’ll turn and open up the line and answer questions. Let’s get started.

Before we dig into all the hot takes out there, I think it’s worth providing a primer of sorts — a general timeline of events. We all probably know Lyft of course and most of us think of 2012 as the launch date when it came to San Francisco, but really Lyft was build out of the service of Zimride. Which is the ride-sharing company that John Zimmer and Logan Green founded in 2007.

A lot of attention has been placed on Lyft in 2018 with what happened in the past year, in the run-up to the IPO. But I think it is worth noting the intense activity and growth that happened between 2014 and 2016. These are critically important years for Lyft, just a frenzy of activity in a period where the company gained ground, investors, and partners.

To showcase the amount of activity that was happening; Lyft had two separate funding rounds, one for $530 million another for $150 million, just two months apart in 2015. You might also recall in early-2016 its partnership with GM and the automakers’ $500 million dollar investment as part of the Series F $1 billion dollar fundraising effort.

That was really interesting because GM’s president at the time Dan Ammann took a seat on the board, which he has since vacated. As Lyft and GM started realizing that they were competitors. Now, Dan is the CEO of GM Cruise which is the self-driving unit of GM.

2017 and 2018 were also big years, as Lyft launched their first international market in Toronto. They made big moves on the autonomous vehicle front, which we’ll talk about today, and in micromobility. Their scooter business launched in Denver in 2018. They bought Motivate, which is the oldest and largest electric bike share company in North America. Then, we finally get to the end of 2018, and this is when Lyft confidentially files a statement with the FDC and we’re off with the races to the IPO.

The last two months or three months is when Lyft unveiled its prospectus, met with investors, priced its IPO and made its public debut. So Kate what are the nuts and bolts of the IPO and what’s happening right now?

Kate Clark: Hi everybody this is Kate. So I’m just going to mention really quickly the timeline these last couple of months in the run-up to Lyft’s highly historical IPO. So going back to December, that’s when Lyft initially filed confidentially to go public. We later find out that they are going public on the NASDAQ when they eventually unveiled their S1 in early March.

This is after Lyft had raised $5 billion in debt and equity funding at a $15 billion dollar valuation, so there are a lot of people paying attention to what was the first ever rideshare IPO. So then in early-March, we’re able to get a closer look at Lyft’s S1, which tells us that the company has $911 million in losses in 2018 and revenues of $2.2 billion. So after calculating and pulling together some data, a lot of people were quick to find out that that means Lyft has some of the largest losses ever for any IPO. But also has some of the largest revenues ever for any pre-IPO company, just following Google and Facebook in that category.

So this is a really interesting IPO for a lot of people given these sky-high losses but also these huge, huge revenues. The next we see Lyft price their IPO between $62 and $68 dollars a share. Some people were quick to say that that was maybe a little underpriced, given that this was a highly anticipated IPO with a ton of demand. So on the second day of Lyft’s roadshow, the process, they say that their IPO is oversubscribed. So demand is apparently huge, their oversubscribed, so they decide we’re going to increase the price of our shares.

Image via GettyImages / maybefalse

So Lyft then says they gonna charge a max of $72 per share and then on the day of their IPO they charge $72 per share, the next day opening at $87 per share. So we see a huge IPO pop that I don’t think was particularly surprising given that they already spoke of this demand, and we had already known that there was a lot of demand on Wall Street. Not just for Lyft but just for unicorn IPO’s of this stature, given that there are so few of these. So Lyft began trading hitting $87 per share though, if you’ve been following the news that’s not were Lyft is today.

Kirsten: Yeah so I was just about to ask — Kate give me the latest numbers, you know a lot of focus is on that opening day but things haven’t exactly sustained. So what’s happened in the past few days?

