Startups

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Your last 10 emails with a recruiter before an onsite interview probably shouldn’t be about rebooking your canceled flight.

Pana is a Denver startup now setting its sights on the corporate travel market, with a specific eye towards killing the back-and-forth email or spreadsheet coordination. The startup, founded in 2015, first tried to gain an inroad with consumers, but its $49 per month individual-focused travel concierge plan probably limited its reach.

The company’s latest shot at taking on corporate travel lets companies use the service to outsource dealing with out-of-network “guests.” The startup is looking to take this path as an inroad into the broader corporate travel market, and is making the apparent choice to work with more expansive corporate travel companies like SAP’s Concur rather than against them, initially at least.

The company just closed a $10 million Series A round led by Bessemer Venture Partners with participation from Techstars, Matchstick Ventures, and MergeLane Fund. Previous investors also include 500 Startups, FG Angels and The Galvanize Fund.

Pana is already booking thousands of trips per month for companies using the service to coordinate business travel for interviewees. Rather than leaving recruiters to the arduous process of back-and-forth messaging to hammer out initial details, Pana takes care of it through an omni-channel mesh of automation and human concierge in-app chat, text or email.

“A key piece of the value proposition is that if you do ask something complex, we’re going to instantly connect you to a human agent,” founder Devon Tivona told TechCrunch in an interview. “When it does go to a person, we have a five-minute response time.”

Getting a flight booked for someone outside the company directory can be challenging enough, but with travel, everything grows infinitely more complex the second that something goes awry. In addition to functioning as a tool for coordination, the startup’s team of assistants are there to help re-book flights or re-arrange travel if everything doesn’t go according to plan.

Even if Pana is working with the big corporate travel agencies today, its investors are banking on the startup accomplishing what the giants can’t at their scale.

“…Whenever a really large incumbent, particularly in software gets acquired, and I’m thinking about when SAP acquired Concur five or so years ago, it creates this massive innovation gap that allows, I’d say, new startups to really reinvent the status quo,” Bessemer partner Kristina Shen told TechCrunch in an interview.

Pana’s current customers include Logitech, Quora and Shopify, among others.

Powered by WPeMatico

Seven years ago, Rachel Haurwitz finished her last day as a student in the University of California laboratory where she helped conduct some of the pioneering research on the gene editing technology known as CRISPR, and became employee number one at Caribou Biosciences, a company founded to commercialize that research.

In those seven years, the market for CRISPR applications has grown tremendously and Caribou Biosciences is at the forefront of the companies propelling it forward.

Which is why we’re absolutely thrilled to have Haurwitz join us on stage at Disrupt SF 2019.

Haurwitz studied under Caribou Biosciences’ co-founder Jennifer Doudna — one of the scientists who discovered CRISPR’s gene editing applications — and Caribou was formed to be the conduit through which the groundbreaking research from the Berkeley lab would become products that companies could use.

Short for “Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats”, CRISPR works by targeting certain sequences of DNA — the genetic instructions for the development and reproduction of all organisms — and then binding them to an enzyme that cuts the specific sequence.

Once edited, researchers can add or simply delete pieces of genetic material, or change the DNA by replacing a segment with customized code designed to achieve specific functions.

There are few industries that CRISPR doesn’t have the power to transform. Already, Caribou Biosciences technology is being used at Intellia, which is developing therapies based on CRISPR technologies (Haurwitz is a co-founder). And that’s just the beginning.

Caribou’s chief executive thinks of her company as a platform for developing technologies in therapeutics, research, agriculture and industrial biology.

Already, CRISPR technologies are being used to biologically manufacture chemicals, replace pesticides and fertilizers, and provide cures for rare diseases once though impossible.

“Any market with bio-based products will be changed by gene editing,” Haurwitz has said.

At SF Disrupt Haurwitz will talk about the implications of that transformation, and what’s ahead for the company that’s leading the charge in this genetic revolution.

Tickets are available here.

Powered by WPeMatico

Tray.io, the startup that wants to put automated workflows within reach of line of business users, announced a $37 million Series B investment today.

Spark Capital led the round with help from Meritech Capital, along with existing investors GGV Capital, True Ventures and Mosaic Ventures. Under the terms of the deal Spark’s Alex Clayton will be joining the Tray’s board of directors. The company has now raised over $59 million.

Rich Waldron, CEO at Tray, says the company looked around at the automation space and saw tools designed for engineers and IT pros and wanted to build something for less technical business users.

“We set about building a visual platform that would enable folks to essentially become programmers without needing to have an engineering background, and enabling them to be able to build out automation for their day-to-day role.”

He added, “As a result, we now have a service that can be used in departments across an organization, including IT, whereby they can build extremely powerful and flexible workflows that gather data from all these disparate sources, and carry out automation as per their desire.”

Alex Clayton from lead investor Spark Capital sees Tray filling in a big need in the automation space in a spot between high end tools like Mulesoft, which Salesforce bought last year for $6.5 billion, and simpler tools like Zapier. The problem, he says, is that there’s a huge shortage of time and resources to manage and really integrate all these different SaaS applications companies are using today to work together.

“So you really need something like Tray because the problem with the current Status Quo [particularly] in marketing sales operations, is that they don’t have the time or the resources to staff engineering for building integrations on disparate or bespoke applications or workflows,” he said.

Tray is a seven year old company, but started slowly taking the first 4 years to build out the product. They got $14 million Series A 12 months ago and have been taking off ever since. The company’s annual recurring revenue (ARR) is growing over 450 percent year over year with customers growing by 400 percent, according to data from the company. It already has over 200 customers including Lyft, Intercom, IBM and SAP.

The company’s R&D operation is in London, with headquarters in San Francisco. It currently has 85 employees, but expects to have 100 by the end of the quarter as it begins to put the investment to work.

Powered by WPeMatico

The antitrust argument that says big tech needs breaking up to stop platforms abusing competition and consumers in a two-faced role as seller and (manipulative) marketplace may only just be getting going on a mainstream political stage — but startups have been at the coal face of the fight against crushing platform power for years.

