Startups

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Vacasa, a provider of vacation rental management services akin to Airbnb, has agreed to acquire Wyndham Vacation Rentals from Wyndham Destinations.

Portland-based Vacasa will pay Wyndham a total of $162 million, including at least $45 million in cash at closing and upwards of $30 million in Vacasa equity.

Vacasa, founded in 2009, has raised $207.5 million in venture capital funding to date from investors such as Assurant Growth Investing and NewSpring Capital.

Its acquisition of Wyndham Vacation Rentals will bring a number of brands, including ResortQuest, Kaiser Realty and Vacation Palm Springs, under its ownership and will expand its portfolio to include 9,000 new properties.

“We are excited to partner with the pioneering company in the short-term rental industry that helped make vacation homes popular for so many families around the world,” Vacasa founder and chief executive officer Eric Breon said in a statement. “Combining Wyndham Vacation Rentals’ decades of operational excellence with Vacasa’s next-generation technology will deliver the industry’s best vacation rental experiences.”

The deal comes amid a period of growth for the Oregon business, which says it expects to bring in more than $1 billion in gross bookings and roughly $500 million in net revenue in the next year.

The acquisition, announced this morning, is projected to close this fall.

Powered by WPeMatico

Just yesterday, we experienced yet another major breach when Capital One announced it had been hacked and years of credit card application information had been stolen. Another day, another hack, but the question is how can companies protect themselves in the face of an onslaught of attacks. Confluera, a Palo Alto startup, wants to help with a new tool that purports to stop these kinds of attacks in real time.

Today the company, which launched last year, announced a $9 million Series A investment led by Lightspeed Venture Partners . It also has the backing of several influential technology execs, including John W. Thompson, who is chairman of Microsoft and former CEO at Symantec; Frank Slootman, CEO at Snowflake and formerly CEO at ServiceNow; and Lane Bess, former CEO of Palo Alto Networks.

What has attracted this interest is the company’s approach to cybersecurity. “Confluera is a real-time cybersecurity company. We are delivering the industry’s first platform to deterministically stop cyberattacks in real time,” company co-founder and CEO Abhijit Ghosh told TechCrunch.

To do that, Ghosh says, his company’s solution watches across the customer’s infrastructure, finds issues and recommends ways to mitigate the attack. “We see the problem that there are too many solutions which have been used. What is required is a platform that has visibility across the infrastructure, and uses security information from multiple sources to make that determination of where the attacker currently is and how to mitigate that,” he explained.

Microsoft chairman John Thompson, who is also an investor, says this is more than just real-time detection or real-time remediation. “It’s not just the audit trail and telling them what to do. It’s more importantly blocking the attack in real time. And that’s the unique nature of this platform, that you’re able to use the insight that comes from the science of the data to really block the attacks in real time.”

It’s early days for Confluera, as it has 19 employees and three customers using the platform so far. For starters, it will be officially launching next week at Black Hat. After that, it has to continue building out the product and prove that it can work as described to stop the types of attacks we see on a regular basis.

Powered by WPeMatico

When Stackin’ initially pitched itself as part of the Techstars Los Angeles accelerator program two years ago, the company was a video platform for financial advice targeting a millennial audience too savvy for traditional advisory services.

Now, nearly two years later, the company has pivoted from video to text-based financial advice for its millennial audience and is offering a new spin on lead generation for digital banks.

The company has launched a new, no-fee, checking and savings account feature in partnership with Radius Bank, which offers users a 1% annual percentage yield on deposits.

And Stackin’ has raised $4 million in new cash from Experian Ventures, Dig Ventures and Cherry Tree Investments, along with supplemental commitments from new and previous investors including Social Leverage, Wavemaker Partners and Mucker Capital.

“Stackin’ has a unique and highly effective approach to connect and communicate with an entire generation of younger consumers around finance,” said Ty Taylor, group president of Global Consumer Services at Experian, in a statement.