Kate: Yeah it’s really tough to manage expectations after an IPO. I mean, I think there has been a lot of criticism towards Lyft now and I think it’s trading below its initial share price. So as I mentioned Lyft opened at $87 per share, it priced at $72, but almost immediately they began trading below that $72 price per share. So they closed Tuesday trading at $68.96 per share. Still boasting a market cap larger than $19 billion. So they’re still significantly valued at more than they were as a private company at $15 billion but it doesn’t look good to be trading below a price per share so quickly.

However, it actually did hit its IPO price for just a minute today, so maybe let’s give it a few more hours and see where it closes. It’s possible that it will sort of jump towards that $72, but it’s still trading quite significantly below that $87.

Kirsten: With IPOs like this, and especially such a high profile one, there’s going to be a ton of attention on share price and on volatility. And so I’m wondering, in your view, what did this first week, or first few days of volatility say to you? What does it say about Lyft’s future and, well certainly, its present?

Kate: Yeah. I mean, it’s hard to say. I think a lot of people were questioning if Wall Street was going to be interested in a company like Lyft that’s extremely unprofitable at this time and has years left before it will reach profitability, if indeed it ever reaches profitability.

So at this point you got to wonder, do some of these investors that did buy Lyft right off the bat, were they really long on Lyft? Because it does look like a lot of those investors have already sold their stock and perhaps weren’t as invested in Lyft’s long-term profitability plan, which involves a lot of very iffy things, like the future of autonomous vehicles, which we’ll talk about later in this call. And there’s a lot of uncertainty there.

But with that said, it’s not uncommon for a stock to experience volatility right off the bat, and you can’t assume the future of that stock price just because of some early volatility.

And we gathered some examples of IPOs where there was some early volatility that did not determine the long term future. So Carvana, for example, which is an online used car dealer in the automotive space, and it did experience volatility at first, with the stock sliding in the first few months but ultimately trended upward.

Kate: So Carvana opened at $13.50 a share, falling below its IPO price, so it didn’t even have the IPO pop. And then in 2018, it hit an all-time high of $65 per share. Today, it’s trading around $58 per share, so that’s ultimately a positive story to be told there.

And then another example on the other side of things is Snap, which actually took four months to dip beneath its 2017 IPO price, and we all know Snap has definitely not been a success story and it’s trading well below its offer price. But then finally, Facebook, for example, dropped below its IPO price on its second day of trading and then actually had a rough first year on the stock market before the stock ultimately took off and became a very obvious success.

Kirsten: So, Kate, I’m wondering why you think that there was that initial run up on that first day. Was it excitement? Was there something material that was pushing the price up? What was the cause?

Kate: I think there was a lot of excitement and demand around this IPO because it was very much one-of-a-kind, and there were a lot of investors that it seemed were really long on the possibility of Lyft becoming this hugely profitable company. And I think a lot of that was because in the S1, although you did see these really, really big losses — quite major, just ridiculously huge losses — you did see that they were shrinking over time and that there was definitely a path in which Lyft could take where it would reach profitability, say, in the next five years.

And I think Wall Street was really paying attention to that, and they were not paying attention to some of the other metrics. Now, they’ve taken off their rose-colored glasses and they’re looking at Lyft as a public company, and it’s just a little bit different now that it’s actually completed its debut.

Kirsten: Well, so, I mean, I like to view IPOs often times, and especially in Lyft’s case, as a measure of an investors’ faith in the company’s growth prospects, because this is a company that while it does have quite a bit of revenue, it has significant losses and it’s really planning not just for the present day but for the future. It’s been called a disruptive business for a reason, and it is certainly very forward-looking. So I’m wondering if you think it was a good strategy for Lyft. They wanted to open it up to “the everyman” when they actually went to market. They did a different approach, and do you think this might have had an effect? I mean, it’s very on-brand for them to do this, but I’m wondering if you thought that means that some of the investors aren’t as disciplined.

Kate: Do you mean with the fact they were providing bonuses to their employees and drivers to actually participate in the IPO as well?

Kirsten: Absolutely. That’s actually a really good point that maybe you can elaborate on. Lyft did a little bit of a more open approach for its IPO. Typically IPOs can be closed off to only large, institutional investors. So did this set them up perhaps to have more volatility?