Presearch, a 2017-founded, pro-privacy blockchain-based startup that’s using cryptocurrency tokens as an incentive to decentralize search — and thereby (it hopes) loosen Google’s grip on what Internet users find and experience — was born out of the frustration, almost a decade before, of trying to build a local listing business only to have its efforts downranked by Google.

That business, Silicon Valley-based ShopCity.com, was founded in 2008 and offers local business search on Google’s home turf — operating sites like ShopPaloAlto.com and ShopMountainView.com — intended to promote local businesses by making them easier to find online.

But back in 2011 ShopCity complained publicly that Google’s search ranking systems were judging its content ‘low quality’ and relegating its listings pages to the unread deeps of search results. Listings which, nonetheless, had backing and buy in from city governments, business associations and local newspapers.

ShopCity went on to complain to the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC), arguing Google was unfairly favoring its own local search products.

Going public with its complaint brought it into contact with sceptical segments of the tech press more accustomed to cheerleading Google’s rise than questioning the agency of its algorithms.

“We have developed a very comprehensive and holistic platform for community commerce, and that is why companies like The Buffalo News, owned by Berkshire Hathaway, have partnered up with us and paid substantial licensing fees to use our system,” wrote ShopCity co-founder Colin Pape, responding to a dismissive Gigaom article in November 2011 by trying to engage the author in comments below the fold.

“The fact that Google recently began copying our multi-domain model… and our in-community approach, is a good indication that we are onto something and not just a ‘two-bit upstart’,” Pape went on. “Google has stated that the local space is of great importance to them… so they definitely have a motive to hinder others from becoming leaders, and if all it takes to stop a competitor from developing is a quick tweak to a domain profile, then why not?”

While the FTC went on to clear Google of anti-competitive behavior in the ShopCity case, Europe’s antitrust authorities have taken a very different view about Mountain View’s algorithmic influence: The EU fined Google $2.73BN in 2017 after a lengthy investigations into its search comparison service which found, in a scenario similar to ShopCity’s contention, Google had demoted rival product search services and promoted its own competing comparison search product.

That decision was the first of a trio of multibillion EU fines for Google: A record-breaking $5BN fine for Android antitrust violations fast-followed in 2018. Earlier this year Google was stung a further $1.7BN for anti-competitive behavior related to its search ad brokering business.

“Google has given its own comparison shopping service an illegal advantage by abusing its dominance in general Internet search,” competition commissioner Margrethe Vestager said briefing press on the 2017 antitrust decision. “It has harmed competition and consumers.”

Of course fines alone — even those that exceed a billion dollars — won’t change anything where tech giants are concerned. But each EU antitrust decision requires Google to change its regional business practices to end the anti-competitive conduct too.

Commission authorities continue monitoring Google’s compliance in all three cases, leaving the door open for further interventions if its remedies are deemed inadequate (as rivals continue to complain). So the search giant remains on close watch in Europe, where its monopoly in search puts special conditions on it not to break EU competition rules in any other markets it operates in or enters.

There are wider signs, too, that increasing antitrust scrutiny of big tech — including the idea of breaking platforms up that’s suddenly inflated into a mainstream political talking point in the U.S. — is lifting a little of the crushing weight off of Google competitors.

One example: Google quietly added privacy-focused search rival DuckDuckGo to the list of default search engines offered in its Chrome browser in around 60 markets earlier this year.

DDG is a veteran pro-privacy search engine Google rival that’s been growing usage steadily for years. Not that you’d have guessed that from looking at Chrome’s selective lists prior to the aforementioned silent update: From zero markets to ~60 overnight does look rather  .

.

Rising antitrust risk could help unlatch more previously battened down platform hatches in a way that’s helpful to even smaller Google rivals. Search startups like Presearch . (On the size front, it’s just passed a million registered users — and says monthly active users for its beta are ~250k. Early adopters skew power user + crypto geek.)

Google’s dominance in search remains a given for now but a fresh wind is rattling tech giants thanks to a shift in tone around technology and antitrust, fuelled by societal concern about wider platform power and impacts, that’s aligned with fresh academic thinking.

And now growing, cross-spectrum political appetite to regulate the Internet. Or, to put it another way, the tech backlash smells like a vote winner.

That may seem counterintuitive when platforms have built massive consumer businesses by heavily marketing ‘free’ consumer-friendly services. But their shiny freebies have sprouted a hydra of ugly heads in recent years — whether it’s Facebook-fuelled, democracy-denting disinformation; YouTube-accelerated hate speech and extremism; or Twitter’s penchant for creating safe spaces for nazis to make friends and influence people.

Add to that: Omnipresent creepy ads that stalk people around the Internet. And a fast-flowing river of data breach scandals that have kept a steady spotlight on how the industry systematically plays fast and loose with people’s data.

European privacy regulations have further helped decloak adtech via an updated privacy legal framework that highlights how very many faceless companies are lurking in the background of the Internet, making money by selling intelligence they’ve gleaned by spying on what web users are browsing.

And that’s just the consumer side. For small businesses and startups trying to compete with platform goliaths engineered and optimized to throw their bulk around, deploying massive networks and resources to tractor-beam and data mine anything — from product development; to usage and app trends; to their next startup acquisition — the feeling can be one of complete impotence. And, well, burning injustice.

“That was actually the real genesis moment behind [Presearch] — the realization of just how big Google is,” Pape tells TechCrunch, recounting the history of the ShopCity FTC complaint. “In 2011 we woke up one day and found out that 80-90% of our Google traffic had disappeared and all of these sites, some of which had been online for more than a decade and were being run in partnership with city governments and chambers of commerce, they were all basically demoted onto page eight of Google.

“Even if you typed them by name… Google had effectively, in their own backyard, shut down this local initiative.”

“We ended up participating in this [FTC] investigation and ultimately it cleared Google but we’ve been really aware of the market power that they have — and certainly what could be perceived as monopolistic practices,” he adds. “It’s a huge challenge. Anybody trying to do any sort of publishing or anything really on the web, Google is the gatekeeper.”