Founded two years ago by Scott Grimes, the former founder of Uproxx Media, and Kyle Arbaugh, who served as a senior vice president at Uproxx, Stackin’ initially billed itself as the Uproxx of personal finance.

It turns out that consumers didn’t want another video platform.

“Stackin’ is fundamentally changing the shape and context of what a financial relationship means by creating a fun, inclusive and judgement free environment that empowers our users to learn and take action through messaging,” said Scott Grimes, CEO and co-founder of Stackin’, in a statement. “This funding allows us to build out new features around banking and investing that will enhance the relationship with our customers.”

Later this fall the company said it would launch a new investment feature that will encourage Stackin’ users to participate in the stock market. It’s likely that this feature will look something like the Acorns model, which encourages users to invest in diversified financial vehicles to get them acquainted with the stock market before enabling individual trades on stocks.

According to Grimes, the company made the switch from video to text in March 2018 and built a custom messaging platform on Twilio to service the company’s 500,000 users.

“In a short time, we have built a large customer base with a demographic that is typically hard to reach. Having financial institutions like Experian come on board as an investor is a testament that this model is working,” Grimes wrote in an email.

Powered by WPeMatico

Even before pitching onstage at Y Combinator, Indian car refueling startup MyPetrolPump has managed to snag $1.6 million in seed financing.

The business, which is similar to startups in the U.S. like Filld, Yoshi and Booster Fuels, took 10 months to design and receive approval for its proprietary refueling trucks that can withstand the unique stresses of providing logistics services in India.

Together with co-founder Nabin Roy, a serial startup entrepreneur, MyPetrolPump co-founder and chief executive Ashish Gupta pooled $150,000 to build the company’s first two refuelers and launch the business.

MyPetrolPump began operating out of Bangalore in 2017 working with a manufacturing partner to make the 20-30 refuelers that the company expects it will need to roll out its initial services. However, demand is far outstripping supply, according to Gupta.

“We would need hundreds of them to fulfill the demand,” Gupta says. In fact the company is already developing a licensing strategy that would see it franchise out the construction of the refueling vehicles and regional management of the business across multiple geographies.

Bootstrapped until this $1.6 million financing, MyPetrolPump already has five refueling vehicles in its fleet and counts 2,000 customers already on its ledger.

These are companies like Amazon and Zoomcar, which both have massive fleets of vehicles that need refueling. Already the company has delivered 5 million liters of fuel with drivers working daily 12-hour shifts, Gupta says.

While services like MyPetrolPump have cropped up in the U.S. as a matter of convenience, in the Indian context, the company’s offering is more of necessity, says Gupta.

“In the Indian context, there’s pilferage of fuel,” says Gupta. Bus drivers collude with gas station operators to skim money off the top of the order, charging for 50 liters of fuel but only getting 40 liters pumped in. Another problem that Gupta says is common is the adulteration of fuel with additives that can degrade the engine of a vehicle.

There’s also the environmental benefit of not having to go all over to refill a vehicle, saving fuel costs by filling up multiple vehicles with a single trip from a refueling vehicle out to a location with a fleet of existing vehicles.

The company estimates it can offset 1 million tons of carbon in a year — and provide more than 300 billion liters of fuel. The model has taken off in other geographies as well. There’s Toplivo v Bak in Russia (which was acquired by Yandex), Gaston in Paris and Indonesia’s everything mobility company, Gojek, whose offerings also include refueling services.

And Gupta is preparing for the future as well. If the world moves to electrification and electric vehicles, the entrepreneur says his company can handle that transition as well.

“We are delivering a last-mile fuel delivery system,” says Gupta. “If tomorrow hydrogen becomes the dominant fuel we will do that… If there is electricity we will do that. What we are building is the convenience of last-mile delivery to energy at the doorstep.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Money from big tech companies and top VC firms is flowing into the nascent “virtual beings” space. Mixing the opportunities presented by conversational AI, generative adversarial networks, photorealistic graphics, and creative development of fictional characters, “virtual beings” envisions a near-future where characters (with personalities) that look and/or sound exactly like humans are part of our day-to-day interactions.

