Startups

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

If the sheer amount of information that we can tap into using the internet has made the world our oyster, then the huge success of Google is a testament to how lucrative search can be in helping to light the way through that data maze.

Now, in a sign of the times, a startup called Lucidworks, which has built an AI-based engine to help individual organizations provide personalised search services for their own users, has raised $100 million in funding. Lucidworks believes its approach can produce better and more relevant results than other search services in the market, and it plans to use the funding for its next stage of growth to become, in the words of CEO Will Hayes, “the world’s next important platform.”

The funding is coming from PE firm Francisco Partners and TPG Sixth Street Partners. Existing investors in the company include Top Tier Capital Partners, Shasta Ventures, Granite Ventures and Allegis Cyber.

Lucidworks has raised around $200 million in funding to date, and while it is not disclosing the valuation, the company says it has been doubling revenues each year for the last three and counts companies like Reddit, Red Hat, REI and the U.S. Census among some 400 others of its customers using its flagship product, Fusion. PitchBook notes that its last round in 2018 was at a modest $135 million, and my guess is that is up by quite some way.

The idea of building a business on search, of course, is not at all new, and Lucidworks works is in a very crowded field. The likes of Amazon, Google and Microsoft have built entire empires on search — in Google’s and Microsoft’s case, by selling ads against those search results; in Amazon’s case, by generating sales of items in the search results — and they have subsequently productised that technology, selling it as a service to others.

Alongside that are companies that have been building search-as-a-service from the ground up — like Elastic, Sumo Logic and Splunk (whose founding team, coincidentally, went on to found Lucidworks…) — both for back-office processes as well as for services that are customer-facing.

In an interview, Hayes said that what sets Lucidworks apart is how it uses machine learning and other AI processes to personalise those results after “sorting through mountains of data,” to provide enterprise information to knowledge workers, shopping results on an e-commerce site to consumers, data to wealth managers or whatever it is that is being sought.

Take the case of a shopping experience, he said by way of explanation. “If I’m on REI to buy hiking shoes, I don’t just want to see the highest-rated hiking shoes, or the most expensive,” he said.

The idea is that Lucidworks builds algorithms that bring in other data sources — your past shopping patterns, your location, what kind of walking you might be doing, what other people like you have purchased — to produce a more focused list of products that you are more likely to buy.

“Amazon has no taste,” he concluded, a little playfully.

Today, around half of Lucidworks’ business comes from digital commerce and digital content — searches of the kind described above for products, or monitoring customer search queries sites like Red Hat or Reddit — and half comes from knowledge worker applications inside organizations.

The plan will be to continue that proportion, while also adding other kinds of features — more natural language processing and more semantic search features — to expand the kinds of queries that can be made, and also cues that Fusion can use to produce results.

Interestingly, Hayes said that while it’s come up a number of times, Lucidworks doesn’t see itself ever going head-to-head with a company like Google or Amazon in providing a first-party search platform of its own. Indeed, that may be an area that has, for the time being at least, already been played out. Or it may be that we have turned to a time when walled gardens — or at least more targeted and curated experiences — are coming into their own.

“We still see a lot of runway in this market,” said Jonathan Murphy of Francisco Partners. “We were very attracted to the idea of next-generation search, on one hand serving internet users facing the pain of the broader internet, and on the other enterprises as an enterprise software product.”

Lucidworks, it seems, has also entertained acquisition approaches, although Hayes declined to get specific about that. The longer-term goal, he said, “is to build something special that will stay here for a long time. The likelihood of needing that to be a public company is very high, but we will do what we think is best for the company and investors in the long run. But our focus and intention is to continue growing.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Small satellite launch startup Vector has indefinitely shut down operations “in response a major change in financing,” the company confirmed. Co-founder and CEO Jim Cantrell has also been cut loose as part of the upset.

The news comes as a surprise to the space startup community, and apparently to its employees. The company lined up $70 million in funding late last year, and recently was announced as a qualified contestant in DARPA’s Launch Challenge. It even pulled in a multi-million dollar Air Force contract just last week.