Now, with Presearch, Pape and co are hoping to go after Google in its techie backyard — of search.

Breaking the “Google habit” and opening up web users to a richer and more diverse field of search alternatives is the name of the game.

Presearch’s vision is a community-owned, choice-rich online playing field in the place where the Google search box normally squats; a sort of pluralist, collaborative commons that welcomes multiple search providers and rewards and surfaces community-curated search results to further diversity — encouraging Internet users to discover a democratized multiplicity of search results, not just the things big tech wants them to see.

Or as Pape puts it: “The ultimate vision is a fully decentralized search engine where the users are actually crawling the web as they surf — and where there’s kind of a framework for all of the participants within the ecosystem to be rewarded.”

This means that Presearch, which is developing a community-contributed search engine in addition to the federated search tool platform, is competing with the third party search providers it offers access to.

But from its point of view it’s ‘the more the merrier’; Call it search choices for customizable courses.

“Or as we like to think of it, like a ‘Switzerland of search’,” says Pape, adding: “We do want to make sure it’s all about the user.”

Presearch’s startup advisor roster includes names that will be familiar to the wider blockchain community: Ethereum co-founder and founder of Decentral, Anthony Di Iorio; Rich Skrenta, founder and CEO of startup search engine Blekko (acquired by IBM Watson back in 2015); and industry lawyer, Addison Cameron-Huff.

“When you’re a producer on the web you realize how much control Google does really have over user traffic. Yet there are thousands of different search resources that are out there that are subsisting underneath of Google,” continues Pape. “So we’re really trying to give them more of a platform that a lot of these different providers — including DuckDuckGo, Qwant — could get behind to basically break that Google dependency and make it easier for them to have a direct relationship with the their audience.”

Of course they’re nowhere near challenging Google’s grip yet.

And like so many startups Presearch may never make good on the massive disruptive vision. It’s certainly got its work cut out. Being a startup in the Google-dominated search space makes the standard hostile success odds exponentially harsher.

“Presearch is a highly-ambitious project,” the startup admits in its WhitePaper. “Google is one of the best companies in the world, and #1 on the Internet. Improving on their results, experience, and integrations will be no small feat — many even say it’s impossible. However, we believe that collectively the community can creatively and elegantly fulfill its own search needs from the ground up and create an amazing and open search engine that is aligned with the interests of humanity, not just one company.”

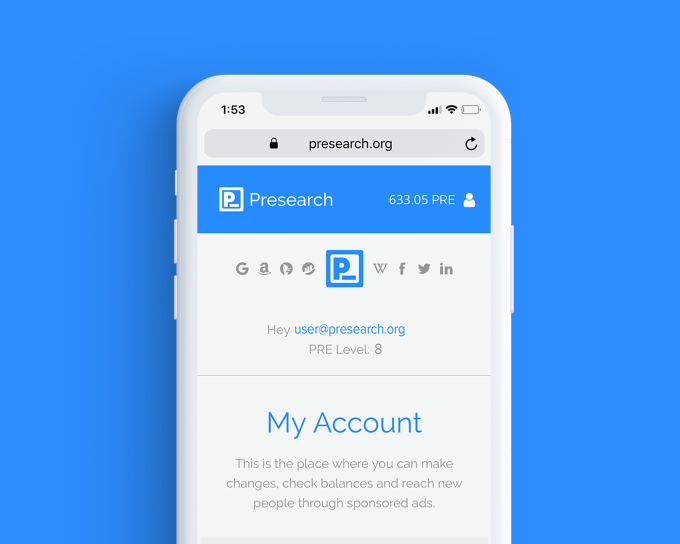

For now the beta product is, by Pape’s ready admission, more of a “search utility” — offering a familiar search box where users can type their queries but atop a row of icons that allow them to quickly switch between different search engines or services.

As well as offering Google search (the default search engine for now), DuckDuckGo is in the list, as is French search engine Qwant. Social platforms like Facebook and LinkedIn are also there to cater to people-focused queries. As is stuff like Wikipedia for community-edited authority. In all Pape says the beta offers access to around 80 search services.

The basic idea for now is to let users select the most appropriate search tool for whatever bit of info they’re trying to locate. Aka that “level playing field for a whole bunch of different search resources” idea.

This does look like a power tool with niche appeal — Pape says about a quarter of active users are actively switching between different engines; so ~75% are not — but which is being juiced, and here comes the crypto, by rewarding users for searching via the federated search field with a token called PRE.

Pape says users are provided with a quarter token per presearch performed — up to a cap of eight tokens per day. The current market value of the PRE token is around $0.05. (So the hardest working Presearchers could presumably call themselves ’40cents’.)

While there are ways for users to extract PRE from the platform if they wish, converting it to another cryptocurrency via community built exchanges, Pape says the intent is to create more of “a closed loop ecosystem”. Hence he says they’re busy building a portal for users to be able to sell PRE tokens to advertisers.

“We will be promoting this closed loop ecosystem but it is an open standardized currency,” he notes. “It is tradable on various exchanges that community members have set up so there is the ability for people to convert the Presearch token to bitcoin which can then be converted to any local currency.”

“We see as well as opportunity to really build out an ecosystem of places for people to spend the token as well,” he adds. “So that they can exchange it directly for either digital goods or material goods through an online platform. So that’s also in the works.”

As things stand Pape says most early adopters are ‘hodlers’. Which is to say they’re holding onto their PRE — speculating on as yet unknown token economics. (As it so often goes in the blockchain space — until, well, it suddenly doesn’t.)

“There is, as throughout the entire cryptocurrency space, an element of speculation,” he agrees. “People do tend to let their imaginations run wild so there’s kind of this interesting confluence of that core base utility — where you basically have a token that is backed by advertising, something that you can really convert it to. And then there is this potential concept of the value of the network, and of having essentially some time of stake in the value of that network.