Last week in San Francisco, entrepreneurs, researchers, and investors convened for the first Virtual Beings Summit, where organizer and Fable Studio CEO Edward Saatchi announced a grant program. Corporates like Amazon, Apple, Google, and Microsoft are pouring resources into conversational AI technology, chip-maker Nvidia and game engines Unreal and Unity are advancing real-time ray tracing for photorealistic graphics, and in my survey of media VCs one of the most common interests was “virtual influencers”.

The term “virtual beings” gets used as a catch-all categorization of activities that overlap here. There are really three separate fields getting conflated though:

These can overlap — there are humanoid virtual influencers for example — but they represent separate challenges, separate business opportunities, and separate societal concerns. Here’s a look at these fields, including examples from the Virtual Beings Summit, and how they collectively comprise this concept of virtual beings:

Virtual companions are conversational AI that build a unique 1-to-1 relationship with us, whether to provide friendship or utility. A virtual companion has personality, gauges the personality of the user, retains memory of prior conversations, and uses all that to converse with humans like a fellow human would. They seem to exist as their own being even if we rationally understand they are not.

Virtual companions can exist across 4 formats:

While pop culture depictions of this include Her and Ex Machina, nascent real-world examples are virtual friend bots like Hugging Face and Replika as well as voice assistants like Amazon’s Alexa and Apple’s Siri. The products currently on the market aren’t yet sophisticated conversationalists or adept at engaging with us as emotional creatures but they may not be far off from that.

Powered by WPeMatico

Los Angeles-based Ordermark, the online delivery management service for restaurants founded by the scion of the famous, family-owned Canter’s Deli, said it has raised $18 million in a new round of funding.

The round was led by Boulder-based Foundry Group. All of Ordermark’s previous investors came back to provide additional capital for the company’s new funding, including: TenOneTen Ventures, Vertical Venture Partners, Mucker Capital, Act One Ventures and Nosara Capital, which led the Series A funding.

“We created Ordermark to help my family’s restaurant adapt and thrive in the mobile delivery era, and then realized that as a company, we could help other restaurants experiencing the same challenges. We’ve been gratified to see positive results come in from our restaurant customers nationwide,” said Alex Canter, in a statement.

A fourth-generation restaurateur, Canter built the technology on the back of his family deli’s own needs. The company has integrated with point of sale systems, kitchen displays and accounting tools, and with last-mile delivery companies.

As the company expands, it’s looking to increase its sales among the virtual restaurants powered by cloud kitchens and delivery services like Uber Eats, Seamless/Grubhub and others, the company said in a statement.

Although the business isn’t profitable, Ordermark is now in more than 3,000 restaurants. The company has integrations with more than 50 ordering services.

Powered by WPeMatico

Launch vehicles and their enormous rocket engines tend to receive the lion’s share of attention when it comes to space-related propulsion, but launch only takes you to the edge of space — and space is a big place. Tesseract has engineered a new rocket for spacecraft that’s not only smaller and more efficient, but uses fuel that’s safer for us down here on the surface.

The field of rocket propulsion has been advancing constantly for decades, but once in space, there’s considerably less variation. Hydrazine is a simple and powerful nitrogen-hydrogen fuel that’s been in use since the ’50s, and engines using it (or similar “hypergolic” propellants) power many a spacecraft and satellite today.

There’s just one problem: Hydrazine is horribly toxic and corrosive. Handling it must be done in a special facility, using extreme caution and hazmat suits, and very close to launch time — you don’t want a poisonous explosive sitting around any longer than it has to. As launches and spacecraft multiply and costs drop, hydrazine handling remains a serious expense and danger.

Alternatives for in-space propulsion are being pursued, like Accion’s electrospray panels, Hall effect thrusters (on SpaceX’s Starlink satellites) and light sails — but ultimately, chemical propulsion is the only real option for many missions and craft. Unfortunately, research into alternative fuels that aren’t so toxic hasn’t produced much in the way of results — but Tesseract says the time has come.