That something must have gone awry with this latest funding is manifest. But just what, or who, is unclear. I’m contacting the venture firms in the round (Kodem, Morgan Stanley Alternative Investment Partners, Sequoia, Lightspeed and Shasta Ventures) and will update if anyone has any substantial comment.

The company offered the following statement, as well as confirming that Cantrell is out.

In response to a major change in financing, Vector has had to pause its operations. A core team is now evaluating options to complete the development of the company’s Vector R small launch vehicle while also supporting the Air Force and other government agencies on programs such as the recent ASLON-45 award.

Vector has been working on an orbital launch vehicle, the Vector-R, with a 60 kilogram maximum payload — a small rocket for small satellites, for which there is plenty of demand. A heavier version that could lift 290 kg was also under development.

Plans were to demonstrate an orbital launch by the end of 2019, but as yet that has not occurred; a suborbital launch was also planned for sometime this summer, but that too is yet to happen.

Perhaps the launch delays were the cause of the funding problems, or perhaps the funding problems led to launch delays. I’ll update this story as soon as more details are available.

Powered by WPeMatico

Hello and welcome back to Startups Weekly, a weekend newsletter that dives into the week’s noteworthy startups and venture capital news. Before I jump into today’s topic, let’s catch up a bit. Last week, I wrote about DoorDash’s acquisition of Caviar, which no one saw coming. Before that, I jotted down some notes on SoftBank’s second Vision Fund.

Remember, you can send me tips, suggestions and feedback to kate.clark@techcrunch.com or on Twitter @KateClarkTweets. If you don’t subscribe to Startups Weekly yet, you can do that here.

Alternative funding mechanisms, like Clearbanc’s revenue share model, may be on the rise but most Silicon Valley startups still turn to venture capital to get their company off the ground. As I’ve previously said in this newsletter, VC spending in 2019 is reaching record-highs, already surpassing $62 billion. Angel investment, for its part, also continues to occupy a meaningful portion of private investment. So far this year, individual angels and angel groups in the U.S. have doled out $10 billion to startups.

Angel investors are not traditional venture capitalists bogged down by processes, quotas and fund economics. Rather, they’re deep-pocketed former operators (often) with expansive networks. For some, their capital is superior to VCs; for others, a VC’s ability to write larger checks and participate in additional fundings as their company grows makes VC the only viable option.

So how do early-stage startups decide who’s money to take (if they have that luxury)? Here’s what Jana Messerschmidt, both an investor at Lightspeed Venture Partners and a founding partner of the angel network #ANGELS, had to say: “It’s dependent on who the individual angel is, as well as who the individual partner is. In these frothier times, I encourage founders to interview investors who take a slot on their cap table with the same rigor they would a potential employee.”

What are the advantages and disadvantages of taking money from an established venture capital fund vs. an established angel investor?

— Kate Clark (@KateClarkTweets) August 6, 2019

Ben Ling, an early Facebook executive who spent years angel investing only to launch his own institutional venture capital fund, Bling Capital, tells TechCrunch the plus side of angel investors is that they are oftentimes less sensitive to valuations. Angels, while they can’t usually invest as much capital as a VC, tend to offer better terms and be approving of less rigid deal structures.

But being an investor isn’t an angel’s full-time job, typically. The limited amount of time an angel can give each company may be problematic for a founder seeking mentorship but a non-issue for a more experienced founder, who is simply seeking an individual passionate about her or his vision.

Given the rise in venture capital investment overall, more founders and former operators are running into wealth and opting to try on the VC hat for size. And more and more, those people are becoming professional investors with an appetite for a bigger pool of capital. Ling, as mentioned, decided last year to raise his first institutional fund, a $60 million effort, for example: “I think it’s rare for super angels to ‘beat’ firms for most regular financings but it certainly can happen,” Ling tells TechCrunch.