“So there’s going to be this interesting period over the next couple of years as the token economics change as we go from this nascent startup mode into more of a full on operating mode. Where the value will likely change.”

For advertisers the PRE token buys targeted ad impressions placed in front of Presearch users by being linked to keywords used by searchers (or “targeted, non-intrusive, keyword sponsorships” as the website explainer puts it).

This is the virtuous, privacy-respecting circle Presearch is hoping to create.

Pape makes a point of emphasizing there is “no tracking” of users’ searches. Which means there’s no profiling of Preseachers by Presearch itself — ads are being targeted contextually, per the current keyword search.

But of course if you’re clicking through to a third party like Google or Facebook that’s a whole other matter; and the standard tracking caveats apply.

Presearch’s claim not to be storing or otherwise tracking users’ searches has to be taken on trust for now. However it intends to fully open source the platform to ensure truly accountable transparency in the near future. (Pape says they’re hoping they’ll be able to do so in a year.)

In the meantime he notes that the founders make themselves available to users via a messaging group on Telegram — contrasting that accessibility with the perfect unreachability of Google’s founders to the average (or really almost any) Google user.

In the modern age of messaging apps, and with their ecosystem’s community-building imperatives, these founders are most certainly not operating in a vacuum.

Currently one PRE token buys an advertiser four ad impressions on the platform — which is one lever Presearch will be able to pull on to influence the value of the token as the ecosystem develops.

“Ultimately [impressions per token] could go to ten, a hundred,” suggests Pape. “That’s obviously going to change the token — and we’ll basically do that as we see the market forces at work and how many people are actually willing to sell their tokens.

“We’ve currently got a pretty strong demand side equation right now. It’s like three to one demand to supply. A lot of the people that are earning tokens are not choosing to redeem them; they’re choosing to keep them in a wallet and hold onto them for the future. So it’s an interesting experiment in tokenomics.”

“It’s super volatile, there’s so much sentiment that’s involved, that’s really the core driver of the value,” he adds. “There’s no real fundamentals yet. Nobody has established any correlation between anything.”

Presearch began life as an internal search tool built for use at the founders’ other company to reduce time tracking down information online. And then the crypto boom caught their eye — and they saw an possible incentive structure to encourage Google users to switch.

“We didn’t really see a go to market strategy with it — search is a very challenging industry. But then when we really started looking at the cryptocurrency opportunity and the ability to potentially denominate an advertising platform in a token that could be utilized to incentivize people to switch we started thinking that it was viable; we put it out to the community, we got really good feedback on the need and on the messaging.”

A token sale followed, between July and November 2017, to raise funds for developing the platform — the obvious route for Presearch to grow a blockchain-based, community-sustaining, closed-loop ecosystem.

“One of the keys was really the ownership structure and making sure that all the participants within the ecosystem are aligned under one unit of account — which is the token. Vs having conflicting interests where there’s an equity incentive as well that may run counter to that token,” notes Pape.

The token sale raised an initial $7M but lucky timing meant Presearch was riding the cryptocurrency rollercoaster during an upward wave which meant funds appreciated to around $21M by the end of the sale period.

The first version of the platform was also launched in November of 2017, with the token itself launching at the end of the month.

Since then Pape says several hundred advertisers have participated in testing phases of the platform. A new version of the platform is pending for launch “shortly” — with a different ad unit which will arrive with a dozen “curated sponsors” on board. “There’s more brand exposure so we really want to be selective in the early days and making sure that we’re only partnering with aligned projects,” he adds.

Almost a year and a half on from the original platform launch Presearch has just made good on the number one community ask: Browser extensions to make the platform easier to use for search.

User surveys showed the biggest reason people dropped out was ease of use, according to Pape.

The new extension is available for Chrome, Brave and Firefox browsers, and works to shave off usability friction. Previously beta users had to set Presearch as their homepage or remember to type its address into the URL bar before searching.

“There’s a really good alignment of the core community but ultimately it does come down to changing user habit and behavior and that is always challenging,” he adds. “This new browser extension enables them to use the browser URL field or the search field and basically access Presearch through the UI that they’re used to and that they’ve been demanding.

Around a quarter of sign-ups stick around and become active users, according to Pape — who dubs that “already really high”. The team is expecting the new browser extensions to fuel “significant” further growth.

“We are getting ready to push it out to the users through email — [and anticipate] that we’re going to see a significant increase in the percentage of users utilizing it. And if that assumption holds through and everything really holds out we’re going to do a much more active push to grow the user base.”

They also launched an iOS Presearch app last year which taps into the voice search trend. Users can speak to search specific services with a library of sites that can be added to the app to enable deep searching of web resources, as well as apps running locally on the device. (So, for example, you could tap and tell it to ‘presearch Google Maps for London’ or ‘Spotify for Taylor Swift’.)

Competition concerns attached to the convenience of voice search — which risks further flattening consumer choice and concentrating already highly concentrated market power given its focus on filtering options to return just one search result — is an area of interest for antitrust regulators.

Europe’s antitrust chief Vestager said in an interview earlier this year that she was trying to figure out “how to have competition when you have voice search”. So perhaps Presearch’s federated platform approach offers a glimpse of a possible solution.

Pape sums up the overall competitive positioning that Presearch is shooting for as “Google for usage, DuckDuckGo for positioning”.

“We have been focused on the cryptocurrency community but there’s a really big opportunity to help all these other content providers, internet service providers,” he argues. “There’s all this traffic that is happening and it’s currently defaulting over to Google with really no compensation to the publishers — or to the tech provider. And so we’re going to be going after those opportunities pretty aggressively to get people to basically replace Google as the default that they use if they’re linking in an article to some more information or if they are an ISP and they have an error page that shows up if somebody types in a URL wrong or types in a strange query or something. Rather than have it go to Google, have it go to Presearch.”

Trying to make crypto more accessible is another focus. So there’s a built-in wallet to store PRE tokens — meaning users don’t have to have their own wallet set up to start earning crypto. (Though of course they can move PRE into a different wallet if/when they want.)