Kate: Yeah, Lyft provided some of their drivers up to, I think, $10,000 to, in theory, actually buy stock in the IPO. Do I think that had a high impact? I don’t know. I think there’s not enough comparison, not enough data to really make a decision or to make a hot take on whether that really was part of the volatility. I think just given the uncertain nature of Lyft’s future and their big losses, I think their volatility was pretty inevitable, and I think people paying attention to this are probably not particularly surprised by how the stock has fared in these first couple days.

And I do want to add there’s this six-month lock-up period for the venture capital funds that own Lyft and as well as their employees, so I think we’re not sure what’s going to happen when that lock-up period ends and those holders can just sell their stock right then or how that will impact the stock price, as well.

Image via TechCrunch/MRD

Kirsten: So something to keep an eye on. It reminds me a lot of a company I write a lot about, which is Tesla, and I’ve been covering them for years. And it’s one of the most volatile stocks, and their investors, they certainly have large, institutional investors, but the number of fanboys that they have with smaller investors, either prop up the share price sometimes or add to that volatility, and I’m kind of really curious to see if that happens with Lyft. If you go to a shareholder meeting at Tesla, for example, it’s filled with people who are passionate about the brand and its CEO, Elon Musk.

And Lyft and possibly Uber, if they end up finally going through with their IPO, you can see that potentially happening because people feel very strongly about the brand and also the service it provides. So I’m curious to see how this all sort of shakes out. And I tend to take the view that I invest personally in mutual funds and things like that. I don’t invest in any of these companies, but the long, patient view tends to be the better one, and trying to catch a falling knife, as investors have told me, is never really a good idea.

So I’m curious to see if investors sort of grow up and learn with Lyft, if they’ll become disciplined and just sort of wait it out and see them play out the growth prospects for the company in the long term. So, we’ve been talking about Lyft and I can’t not talk about Uber as a result. I’m wondering what you think this might mean for Uber. The big story initially was let’s beat Uber to IPO and I’m wondering what this means then. Is this indicative of what Uber is going to experience?

Kate: I think that question is really at the top of everyone’s mind right now, including my own. I will say that I still do think it was highly beneficial for Lyft to get out first. Because imagine if and when Uber does too experience volatility, which it probably will, if it were to have gone first, I think that would have frightened Lyft a lot more than Lyft’s volatility may or may not be frightening Uber. So, with that said, I think I’m of two minds right now with my thoughts on how this impacts Uber’s IPO. I think that if Lyft stock continues to be volatile and perhaps even falls lower than it already has. I do think that there is a chance Uber may ultimately decide to push its IPO back.

I think that for a few reasons, namely being that Uber is not in a huge rush to go public. They do have the ability to wait. They have filed to go public. So it’s likely to happen quite soon, but it may not happen in April as they are reportedly planning to do.

On the other hand, Lyft went public at like a $24 or $25 billion dollar market cap. Whereas Uber is going to debut at maybe a $120 billion dollar initial market cap. So these IPOs, although they are both ride hail IPOs and they are very similar companies in a lot of ways, they’re also very different and Uber is operating on an entirely different scale though it still is unprofitable. And has some of the same issues that, investors are probably noting about Lyft.

I think it’s either going to be that it’s maybe that they do decide to push it back or maybe that Uber is like, well we’re five times larger, six times larger. We have much larger statistics to show to investors. There’s just a chance it could go either way. I wish I had a better, more concrete answer, but I just don’t think we know yet.

Kirsten: Well I’m okay with not taking hot takes just a few days into this IPO. I think this is a good time to open it up to questions. While we wait for a question, I will do one quick follow up with you Kate. What do you think this means for Uber? Will it delay its IPO?