“There was some initial research done at China Lake Naval Station in the ’90s,” said co-founder Erik Franks, but it fizzled out when funds were reallocated. “The timing also wasn’t right because the industry was still dominated by very conservative defense contractors who were content with the flight-proven toxic propellant technology.”

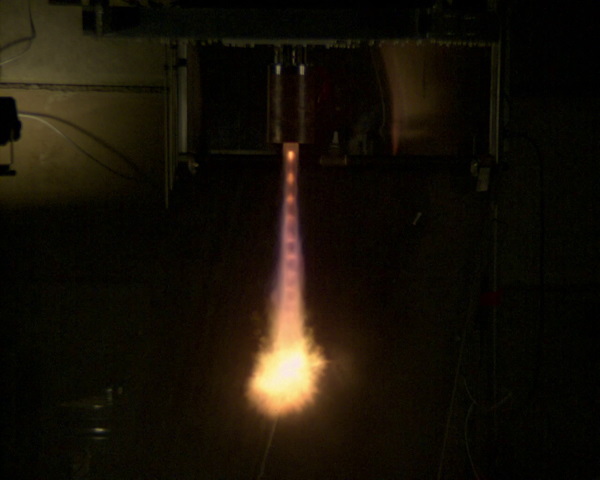

A live fire test of Tesseract’s Rigel engine.

The lapsed patents for these systems, however, pointed the team in the right direction. “The challenge for us has been going through the whole family of chemicals and finding which works for us. We’ve found a really good one — we’re keeping it as kind of a trade secret but it’s cheap, and really high-performance.”

You wouldn’t want to rinse your face with it, but you can fuel a spacecraft wearing Gore-Tex coveralls instead of a hermetically sealed hazmat suit. Accidental exposure doesn’t mean permanent tissue damage like it might with hydrazine.

The times have changed, as well. The trend in space right now is away from satellites that cost hundreds of millions and stay in geosynchronous orbit for decades, and toward smaller, cheaper birds intended to last only five or 10 years.

More spacecraft being made by more people makes safer, greener alternatives more attractive, of course: lower handling costs, less specialized facilities and so on further democratize the manufacturing and preparation processes. But there’s more to it than that.

If all anyone wanted was to eliminate hydrazine-based propulsion, they could replace the engine with an electric option like a Hall effect thruster, which gets its thrust from charged particles exiting the assembly and imparting an infinitesimal force in the opposite direction — countless times per second, of course. (It adds up.)

But these propulsion methods, while they have a high specific impulse — a measurement of how much force is generated per unit of fuel — they produce very little thrust. It’s like suggesting someone take a solar-powered car with a max speed of 5 MPH instead of a traditional car with a V6. You’ll get there, and economically, but not in a hurry.

Consider that a satellite, once brought to low orbit by a launch vehicle, must then ascend on its own power to the desired altitude, which may be hundreds of kilometers above. If you use a chemical engine, that could be done in hours or days, but with electric, it might take months. A military comsat meant to stay in place for 20 years can spare a few months at the outset, but what about the thousands of short-life satellites a company like Starlink plans to launch? If they could be operational a week after launch rather than months, that’s a non-trivial addition to their lifespan.

“If you can get rid of the toxicity and handling costs of conventional chemical propulsion, but maintain performance, we think green chemical is a clear winner for the new generation of satellites,” Franks said. And that’s what they claim to have created. Not just on paper either, obviously; here’s a video of a fire test from earlier this year.

“It’s also important at end of life, where doing a long, slow spiral deorbit, repeatedly crossing the orbits of other satellites, dramatically increases the risk of collision,” he continued. “For responsibly managing these large, planned constellations the ability to quickly deorbit at end of life will be especially important to avoid creating an unsustainable orbital debris problem.”

Tesseract has only seven full-time employees, and was a part of Y Combinator’s Summer 2017 class. Since (and before) then they’ve been hard at work engineering the systems they’ll be offering, and building relationships with aerospace.