“As far as geographies go it’s a global audience but there’s a pretty heavy contingent of users in Central and South America… Mexico, Brazil, Venezuela,” he adds, discussing where early interest has been coming from. “There’s a lot of crypto adoption that’s happening down there due to this [combination] where they’re super tech savvy, they’ve got really great infrastructure, but they are still in a developing nation. So any of these types of crypto opportunities are very significant to them.”

While Google remains the staple default search option Presearch does offer its own search engine — leaning on third party APIs for search results.

Pape says the plan is to switch from Google to this engine as the default down the line. Albeit they can’t justify the switch yet.

“We want to provide users with the best search results to start,” he concedes, before adding: “Up until just recently Google’s results were certainly superior; now we think we’ve got something that is actually quite competitive.”

He couches the Presearch engine as “very similar to DuckDuckGo” but with a couple of “unique features” — including an infinite scroll view, rather than having search results paginated. (“As you’re scrolling it will automatically refresh the results.”)

“But the biggest thing really is that we have these open source community packages so anybody can submit to us a package that would get triggered by certain keywords and basically show up with results at the top of the search.”

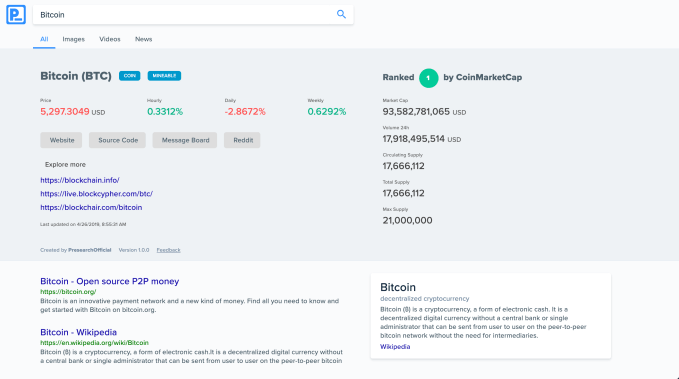

An example of one of these community packages can be seen by conducting a Presearch for “bitcoin” — which returns the below block of curated info related to the cryptocurrency above the rest of the search results:

Another example is currency conversions. When a currency conversion is typed into Presearch as a search query in the correct format (using relevant acronyms like USD and CAD) the query will surface a currency converter built by community members.

“It’s basically enabling anybody who knows HTML or Javascript to participate within the search ecosystem and add value to Presearch,” adds Pape.

The ultimate goal with the Presearch engine is to offer fully community-powered search where users not only create content packages and build out wider utility that can be served for particular keywords/searches but also curate these packages too.

The aim is also to have the community manage the entire process — such as by voting on what package should be the default where there are conflicting packages; and/or voting to approve package updates — much like Wikipedia editors work together on editing the online encyclopedia’s entries.

Pape notes that users would still be able to customize their own search results, such as by browsing the full suite of approved packages and selecting those that best meet their needs.

“The whole concept of the search engine is really more about user choice and giving them the ability to actively personalize their search results, and choose which contributors within the ecosystem they want to support,” he adds.

Of course Presearch is a very long way off that grand vision of wholly-community-powered search. So for now community packages are being curated by its core dev team.

Nor is it the first startup to dream big of community-powered and owned search. Not by a long, long chalk. It’s an idea that’s been kicked around the block many times before, even as Google’s dominating grip on search has cemented itself into place.

The level of crowdsourced effort required to generate differentiating value in the Google-dominated search space has proved a stumbling block for similarly minded startups wanting to compete head to head with Mountain View. And, clearly, Presearch will need a much larger user base if it’s to build and sustain enough community contributions to make its engine a compellingly useful product vs the usual search giant suspects.

But, as with Wikipedia, the idea is to keep building utility and momentum in growing increments. With — in its case — crypto rewards, backed by $21M in initial token sales, as the carrot to encourage community participation and contribution. So the founder logic sums to: ‘If we build it and pay people they’ll come’.

It’s worth noting that despite the community-focused mission Presearch’s current corporate structure is a Canadian corporation.

It does have a plan to transition to a foundation in future — with Pape envisaging distributing ~90%+ of the revenue that flows through the ecosystem to the various constituents and participants (searchers; node operators; curators; subject matter experts contributing to information indexes etc, etc), and retaining around 10% to fund operating the platform entity itself.

This is a structure familiar to many blockchain projects. Though Presearch is perhaps a bit unusual by being initially incorporated as a business.

“A lot of the crypto projects have done this foundation route [right off the bat] but really it’s more about taxes and it’s more about jurisdictional arbitrage and trying to minimize the potential regulatory risk,” Pape suggests. “For us, because of the way that we launched it, and our legal advisor [Cameron-Huff] — the founding lawyer for Ethereum — he gave us some really good guidance right out of the gate. And we’ve treated it as a business.

“We think we’ve got a really strong legal position and so we really didn’t need to do the offshore stuff at first. We figured we would get the usage and build up the core token economics. And then switch to an actual truly community-governed foundation, rather than a foundation in name which is governed by all the insiders — which is really what most of the crypto projects currently have done.”

For now Pape remains the sole shareholder of Presearch. Transitioning that sole ownership into the future foundation structure is likely a year out by his reckoning.

“One of the key concepts behind the project is ultimately providing an open source, transparent resource that is treated like more of a utility, that the community can provide input on and manage,” he adds. “So we’re looking at all the different government options.

“There’s a lot of technology being developed within the blockchain space right now. And some best practices that are starting to emerge. So we figured that we would give it a little while for that technology and those practices to mature and then we would be able to do that transition.”

Powered by WPeMatico

The San Francisco Bay Area is a global powerhouse at launching startups that go on to dominate their industries. For locals, this has long been a blessing and a curse.

On the bright side, the tech startup machine produces well-paid tech jobs and dollars flowing into local economies. On the flip side, it also exacerbates housing scarcity and sky-high living costs.