Kate: Right now, no, I don’t think they’re going to. But it’s like I said, it’s tough to say given that it’s only been a few days of Lyfts IPO. But no, I think you’ve got to imagine that they are ready to discuss the possibilities of Lyfts IPO and already planned ahead if there was volatility. They maybe already assumed that would happen, given that that’s not uncommon. So right now I’m going to say no, I don’t think they’re going to delay, but it’s certainly still a possibility.

Kirsten: Okay, great. I think another really interesting piece for Uber was their acquisition of Careem. This is a deal that was made right before their IPO, so it was shifting attention away from Lyft, just for a moment.

Why did Uber do this? Is this not a signal that they’re delaying their IPO? Is this just prepping for it? What are you hearing on it? I’m wondering if this might have just been a strategy to show the world investors, specifically potential shareholders, what the road ahead is going to look like. Or is it some other reason — Is it to justify their really big losses?

Image via Careem / Facebook

Kate: I think it’s the latter two things you said. Just to give some background Uber is paying about $3.1 billion to acquire Careem, which is a Middle Eastern ride-hailing company. So basically just the Uber of the Middle East. Uber does have a history of acquiring, smaller competitors like this in different markets where it’s not active, just as a way for Uber to quickly grow essentially.

So I do think it’s a big deal to make just before going public. So I guess we don’t know if they necessarily will go public in April, but I think it was a move to present to public market investors as a prep for an IPO, to show “we just acquired this company, here’s more evidence of future growth”. Like you mentioned, it’s definitely a justification of those huge losses that we know Uber has.

Kirsten: Thanks for that. Questions?

Caller Question: Hi there, so when we talk about looking ahead and moving towards profitability — what role, if any, do you think the acquisition of a scooter or other mobility companies will have for companies like Lyft and Uber?

Kirsten: That’s a great question. I think it’s going to be a huge piece of both of their businesses. A lot of people describe this as the first ride-hailing IPO. We need to stop calling this a ride-hailing company. These are transportation-as-a-service companies and they’re making money. But generating revenue as opposed to making profit is a totally different thing. When you start talking about ridesharing, it’s a tough business. With those it’s an asset-light business, right? They don’t own the cars and then they technically don’t employ these drivers.

But at the same time, as of 2016 only something like 1% of people in the US were using rideshare. So you see this opportunity, but they’re not pushing forward. There is a ton of car ownership still that’s happening. Yes, sharing has absolutely increased, but 17 million new cars were sold in the US last year. So scooters, bike share and other businesses are going to be key to their paths to profitability because ride-sharing alone is just difficult to make a profit. It’s not difficult to generate revenue. It’s difficult to make a profit on.

And I’m wondering, talking about that road to profitability, I do think it’s worth noting how much they have grown. Lyft, hasn’t just survived, they’ve grown. 18.6 million people took at least one ride in the last quarter of 2018. That’s up from 16.6 million in late 2016, that illustrates the growth that the company has had.

They’ve also said that they have 39% share of the ride-sharing market in the US. That’s up from 22% in 2016. To me, the big question is let’s say they had Uber’s share, which is 66%, would they be able to make a profit? Is that the determination? And I’m not convinced that it is, which is why all these other aspects of the transportation-as-a-service business model are going to be really important.

Kate: I think what you pointed out is important, about Lyft and Uber both becoming transportation businesses, not ride-hailing companies and I think their long-term visions involve scooters, bikes, autonomous vehicles, all sorts of different models of transportation beyond just car sharing.

Kirsten: I hate to be wishy-washy here and say, I don’t know, but I do really think that it’s going to come down to a variety of items all coming together. It’s just not going to be enough for Lyft to scale up its ride-hailing business. And I should point out that Uber should be treated in some ways the same way, but there are some distinct differences. But it’s important for us to think of Lyft as a transportation-as-a-service business. I mean they say in their prospectus that transportation is a massive market opportunity. The hard part of course is turning that into a profit. There might be opportunity there.