Presumably, that’s why he and many others (Cyan Banister, Keith Rabois, Ron Conway, James Currier) made the switch to “real” VC — to win over the best deals. As angels turn into VCs, whether your startup’s money came from one person’s wallet or an institutional fund matters a whole lot less. Just make sure you have good people investing in your company, and while you are it, make sure they’re diverse too.

That’s all for now… Onto the news.

Bloomberg reported Friday that WeWork was expected to make its IPO filing available next week. Soon, we can all finally get an inside look at the co-working giant’s financials. A reminder, WeWork was last valued at an eye-popping $47 billion and it wants to raise some $3.5 billion in the IPO. Skeptical? Me too.

If you enjoy this newsletter, be sure to check out TechCrunch’s venture-focused podcast, Equity. In this week’s episode, available here, Equity co-host Alex Wilhelm and I discuss a new trend in venture capital: sperm storage startups. Equity drops every Friday at 6:00 am PT, so subscribe to us on Apple Podcasts, Overcast and Spotify.

Airbnb announced its acquisition of Urbandoor, a platform that offers extended stays to corporate clients, earlier this week. The terms of the deal were not disclosed, though an SEC filing connected with the deal emerged Friday, indicating the deal was worth more than $80 million in what’s likely a combination of cash and stock. We’ve got all the details on the deal here.

Now it’s time for your weekly reminder to sign up for Extra Crunch. For a low price, you can learn more about the startups and venture capital ecosystem through exclusive deep dives, Q&As, newsletters, resources and recommendations and fundamental startup how-to guides. Here’s a passage from my personal favorite EC post of the week:

“Why is tech still aiming for the healthcare industry? It seems full of endless regulatory hurdles or stories of misguided founders with no knowledge of the space, running headlong into it, only to fall on their faces. Theranos is a prime example of a founder with zero health background or understanding of the industry — and just look what happened there! The company folded not long after founder Elizabeth Holmes came under criminal investigation and was barred from operating in her own labs for carelessly handling sensitive health data and test results…”

Read the rest of Sarah Buhr’s piece, ‘What leading healthtech VCs are interested in,’ here.

Powered by WPeMatico

You may not have heard of Kobalt before, but you probably engage with the music it oversees every day, if not almost every hour. Combining a technology platform to better track ownership rights and royalties of songs with a new approach to representing musicians in their careers, Kobalt has risen from the ashes of the 2000 dot-com bubble to become a major player in the streaming music era. It is the leading alternative to incumbent music publishers (who represent songwriters) and is building a new model record label for the growing “middle class’ of musicians around the world who are stars within niche audiences.

Having predicted music’s digital upheaval early, Kobalt has taken off as streaming music has gone mainstream across the US, Europe, and East Asia. In the final quarter of last year, it represented the artists behind 38 of the top 100 songs on U.S. radio.

Along the way, it has secured more than $200 million in venture funding from investors like GV, Balderton, and Michael Dell, and its valuation was last pegged at $800 million. It confirmed in April that it is raising another $100 million to boot. Kobalt Music Group now employs over 700 people in 14 offices, and GV partner Avid Larizadeh Duggan even left her firm to become Kobalt’s COO.

How did a Swedish saxophonist from the 1980s transform into a leading entrepreneur in music’s digital transformation? Why are top technology VCs pouring money into a company that represents a roster of musicians? And how has the rise of music streaming created an opening for Kobalt to architect a new approach to the way the industry works?

Gaining an understanding of Kobalt and its future prospects is a vehicle for understanding the massive change underway across the global music industry right now and the opportunities that is and isn’t creating for entrepreneurs.

This article is Part 1 of the Kobalt EC-1, focused on the company’s origin story and growth. Part 2 will look at the company’s journey to create a new model for representing songwriters and tracking their ownership interests through the complex world of music royalties. Part 3 will look at Kobalt’s thesis about the rise of a massive new middle class of popular musicians and the record label alternative it is scaling to serve them.