These issues were top-of-mind long before the unicorn boom: After all, tech giants from Intel to Google to Facebook have been scaling up in Northern California for over four decades. Lately however, the question of how many tech giants the region can sustainably support is getting fresh attention, as Pinterest, Uber and other super-valuable local companies embark on the IPO path.

The worries of techie oversaturation led us at Crunchbase News to take a look at the question: To what extent do tech companies launched and based in the Bay Area continue to grow here? And what portion of employees work elsewhere?

For those agonizing about the inflationary impact of the local unicorn boom, the data offers a bit of reassurance. While companies founded in the Bay Area rarely move their headquarters, their workforces tend to become much more geographically dispersed as they grow.

Just because a company is based in Northern California doesn’t mean most workers are there also. Headquarters, our survey shows, does not always translate into headcount.

“Headquarters location can often be the wrong benchmark to use to identify where employees are located,” said Steve Cadigan, founder of Cadigan Talent Ventures, a Silicon Valley-based talent consultancy. That’s particularly the case for large tech companies.

Among the largest technology employers in Northern California, Crunchbase News found most have fewer than 25 percent of their full-time employees working in the city where they’re headquartered. We lay out the details for 10 of the most valuable regional tech companies in the chart below.

With the exception of Intel, all of these companies have a double-digit percentage of employees at headquarters, so it’s not as if they’re leaving town. However, if you’re a new hire at Silicon Valley’s most valuable companies, it appears chances are greater that you’ll be based outside of headquarters.

Tesla, meanwhile, is somewhat of a unique case. The company is based in Palo Alto, but doesn’t crack the city’s list of top 10 employers. In nearby Fremont, Calif., however, Tesla is the largest city employer, with roughly 10,000 reportedly working at its auto plant there.(Tesla has about 49,000 employees globally.)

High-valuation private and recently public tech companies can also be pretty dispersed.

Although they tend to have a larger percentage of employees at headquarters than more-established technology giants, the unicorn crowd does like to spread its wings.

Take Uber, the poster child for this trend. Although based in San Francisco, the ride-hailing giant has fewer than one-fourth of its employees there. Out of a global workforce of around 22,300, only about 5,000 are SF-based.

It’s unclear if that kind of breakdown is typical. We had trouble assembling similar geographic employee counts at other Bay Area unicorns, mainly because cities break out numbers only for their 10 largest employers. The lion’s share of regional unicorns are San Francisco-based, and of them only Uber made the Top 10.

That said, there is another, rougher methodology for assessing who works at headquarters: job postings. At a number of the most valuable Bay Area-based unicorns — including Airbnb, Juul, Lime, Instacart, Stripe and the now-public Lyft — a high number of open positions are far from the home office. And as we wrote last year, private companies have been actively seeking out cities to set up secondary hubs.

Even for earlier-stage startups, it’s not uncommon to set up headquarters in the San Francisco area for access to financing and networking, while doing the bulk of hiring in another location, Cadigan said. The evolution of collaborative work tools has also enabled more companies to add staff working remotely or in secondary offices.

Plus, of course, unicorn startups tend to be national or global in focus, and that necessitates hiring where their customers are located.

As we wrap up, it’s worth bringing up how unusual it once was for denizens of a metro area to oppose a big influx of high-skill jobs. In the past couple of years, however, these attitudes have become more common. Witness Queens residents’ mixed reactions to Amazon’s HQ2 plans. And in San Francisco, a potential surge of newly minted IPO millionaires is causing some consternation among locals, along with jubilation among the realtor crowd.

Just as college towns retain room for new students by graduating older ones, however, it seems reasonable that sustaining Northern California’s strength as a startup hub requires locating jobs out-of-area as companies scale. That could be good news for other cities, including Austin, Phoenix, Nashville, Portland and others, which have emerged as popular secondary locations for fast-growing unicorns.

That said, we’re not predicting near-term contraction in Bay Area tech employment, particularly of the startup variety. The region’s massive entrepreneurial and venture ecosystem keeps on producing valuable newcomers well-capitalized to keep hiring.

Methodology

We looked only at employment at company headquarters (except for Apple) . Companies on the list may have additional employees based in other Northern California cities. For Apple, we included all Silicon Valley employees, per estimates by the Silicon Valley Business Journal.

Numbers are rounded to the nearest hundred for the largest employers. Most of the data is for full-time employees only. Large tech employers hire predominantly full-time for staff positions, so part-time, whether included or not, is expected to reflect only a very small percentage of employment.

Cities list their 10 largest employers in annual reports. We used either the annual reports themselves or data excerpted in Wikipedia, using calendar year 2017 or 2018.

Powered by WPeMatico

TechCrunch’s Connie Loizos published some interesting stats on seed and Series A financings this week, courtesy of data collected by Wing Venture Capital. In short, seed is the new Series A and Series A is the new Series B. Sure, we’ve been saying that for a while, but Wing has some clean data to back up those claims.

Years ago, a Series A round was roughly $5 million and a startup at that stage wasn’t expected to be generating revenue just yet, something typically expected upon raising a Series B. Now, those rounds have swelled to $15 million, according to deal data from the top 21 VC firms. And VCs are expecting the startups to be making money off their customers.

“Again, for the old gangsters of the industry, that’s a big shift from 2010, when just 15 percent of seed-stage companies that raised Series A rounds were already making some money,” Connie writes.

As for seed, in 2018, the average startup raised a total of $5.6 million prior to raising a Series A, up from $1.3 million in 2010.

Now on to IPO updates, then a closer look at all the companies raising big rounds. Want more TechCrunch newsletters? Sign up here. Contact me at kate.clark@techcrunch.com or @KateClarkTweets.