So there’s this asset-light business that they have right now, which is the ride-hailing, but then they are making acquisitions in the micromobility space and that is going to become more capital intensive. And that’s going to force them to change their business. And then there’s the autonomous vehicle piece. And then finally, I actually think that one of the pieces of their S1 that has really not received much attention at all is what they’re pursuing in terms of public transportation. And they have said that they, and Uber, intend on being a piece of the public transit ecosystem.

Now that doesn’t mean that they’re going to necessarily be operating buses, but there are people that I’ve talked to in the industry who actually feel like, in Uber’s case, they want to control every mode of transportation. For Lyft, I see them seeing more of the opportunity financially with the data piece and becoming more of a platform and becoming that one-stop shop where you use an app to figure out if you want to use the scooter or a bike, or ride-hailing or buy that ticket for the L in Chicago or the Bart System.

So I really think that the public transit piece often gets ignored and cities are having so much more control now and weighing in. We see this in New York City with congestion pricing. It’s going to force Lyft and Uber to take advantage of these opportunities and use their platform in a way that perhaps accelerates faster than they had intended.

Kate: I’m very interested in the public transportation element, but I’m also very skeptical of the scooters and bikes in the future for Lyft, I think, given the unit economics, I certainly wouldn’t rely on them to be Lyft’s path to profitability. I think autonomous vehicles are a much more interesting path towards profitability. So a lot of companies, Uber, Lyft, Waymo and more are focusing on autonomous vehicles and their development, whether that be with hardware or software. How does Lyft’s strategy with autonomous vehicles differentiate from some of their competitors or does it does differentiate?

Kirsten: It does differentiate, and the funny thing is, is that so you don’t see micromobility necessarily as the oath to profitability and are interested in AVs and I write about AVs, but I see that AVs as a harder path to profitability in a way because of the nuts and bolts that it takes to develop them.

So just to weigh in really quickly on the micromobility piece and then I’ll move on to AVs; To show the opportunity but also the volatility in a real-world example for micromobility, I was in Austin for South by Southwest, I think you were there too, and you probably saw scooters everywhere, right? 18 months ago there were no scooters or bike share in the city. Then bike share came first.

Image via Flickr / Austin Transportation / https://www.flickr.com/photos/austinmobility/41536051644/in/album-72157669223418248/

And I was talking to that mayor of Austin and one of the folks from Spin, which is a Ford owned business, and they told me something that was really remarkable that I hadn’t thought about, which was that scooters were disrupting the bike share business. So bikes share came in and then scooters came in and all of a sudden they’re pulling bikes off the streets because no one was using them or were not using them at the same level as scooters.

Lyft is going to go through these same exact growing pains and people are figuring out what works. And as you mentioned, the unit economics are an issue, the wear and tear on the scooters alone is driving up costs and driving down revenues certainly, but pretty much making it very difficult to make a profit on it.

But that’s a near term business, right? So it’s at least generating revenue right now. On the other hand, you have this other piece, which is the AV piece. Lyft is doing some really interesting things on the AV piece — they kind of have a two-prong approach.

So they basically created a ton of partnerships to use their platform. So this started a couple of years ago and companies like Aptiv, drive.ai, even Waymo and nuTtonomy, which Aptiv just recently bought about a year ago and GM, and Lyft basically allows developers to use their platform and connect to their autonomous vehicle and offer these rides.

And the best example of this, if you’ve been to CES or if you have been to Las Vegas I should say more specifically, is this partnership that Lyft has with Aptiv — and Aptiv as a tier one supplier, they used to be called Delphi, they spun out, they bought nuTonomy, and they’re Aptiv now. And this is taking Aptiv automated BMW, which are on the Lyft network. If you hail a ride, you might be asked if you want a self-driving car, or “are you okay with a self-driving car?” And they have a safety driver, no humans have been pulled away from it yet. But they provided about 35,000 rides since I want to say January 2018.

Then they’re also doing Level 5, a dedicated self-driving vehicle division that launched in 2017. And here they’re basically creating an open self-driving system or open SDS. On top of that, they have partnered with Magna, an auto parts producer, to develop these self-driving systems that can be manufactured at scale.