It’s tough to imagine a worse year to launch a music company than 2000. Willard Ahdritz, a Swede living in London, left his corporate consulting job and sold his home for £200,000 to fully commit to his idea of a startup collecting royalties for musicians. In hindsight, his timing was less than impeccable: he launched Kobalt just as Napster and music piracy exploded onto the mainstream and mere months before the dot-com crash would wipe out much of the technology industry.

The situation was dire, and even his main seed investor told him he was doomed once the market crashed. “Eating an egg and ham sandwich…have you heard this saying? The chicken is contributing but the pig is committed,” Ahdritz said when we first spoke this past April (he has an endless supply of sayings). “I believe in that — to lose is not an option.”

Entrepreneurial hardship though is something that Ahdritz had early experience with. Born in Örebro, a city of 100,000 people in the middle of Sweden, Ahdritz spent a lot of time as a kid playing in the woods, which also holding dual interests in music and engineering. The intersection of those two converged in the synthesizer revolution of early electronic music, and he was fascinated by bands like Kraftwerk.

Powered by WPeMatico

Much of Silicon Valley mythology is centered on the founder-as-hero narrative. But historically, scientific founders leading the charge for bio companies have been far less common.

Developing new drugs is slow, risky and expensive. Big clinical failures are all too common. As such, bio requires incredibly specialized knowledge and experience. But at the same time, the potential for value creation is enormous today more than ever with breakthrough new medicines like engineered cell, gene and digital therapies.

What these breakthroughs are bringing along with them are entirely new models — of founders, of company creation, of the businesses themselves — that will require scientists, entrepreneurs and investors to reimagine and reinvent how they create bio companies.

In the past, biotech VC firms handled this combination of specialized knowledge + binary risk + outsized opportunity with a unique “company creation” model. In this model, there are scientific founders, yes; but the VC firm essentially founded and built the company itself — all the way from matching a scientific advance with an unmet medical need, to licensing IP, to having partners take on key roles such as CEO in the early stages, to then recruiting a seasoned management team to execute on the vision.

Image: PASIEKA/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Getty Images

You could call this the startup equivalent of being born and bred in captivity — where great care and feeding early in life helps ensure that the company is able to thrive. Here the scientific founders tend to play more of an advisory role (usually keeping day jobs in academia to create new knowledge and frontiers), while experienced “drug hunters” operate the machinery of bringing new discoveries to the patient’s bedside. This model’s core purpose is to bring the right expertise to the table to de-risk these incredibly challenging enterprises — nobody is born knowing how to make a medicine.

But the ecosystem this model evolved from is evolving itself. Emerging fields like computational biology and biological engineering have created a new breed of founder, native to biology, engineering and computer science, that are already, by definition, the leading experts in their fledgling fields. Their advances are helping change the industry, shifting drug discovery away from a highly bespoke process — where little knowledge carries over from the success or failure of one drug to the next — to a more iterative, building-block approach like engineering.

Take gene therapy: once we learn how to deliver a gene to a specific cell in a given disease, it is significantly more likely we will be able to deliver a different gene to a different cell for another disease. Which means there’s an opportunity not only for novel therapies but also the potential for new business models. Imagine a company that provides gene delivery capability to an entire industry — GaaS: gene-delivery as a service!

Once a founder has an idea, the costs of testing it out have changed too. The days of having to set up an entire lab before you could run your first experiments are gone. In the same way that AWS made starting a tech company vastly faster and easier, innovations like shared lab spaces and wetlab accelerators have dramatically reduced the cost and speed required to get a bio startup off the ground. Today it costs thousands, not millions, for a “killer experiment” that will give a founding team (and investors) early conviction.

What all this amounts to is scientific founders now have the option of launching bio companies without relying on VCs to create them on their behalf. And many are. The new generation of bio companies being launched by these founders are more akin to being born in the wild. It isn’t easy; in fact, it’s a jungle out there, so you need to make mistakes, learn quickly, hone your instincts, and be well-equipped for survival. On the other hand, given the transformative potential of engineering-based bio platforms, the cubs that do survive can grow into lions.