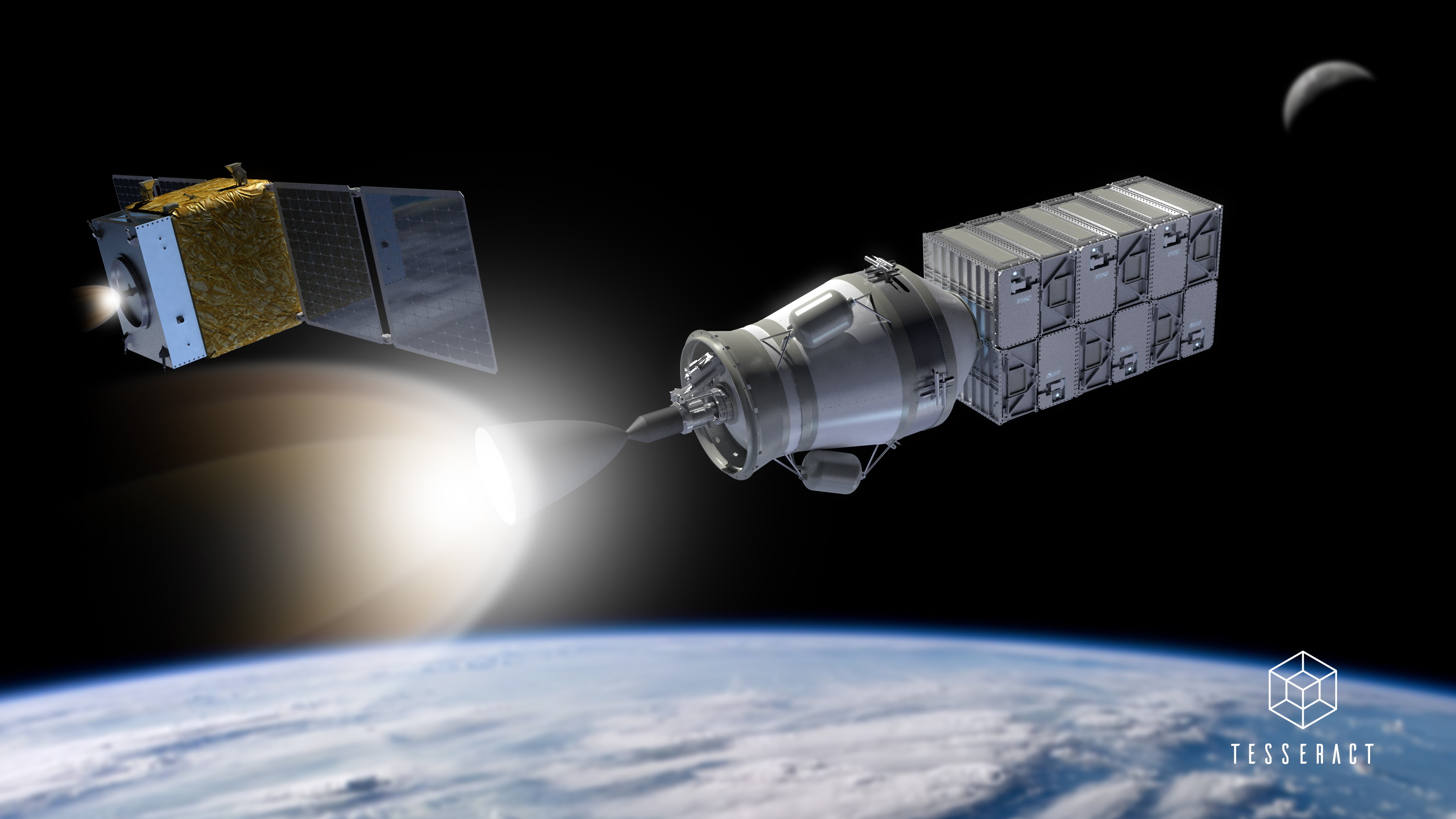

A render of Tesseract’s two flagship products — Adhara on the left and Polaris on the right.