And so you just see a rush of partnerships and sort of dual approaches and all of that costs a lot of money. And I can’t emphasize the amount of money that it costs or will cost to develop these systems and deploy them commercially. And I hear from other companies figures like $5 billion to get self-driving vehicles. So developing the full stack, doing fleet management, maintenance, all of that — that’s a lot of money. And, I’m not sure where Lyft, will get that capital, will they get it from the open market or will they have to go and ask for more capital.

Kate: So when do you think then that Lyft will be able to commercialize autonomous vehicles?

Kirsten: The timeline? So depending on who you talk to, you can hear from any of these developers between five years and 30 years. I think it’s important to talk about language and how we talk about autonomous vehicles. So to be clear, there is currently not a single commercial autonomous vehicle deployment where a human being or safety driver has been pulled away from the wheel. It just doesn’t exist.

There are plenty of pilots and Waymo is probably considered the leader in that list, though it is a bit of a confusing one for me because they have so many partnerships and they’ve become competitors to some of those partnerships. The analogy I use is “Survivor,” the reality show. Everyone wants to make these alliances so they don’t get voted off the island.

And now we’re at that point where autonomous vehicle development has entered what we call the trough of disillusionment, which is heads down, “let’s get away from the hype, let’s do the hard work.” And I think we’re going to see a lot of those partnerships and headwinds really come up in the next year, 18 months. So to put a target date on Lyft, it’s really going to depend on which one of those partnerships really play out and are real. I think the one with Aptiv seems the most real to me based on what I know the company is doing and I can see them doing a lot more pilots in the next 18 months.

Does that mean commercial deployment without a human safety driver behind the wheel? I’m not sure I can see a lot more these pilots with a human safety driver expanding beyond Las Vegas. I see pilots happening absolutely in the next year to 18 months. The issue is going to be when is that human safety driver going to be pulled out and with which partner.

Kate: So should we open it up to questions again?

Caller Question: Hi, I was just wondering how we should think about the regulatory risks that might exist as these companies expand to new cities, new markets, or even the public transport use case you mentioned. Thanks.

Kirsten: The regulatory piece is an interesting one. Let’s talk about ride-hailing first. We’ve already seen the regulatory environment, in cities, push back against companies like Uber and Lyft. I think the congestion pricing model that just launched in New York City is going to be one to watch and could be something that will put pressure on, on businesses like Lyft.

Kate: I agree and just to speak, quickly on the scooters; I think the narrative around scooters has been pretty dominated by how cities have forced them out or cities push these strict regulatory barriers on them. And I think that’s still playing out very much. There are even some scooter providers that have had to pull out of cities that they worked very hard to get into in the first place. So I think that has slowed down some of the growth there. And given that Lyft has micromobility as such a key part of their road to profitability, I think that’s partially why I am a little bit skeptical of how that’s gonna play out.

Kirsten: One thing we’ve found, and something to consider for Uber as well, in the future, if any of these AV developers end up, filing for IPOs on their own — there’s been chit chat about Waymo someday doing that or GM cruise someday— the implications for all of these companies and their relationship with cities should not be ignored or undervalued.

And I think you see a bit of that playing out with the present day track we have, which is the ride-hailing scooters and bike share cities and transit agencies or the DOT of different counties finding that they are in a more powerful position than they’ve ever been before. And they are exerting that power.

And so you will see instances like Los Angeles where they have put forth a mandatory data sharing component if you want to operate in their city. This raises some privacy concerns by the way, but it also adds another cost to a company or certainly forces them to look at their business a little bit differently.

Then you start talking about AVs and where are they will operate, how they will operate, where are they will park, what type of vehicle will be allowed in the urban center. In places like Europe, there are strict emissions rules, so that’s going to go to an AV or hybrid profile. And it’s important to think about what that regulatory framework might be and acknowledge the fact that it’s really a mishmash.