Image via Getty Images / KTSDESIGN/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

So, which is better for a bio startup today: to be born in the wild — with all the risk and reward that entails — or to be raised in captivity

The “bred in captivity” model promises sureness, safety, security. A VC-created bio company has cache and credibility right off the bat. Launch capital is essentially guaranteed. It attracts all-star scientists, executives and advisors — drawn by the balance of an innovative, agile environment and a well-funded, well-connected support network. I was fortunate enough to be an early executive in one of these companies, giving me the opportunity to work alongside industry luminaries and benefit from their well-versed knowledge of how to build a world-class bio company with all its complex component parts: basic, translational, clinical research, from scratch. But this all comes at a price.

Because it’s a heavy lift for the VCs, scientific founders are usually left with a relatively small slug of equity — even founding CEOs can end up with ~5% ownership. While these companies often launch with headline-grabbing funding rounds of $50m or above, the capital is tranched — meaning money is doled out as planned milestones are achieved. But the problem is, things rarely go according to plan. Tranched capital can be a safety net, but you can get tangled in that net if you miss a milestone.

Being born in the wild, on the other hand, trades safety for freedom. No one is building the company on your behalf; you’re in charge, and you bear the risk. As a recent graduate, I co-founded a company with Harvard geneticist George Church. The company was bootstrapped — a funding strategy that was more famine than feast — but we were at liberty to try new things and run (un)controlled experiments like sequencing heavy metal wildman Ozzy Osbourne.

It was the early, Wild West days of the genomics revolution and many of the earliest biotech companies mirrored that experience — they weren’t incepted by VCs; they were created by scrappy entrepreneurs and scientists-turned-CEO. Take Joshua Boger, organic chemist and founder of Vertex Pharmaceuticals: starting in 1989 his efforts to will into existence a new way to develop drugs, thrillingly captured in Barry Werth’s The Billion-Dollar Molecule and its sequel The Antidote in all its warts and nail-biting glory, ultimately transformed how we treat HIV, hepatitis C and cystic fibrosis.

Today we’re in a back-to-the-future moment and the industry is being increasingly pushed forward by this new breed of scientist-entrepreneur. Students-turned-founder like Diego Rey of in vitro diagnostics company GeneWEAVE and Ramji Srinivasan of clinical laboratory Counsyl helped transform how we diagnose disease and each led their companies to successful acquisitions by larger rivals.

Popular accelerators like Y Combinator and IndieBio are filled with bio companies driven by this founder phenotype. Ginkgo Bioworks, the first bio company in Y Combinator and today a unicorn, was founded by Jason Kelly and three of his MIT biological engineering classmates, along with former MIT professor and synthetic biology legend Tom Knight. The company is not only innovating new ways to program biology in order to disrupt a broad range of industries, but it’s also pioneering an innovative conglomerate business model it has dubbed the “Berkshire for biotech.”

Like the Ginkgo founders, Alec Nielsen and Raja Srinivas launched their startup Asimov, an ambitious effort to program cells using genetic circuits, shortly after receiving their PhDs in biological engineering from MIT. And, like Boger, renowned machine learning Stanford professor Daphne Koller is working to once again transform drug discovery as the founder and CEO of Instiro.

Just like making a medicine, no one is born knowing how to build a company. But in this new world, these technical founders with deep domain expertise may even be more capable of traversing the idea maze than seasoned operators. Engineering-based platforms have the potential to create entirely new applications with unprecedented productivity, creating opportunities for new breakthroughs, novel business models, and new ways to build bio companies. The well-worn playbooks may be out of date.

Founders that choose to create their own companies still need investors to scrub in and contribute to the arduous labor of company-building — but via support, guidance, and with access to networks instead. And like this new generation of founders, bio investors today need to rethink (and re-value) the promise of the new, and still appreciate the hard-earned wisdom of the old. In other words, bio investors also need to be multidisciplinary. And they need to be comfortable with a different kind of risk: backing an unproven founder in a new, emerging space. As a founder, if you’re willing to take your chances in the wild, you should have an investor that understands you, believes in you, can support you and, importantly, is willing to dream big with you.