![]()

Slack: The workplace communication software provider dropped its S-1 on Friday ahead of a direct listing. That’s when companies sell existing shares directly to the market, allowing them to skip the roadshow and minimize the astronomical fees typically associated with an initial public offering. Here’s the TLDR on financials: Slack reported revenues of $400.6 million in the fiscal year ending January 31, 2019, on losses of $138.9 million. That’s compared to a loss of $140.1 million on revenue of $220.5 million for the year before. Slack’s losses are shrinking (slowly), while its revenues expand (quickly). It’s not profitable yet, but is that surprising?

Zoom was the Slack we thought Slack was all along.

— alex (PVD) (@alex) April 26, 2019

Uber: The ride-hail giant is fast approaching its IPO, expected as soon as next week. On Friday, the company established an IPO price range of $44 to $50 per share to raise between $7.9 billion and $9 billion at a valuation of approximately $84 billion, significantly lower than the $100 billion previously reported estimations. The most likely outcome is Uber will price above range and all the latest estimates will be way off course. Best to sit back and see how Uber plays it. Oh, and PayPal said it would make a $500 million investment in the company in a private placement, as part of an extension of the partnership between the two.

There are a lot of fascinating companies raising colossal rounds, so I thought I’d dive a bit deeper than I normally do. Bear with me.

Carbon: The poster child for 3D printing has authorized the sale of $300 million in Series E shares, according to a Delaware stock filing uncovered by PitchBook. If Carbon raises the full amount, it could reach a valuation of $2.5 billion. Using its proprietary Digital Light Synthesis technology, the business has brought 3D-printing technology to manufacturing, building high-tech sports equipment, a line of custom sneakers for Adidas and more. It was valued at $1.7 billion by venture capitalists with a $200 million Series D in 2018.

Canoo: The electric vehicle startup formerly known as Evelozcity is on the hunt for $200 million in new capital. Backed by a clutch of private individuals and family offices from China, Germany and Taiwan, the company is hoping to line up the new capital from some more recognizable names as it finalizes supply deals with vendors, according to reporting from TechCrunch’s Jonathan Shieber. The company intends to make its vehicles available through a subscription-based model and currently has 400 employees. Canoo was founded in 2017 after Stefan Krause, a former executive at BMW and Deutsche Bank, and another former BMW executive, Ulrich Kranz, exited Faraday Future amid that company’s struggles.

Starry: The Boston-based wireless broadband internet startup has authorized the sale of Series D shares worth up to $125 million, according to a Delaware stock filing. If Starry closes the full authorized raise it will hold a post-money valuation of $870 million. A spokesperson for the company confirmed it had already raised new capital, but disputed the numbers. The company has already raised more than $160 million from investors, including FirstMark Capital and IAC. The company most recently closed a $100 million Series C this past July.

Selina & Sonder: The Airbnb competitor Sonder is in the process of closing a financing worth roughly $200 million at a $1 billion valuation, reports The Wall Street Journal. Investors including Greylock Partners, Spark Capital and Structure Capital are likely to participate. Sonder is four years old but didn’t emerge from stealth until 2018. The startup, which turns homes into hotels, quickly attracted more than $100 million in venture funding. Meanwhile, another hospitality business called Selina has raised $100 million at an $850 million valuation. The company, backed by Access Industries, Grupo Wiese and Colony Latam Partners, builds living/co-working/activity spaces across the world for digital nomads.

Fresh funds: Mary Meeker has made history with the close of her new fund, Bond Capital, the largest VC fund founded and led by a female investor to date. Bond has $1.25 billion in committed capital. If you remember, Meeker ditched Kleiner Perkins last fall and brought the firm’s entire growth team with her. Kleiner said it was a peaceful split that would allow the firm to focus more on its early-stage efforts, leaving the growth investing to Bond. Fortune, however, reported this week that a power struggle of sorts between Meeker and Mamoon Hamid, who joined recently to reenergize the early-stage side of things, was a larger cause of her exit.

Plus, SOSV, a multi-stage venture firm that was founded as the personal investment vehicle of entrepreneur Sean O’Sullivan after his company went public in 1994, has raised $218 million for its third fund. The vehicle has a $250 million target that SOSV expects to meet. Already, the fund is substantially larger than the firm’s previous vehicle, which closed with $150 million.

A grocery delivery startup crumbles: Honestbee, the online grocery delivery service in Asia, is nearly out of money and trying to offload its business. Despite looking impressive from the outside, the company is currently in crisis mode due to a cash crunch — there’s a lot happening right now. TechCrunch’s Jon Russell dives in deep here.

Extra Crunch: “When it comes to working with journalists, so many people are, frankly, idiots. I have seen reporters yank stories because founders are assholes, play unfairly, or have PR firms that use ridiculous pressure tactics when they have already committed to a story.” Sign up for Extra Crunch for a full list of PR don’ts. Here are some other EC pieces to hit the wire this week:

Equity: If you enjoy this newsletter, be sure to check out TechCrunch’s venture-focused podcast, Equity. In this week’s episode, available here, Crunchbase News editor-in-chief Alex Wilhelm and I chat about Kleiner Perkins, Chinese IPOs and Slack & Uber’s upcoming exits.

Powered by WPeMatico

Hello and welcome back to Equity, TechCrunch’s venture capital-focused podcast, where we unpack the numbers behind the headlines.

Kate and Alex are back (again), bringing you the latest on the IPO front. As Friday is coming to a close, we’ll keep this post short to leave plenty of room for you to dig into the audio. Welcome to the weekend.

Up first we dug into Uber’s latest S-1 filing. This time, the company set a price range for itself (TechCrunch’s coverage here), valuing itself at $84 billion and also detailing estimates of its first-quarter results (Crunchbase News’s notes here).

We suspect Uber will ultimately price a top that range. Time will tell.

And then we turned to Slack, who’s direct listing will help set the historical tone for the unicorn era; screw your money, Slack says, we have our own. Well maybe not, but the company has impressive growth, killer margins, and, to our surprise, larger GAAP deficits than we expected. The company’s filing was fascinating.

But worry not, we can figure out how to value Slack. It’s Uber that left us scratching our heads. Expect next week to be another blizzard of news and numbers.