They’ve raised a $2 million seed round, but you don’t have to be a rocket scientist to know that’s not the kind of money that puts things into space. Fortunately, the company already has its first customers, one of which is still in stealth but plans to launch a Moon mission next year (and you better believe we’re following up on that hot tip). The other is Space Systems/Loral, or SSL, which has signed a $100 million letter of intent.

There are two main products Tesseract plans to offer. Polaris is a “kickstage,” essentially a short-range spacecraft used to deliver satellites to more distant orbits after being taken up to space by a launch vehicle. It’s powered by the company’s larger Rigel engines; this is the platform purportedly headed to the Moon, and you can see it propelling a clutch of 6U smallsats on the right in the image above.

But Franks thinks the money is elsewhere. “The systems we think will be a bigger market opportunity are the smallsat propulsion systems,” he said. Hence the second product, Adhara, a propulsion bus for smaller satellites and craft that the company is focusing on keeping straightforward, compact and, of course, green. (It’s the smaller rig in the image above; the thrusters are named Lyla.)

“We’ve heard from customers that complete, turnkey systems are what they mostly want, rather than buying components from many vendors and doing all the systems integration themselves like the old-school satellite manufacturers have historically done,” Franks said. So that’s what Adhara is for: “Keep it simple, bolt it on there, let it maneuver where it needs to go.”

Engineering these engines was no cakewalk, naturally, but Tesseract wasn’t reinventing the wheel. The principles are very similar to traditional engines, so development costs weren’t ridiculous.

The company isn’t pretending these are the only solutions that make sense now. If you need to have the absolute lowest mass or volume dedicated to propulsion, or don’t really care if it takes a week or a year to get where you’re going, electric propulsion is still probably a better deal. And for major missions that require high delta-V and don’t mind dealing with the attendant dangers, hydrazine is still the way to go. But the market that’s growing the most is neither one of these, and Tesseract’s engines sit in a middle ground that’s efficient, compact and far less dangerous to work with.

Powered by WPeMatico

Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter have failed their task of monitoring and moderating the content that appears on their sites; what’s more, they failed to do so well before they knew it was a problem. But their incidental cultivation of fringe views is an opportunity to recast their role as the services they should be rather than the platforms they have tried so hard to become.

The struggles of these juggernauts should be a spur to innovation elsewhere: While the major platforms reap the bitter harvest of years of ignoring the issue, startups can pick up where they left off. There’s no better time to pass someone up as when they’re standing still.

At the heart of the content moderation issue is a simple cost imbalance that rewards aggression by bad actors while punishing the platforms themselves.

To begin with, there is the problem of defining bad actors in the first place. This is a cost that must be borne from the outset by the platform: With the exception of certain situations where they can punt (definitions of hate speech or groups for instance), they are responsible for setting the rules on their own turf.

That’s a reasonable enough expectation. But carrying it out is far from trivial; you can’t just say “here’s the line; don’t cross it or you’re out.” It is becoming increasingly clear that these platforms have put themselves in an uncomfortable lose-lose situation.

If they have simple rules, they spend all their time adjudicating borderline cases, exceptions, and misplaced outrage. If they have more granular ones, there is no upper limit on the complexity and they spend all their time defining it to fractal levels of detail.

Both solutions require constant attention and an enormous, highly-organized and informed moderation corps, working in every language and region. No company has shown any real intention to take this on — Facebook famously contracts the responsibility out to shabby operations that cut corners and produce mediocre results (at huge human and monetary cost); YouTube simply waits for disasters to happen and then quibbles unconvincingly.

Powered by WPeMatico

Dark has been keeping its startup in the dark for the last couple of years while it has built a unique kind of platform it calls “deployless” software development. If you build your application in Dark’s language inside of Dark’s editor, the reward is you can deploy it automatically on Dark’s infrastructure on Google Cloud Platform without worrying about all of the typical underlying deployment tasks.