There are voluntary guidelines on the federal level right now, but there were no mandates. And so it’s really left up to the cities, counties and states to decide how an AV might be deployed. It’s going to mean probably more lobbyists in DC working with federal folks to ensure that their business doesn’t get hamstrung as a result as well as more of a presence in those cities and states and counties.

But Kate, I’m wondering what is your view from a startup perspective? Do you think of Lyft as a startup anymore are they acting like a startup or are they acting like a company that could handle all of these different complicated, various challenges? I mean, we’ve got pricing pressure, regulatory pressure or you’ve got AV development, opportunities with scooters and all this other stuff. So are they acting like a company that is able to handle this?

Image via Getty Images / Jeff Swensen

Kate: That’s an interesting question. I mean, they’re definitely not a startup anymore by, by anybody’s definition. You maybe could have still used that word, if they were still private, but even then, I know many people would yell at you for using that term for a company worth $15 billion. But now it’s a public company. It’s not a startup. I don’t think they’re acting like a startup, no. I think that they are mature in the way that they’re handling all of these different, so-called paths to profitability.

But we need to wait and see. Let’s see how this year goes, let’s see how they handle all the criticism that they’re going to undoubtedly take from Wall Street or from everyone who’s either interested in buying or just taking a seat and watching how the stock favors and then we’ll know what kind of lessons they took from all those years as a private company. Then we can decide if their behavior is really that of a mature public company.

Kirsten: I do want to make one point that I think is an interesting one on Lyft’s strategy versus Uber is in terms of AVs. Let’s all put a big asterisk that says no, AVs are still a ways out. It is important to note the Lyft and Uber’s strategies for AVs are wildly different and Uber does not take this dual approach. Uber is throwing a ton of capital towards developing their own, self-driving stack and also they’ve done, some acquisitions as well.

They’ve also had quite a bit of trouble. Last year Uber had the first self-driving vehicle fatality that happened in Tempe, Arizona, which looked like it was going to derail their self-driving unit, but it did not. They’re back, testing in a very limited way, but Lyft’s is all about what they call the democratization of autonomous vehicles.

And we can look at that as marketing speech, but I do think that it’s important to look at those words because it shows what their business model is. Their business model is partnerships, alliances, opening up the platform and casting the widest net possible. What I’m very interested to find out is which approach will end up being the winner. It’s going to be a very long game. It’s not going to be anything that’s going to be determined in the next year. I think what Lyft’s proven is that when they look like they’re down and out, they come back.

We’ll see what the better approach is. Do you do everything in-house and launch your own robo-taxi service? Or take capital partners on or do the Lyft approach, with multiple partners? Are partnerships actually too complicated? As someone who covers the startup world, do you have a thought on which one might work or not?

Kate: I have no idea which will work better and I’m sort of excited to see where this all goes, especially as Uber and Lyft are now going to be public.

That’s a good spot to end the call on.

Kirsten: Thanks so much for joining. Thanks again for being Extra Crunch subscribers, we really appreciate it. Bye everyone.

Powered by WPeMatico

Let’s start this week’s newsletter with some data. Nationally, startups pulled in $30.8 billion in the first quarter of 2019, up 22 percent year-on-year, according to Crunchbase’s latest deal round-up.

A closer look at the numbers shows a big drop in angel funding and a slight decrease in mega-rounds, or financings larger than $100 million. The number of mega-rounds fell to 57 deals in Q1 and deal value was down too. With that said, mega-rounds still accounted for $16.4 billion, making Q1 2019 the second-best quarter on record for mega-rounds.

The bottom line is these monstrous deals represented a big chunk (29 percent) of all the dollars invested in U.S. startups in Q1. As investors move downstream and startups opt to stay private longer and longer, we’ll continue to see a greater pick up in mega rounds.

Want more TechCrunch newsletters? Sign up here.