Thanks as always for listening to the show. We’ve never had more downloads than these last few weeks. It means a lot that you want to hang out with us. Don’t forget that we have an email address (equitypod@techcrunch.com), and a hashtag that Alex needs to learn to use: #equitypod.

Equity drops every Friday at 6:00 am PT, so subscribe to us on Apple Podcasts, Overcast, Pocket Casts, Downcast and all the casts.

Powered by WPeMatico

Earlier today, agents from the FBI searched the offices of uBiome, the medical testing company that sells analyses of an individual’s microbiome — the bacteria that live in the gut, according to a report in The Wall Street Journal.

The FBI is reportedly investigating uBiome’s billing practices, the WSJ reported.

“I can confirm that special agents from the FBI San Francisco Division are present at 360 Langton Street in San Francisco conducting court-authorized law enforcement activity. Due to the ongoing nature of the investigation, I cannot provide any additional details at this time,” a spokesperson for the FBI confirmed.

360 Langton street is listed as an address for uBiome.

Numerous questions surrounding the clinical validity and efficacy of microbiome analysis remain, and uBiome could be under the microscope for the fact that it offers physician-ordered and consumer-requested test kits.

“We are cooperating fully with federal authorities on this matter. We look forward to continuing to serve the needs of healthcare providers and patients,” a spokesperson for the company wrote in an email to TechCrunch.

The company is one of a growing number of startups raising money for consumer-facing and clinical applications around the nascent field of microbiome research.

Founded by Jessica Richman in 2012, uBiome has gone from a crowdfunded startup that raised $350,000 to begin developing testing for microbiome health to a company that reportedly raised $83 million last year.

As uBiome faces potential legal troubles with the federal government, other microbiome startups are also struggling.

Earlier this week, Arivale, a company that used a combination of genetic and microbiome testing and coaching to improve long-term consumer health, was forced to shut down its “consumer program” after raising more than $50 million from investors, including Maveron, Polaris Partners and ARCH Venture Partners.

“Regrettably… we are terminating our consumer program. Our decision to do so is attributable to the simple fact that the cost of providing the service exceeds what our customers can pay for it,” the company wrote on its website. “We believe the costs of collecting the genetic, blood and microbiome assays that form the foundation of the program will eventually decline to a point where the program can be delivered to consumers cost-effectively. However, we are unable to continue to operate at a loss until that time arrives.”

Some customers of uBiome were able to avoid those costs by having insurance providers pick up the tab. What the government is likely investigating is whether those insurance claims were fraudulent.

Powered by WPeMatico

Whenever a security startup lands on my desk, I have one question: Who’s the chief security officer (CSO) and when can I get time with them?

Having a chief security officer is as relevant today as a chief marketing officer (CMO) or chief revenue boss. Just as you need to make sure your offering looks good and the money keeps rolling in, you need to show what your security posture looks like.

Even for non-security startups, having someone at the helm is just as important — not least given the constant security threats that all companies face today, they will become a necessary part of interacting with the media. Regardless of whether your company builds gadgets or processes massive amounts of customer data, security has to be at the front of mind. It’s no good simply saying that you “take your privacy and security seriously.” You have to demonstrate it.

A CSO has several roles and they will wear many hats. Depending on the kind of company you have, they will work to bolster your company’s internal processes and policies on keeping not only your corporate data safe but also the data of your customers. They also will be consulted on security practices of your app or product or service to make sure you’re complying with consumer-expected privacy expectations — and not the overbearing and all-embracing industry standards of vacuuming up as much data as there is.

But for the average security startup, a CSO should also act as the point-person for all technical matters associated with their company’s product or service. A CSO can be an evangelist for the infosec professional who can speak to their company’s offering — and to reporters, like me.

In my view, no startup of any size — especially a security startup — should be without a CSO.

The reality is about 95 percent of the world’s wealthiest companies don’t have one. Facebook hasn’t had someone running the security shop since August. It may be a coincidence that the social networking giant has faced breach after exposure after leak after scandal, and it shows — the company is running around headless without a direction of where to go.

Powered by WPeMatico

Sam Altman’s little brother Jack is an entrepreneur, too.

Jack Altman, whose resume includes a stint as vice president of business development at Teespring, has raised $15 million in Series B funding for his startup, Lattice, a modern approach to corporate goal setting. Shasta Ventures led the round, with participation from Thrive Capital, Khosla Ventures and Y Combinator, the latter being the organization his brother led as president until very recently.

Lattice, used by high-growth companies like Reddit, Slack, Coinbase and Glossier, helps human resources professionals develop insights about their teams. Founded in 2015, Altman and Eric Koslow, like most entrepreneurs, developed the idea for Lattice out of their own pain points.

“We realized that with quarterly goal settings, OKRs, we would write them up and get the leadership together and then they would sit on a shelf and nothing would happen,” Altman told TechCrunch.

Lattice, a SaaS business, is a flexible platform that caters to startups and larger businesses’ specific cultures, management practices and varying approaches to employee engagement. The product, inspired by platforms like Gmail and Slack, is designed with consumers in mind. Lattice, the team hopes, has a look and feel that makes incumbent HR platforms feel antiquated.

The product makes it simple for employees and their managers to complete engagement surveys, share feedback, arrange one-on-one meetings and complete comprehensive performance reviews with a larger goal of reworking the company goal-setting process entirely. No more once-yearly check-ins; Lattice enables businesses to check-in with their employees on a weekly basis.

Lattice currently has 1,200 customers, 60 employees and was cash flow break-even for the first time in Q1 2019. With the latest financing, the San Francisco-based startup plans to invest in product development.

“Life is short,” Altman said. “You want to have work that you enjoy and an office that feels good to be at.”

Lattice has previously raised capital from investors including SV Angel, Marc Benioff, Slack Fund and Fuel Capital, Sam Altman, Elad Gil, Alexis Ohanian, Kevin Mahaffey, Daniel Gross and Jake Gibson. Lattice completed the Y Combinator startup accelerator in 2016.

Powered by WPeMatico