The company emerged from stealth today and announced $3.5 million in seed funding, which it actually received back in 2017. The founders have spent the last couple of years building this rather complex platform.

Ellen Chisa, CEO and co-founder at the company, admits that the Dark approach requires learning to use her company’s toolset, but she says the trade-off is worth it because everything has been carefully designed to work in tandem.

“I think the biggest downside of Dark is definitely that you’re learning a new language, and using a different editor when you might be used to something else, but we think you get a lot more benefit out of having the three parts working together,” she told TechCrunch.

She added, “In Dark, you’re getting the benefit of your editor knowing how the language works. So you get really great autocomplete, and your infrastructure is set up for you as soon as you’ve written any code because we know exactly what is required.”

It’s certainly an intriguing proposition, but Chisa acknowledges that it will require evangelizing the methodology to programmers, who may be used to employing a particular set of tools to write their programs. She said the biggest selling point is that it removes so much of the complexity around deployment by bringing an integrated level of automation to the process.

She says there are three main benefits to Dark’s approach. In addition to providing automated infrastructure, which is itself a major plus, developers using Dark don’t have to worry about a deployment pipeline. “As soon as you write any piece of backend code in Dark, it is already hosted for you,” she explained. The last piece is that tracing is built right in as you code. “Because you’re using our infrastructure, you have traces available in your editor as soon as you’ve written any code,” she said.

Chisa’s co-founder and company CTO is Paul Biggar, who knows a thing or two about deployment, having helped found CircleCI, the CI/CD pioneering company.

As for that $3.5 million seed round, it was led by Cervin Ventures, with participation from Boldstart, Data Collective, Harrison Metal, Xfactor (Erica Brescia), Backstage, Nextview, Promus, Correlation, 122 West and Yubari.

Powered by WPeMatico

Before Tableau was the $15.7 billion key to Salesforce’s problems, it was a couple of founders arguing with a couple of venture capitalists over lunch about why its Series A valuation should be higher than $12 million pre-money.

Salesforce has generally been one to signify corporate strategy shifts through their acquisitions, so you can understand why the entire tech industry took notice when the cloud CRM giant announced its priciest acquisition ever last month.

The deal to acquire the Seattle-based data visualization powerhouse Tableau was substantial enough that Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff publicly announced it was turning Seattle into its second HQ. Tableau’s acquisition doesn’t just mean big things for Salesforce. With the deal taking place just days after Google announced it was paying $2.6 billion for Looker, the acquisition showcases just how intense the cloud wars are getting for the enterprise tech companies out to win it all.

The Exit is a new series at TechCrunch. It’s an exit interview of sorts with a VC who was in the right place at the right time but made the right call on an investment that paid off. [Have feedback? Shoot me an email at lucas@techcrunch.com]

Scott Sandell, a general partner at NEA (New Enterprise Associates) who has now been at the firm for 25 years, was one of those investors arguing with two of Tableau’s co-founders, Chris Stolte and Christian Chabot. Desperate to close the 2004 deal over their lunch meeting, he went on to agree to the Tableau founders’ demands of a higher $20 million valuation, though Sandell tells me it still feels like he got a pretty good deal.

NEA went on to invest further in subsequent rounds and went on to hold over 38% of the company at the time of its IPO in 2013 according to public financial docs.

I had a long chat with Sandell, who also invested in Salesforce, about the importance of the Tableau deal, his rise from associate to general partner at NEA, who he sees as the biggest challenger to Salesforce, and why he thinks scooter companies are “the worst business in the known universe.”

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Lucas Matney: You’ve been at this investing thing for quite a while, but taking a trip down memory lane, how did you get into VC in the first place?

Scott Sandell: The way I got into venture capital is a little bit of a circuitous route. I had an opportunity to get into venture capital coming out of Stanford Business School in 1992, but it wasn’t quite the right fit. And so I had an interest, but I didn’t have the right opportunity.

Powered by WPeMatico