OK, on to other news…

Once trading after the pink confetti was swept up off the floor, analysts and investors had a different story to tell about one of the first unicorns to make its public debut. Lyft began the week struggling to hit its IPO price, closing several days under that $72, despite opening with a 20 percent pop at $86. What’s going on? People are shorting the Lyft stock, looking to profit off the company’s sinking value. Things are looking up though; on Friday as I typed this newsletter, Lyft was trading at about $74 per share.

.@Uber sent @Lyft a whole bunch of cakes on IPO day, how nice. pic.twitter.com/hbZC5HOxbL

— Kate Clark (@KateClarkTweets) April 5, 2019

In other IPO, or shall I say, direct listing news, Slack has reportedly chosen the NYSE for its upcoming exit. A quick reminder why Slack has opted to go public via direct listing: The company doesn’t need any IPO cash thanks to the hundreds of millions of dollars on its balance sheet, but its longtime employees and investors need the liquidity. A direct listing allows it to go public without listing any new shares, with no lockup period and no intermediary bankers. The process saves it some money and expedites the process. OK, that wasn’t as brief as I intended, moving on…

Saying goodbye to venture capital

In a story that sent the entirety of Silicon Valley into a frenzy, Forbes reported that Andreessen Horowitz was denouncing its status as a venture capital firm and would register all its employees as financial advisors. For those inclined, Crunchbase News’ Alex Wilhelm and I unpacked what this means in the latest episode of Equity; for those less inclined, here’s the TLDR: For a16z to have the freedom to make riskier bets, like buying public company stock or heaps of cryptocurrency, the title of financial advisor gives them that ability.

Femtech, defined as any software, diagnostics, products and services that leverage technology to improve women’s health, has attracted some $250 million in VC funding so far this year, according to PitchBook. That puts the sector on pace to secure nearly $1 billion in investment by year-end, greatly surpassing last year’s record of $650 million. For more historical context, startups in the space brought in only $62 million in 2012, $225 million in 2014 and $231 million in 2016.

Alternative financier Clearbanc says it will invest $1 billion in 2,000 e-commerce startups in 2019. Here’s the catch: Until the companies have paid back 106 percent of Clearbanc’s investment, Clearbanc takes a percentage of their revenues every month. Clearbanc’s goal is to help companies preserve equity, favoring a revenue share model rather than the traditional VC model, which eats equity in startups in exchange for capital. I spoke to Clearbanc co-founder Michele Romanow to learn more about Clearbanc’s attempt to disrupt venture capital.

TechCrunch’s Megan Rose Dickey authored the be-all-end-all story on the shared-electric-scooter business. Here’s a quick passage: “The startup ecosystem had become accustomed to the ethos of begging for forgiveness, rather than asking for permission. But that’s not the case with electric scooters. These companies have found their entire businesses to be contingent on the continued approval from individual cities all over the world. That inherently creates a number of potential conflicts.” Extra Crunch subscribers can read the full story here.

Plus, we dropped the Niantic EC-1, in which Greg Kumparak dives deep into the history of the maker Pokemon Go, contributor Sherwood Morrison looked at remote workers and nomads, who represent the next tech hub.

TechCrunch has confirmed that Airbnb has invested between $150 million to $200 million in Indian hotel startup Oyo. Airbnb confirmed the existence of the deal but not the exact amount. The home-sharing giant is continuing to widen its focus beyond “unconventional” hotels as it prepares to begin selling pubic market investors on its long-term vision. Remember, this deal comes right after its big acquisition of HotelTonight.

WeWork acquired Managed by Q this week, a VC-backed startup that helps office managers and other decision-makers handle supply stocking, cleaning, IT support and other non-work related tasks in the office by simply using the Managed by Q dashboard. The company was most recently valued at $250 million, having raised a total of $128.25 million from investors such as GV, RRE and Kapor Capital.

If you enjoy this newsletter, be sure to check out TechCrunch’s venture-focused podcast, Equity. In this week’s episode, available here, Crunchbase News editor-in-chief Alex Wilhelm and I chat about the future of a16z, Jumia’s IPO, the Midas list and more of this week’s headlines.

Powered by WPeMatico