Powered by WPeMatico

It’s down to the wire folks. Today’s the last day you can save $100 on your ticket to TC Sessions: Enterprise 2019, which takes place on September 5 at the Yerba Buena Center in San Francisco. The deadline expires in mere hours — at 11:59 p.m. (PT). Get the best possible price and buy your early-bird ticket right now.

We expect more than 1,000 attendees representing the enterprise software community’s best and brightest. We’re talking founders of companies in every stage and CIOs and systems architects from some of the biggest multinationals. And, of course, managing partners from the most influential venture and corporate investment firms.

Take a look at just some of the companies joining us for TC Sessions: Enterprise: Bain & Company, Box, Dell Technologies Capital, Google, Oracle, SAP and SoftBank. Let the networking begin!

You can expect a full day of main-stage interviews and panel discussions, plus break-out sessions and speaker Q&As. TechCrunch editors will dig into the big issues enterprise software companies face today along with emerging trends and technologies.

Data, for example, is a mighty hot topic, and you’ll hear a lot more about it during a session entitled, Innovation Break: Data – Who Owns It?: Enterprises have historically competed by being closed entities, keeping a closed architecture and innovating internally. When applying this closed approach to the hottest new commodity, data, it simply does not work anymore. But as enterprises, startups and public institutions open themselves up, how open is too open? Hear from leaders who explore data ownership and the questions that need to be answered before the data floodgates are opened. Sponsored by SAP .

If investment is on your mind, don’t miss the Investor Q&A. Some of greatest investors in enterprise will be on hand to answer your burning questions. Want to know more? Check out the full agenda.

Maximize your last day of early-bird buying power and take advantage of the group discount. Buy four or more tickets at once and save 20%. Here’s a bonus. Every ticket you buy to TC Sessions: Enterprise includes a free Expo Only pass to TechCrunch Disrupt SF on October 2-4.

It’s now o’clock startuppers. Your opportunity to save $100 on tickets to TC Sessions: Enterprise ends tonight at precisely 11:59 p.m. (PT). Buy your early-bird tickets now and join us in September!

Is your company interested in sponsoring or exhibiting at TC Sessions: Enterprise? Contact our sponsorship sales team by filling out this form.

Powered by WPeMatico

As privacy regulations like GDPR and the California Consumer Privacy Act proliferate, more startups are looking to help companies comply. Enter Preclusio, a member of the Y Combinator Summer 2019 class, which has developed a machine learning-fueled solution to help companies adhere to these privacy regulations.

“We have a platform that is deployed on-prem in our customer’s environment, and helps them identify what data they’re collecting, how they’re using it, where it’s being stored and how it should be protected. We help companies put together this broad view of their data, and then we continuously monitor their data infrastructure to ensure that this data continues to be protected,” company co-founder and CEO Heather Wade told TechCrunch.

She says that the company made a deliberate decision to keep the solution on-prem. “We really believe in giving our clients control over their data. We don’t want to be just another third-party SaaS vendor that you have to ship your data to,” Wade explained.

That said, customers can run it wherever they wish, whether that’s on-prem or in the cloud in Azure or AWS. Regardless of where it’s stored, the idea is to give customers direct control over their own data. “We are really trying to alert our customers to threats or to potential privacy exceptions that are occurring in their environment in real time, and being in their environment is really the best way to facilitate this,” she said.

The product works by getting read-only access to the data, then begins to identify sensitive data in an automated fashion using machine learning. “Our product automatically looks at the schema and samples of the data, and uses machine learning to identify common protected data,” she said. Once that process is completed, a privacy compliance team can review the findings and adjust these classifications as needed.

Wade, who started the company in March, says the idea formed at previous positions where she was responsible for implementing privacy policies and found there weren’t adequate solutions on the market to help. “I had to face the challenges first-hand of dealing with privacy and compliance and seeing how resources were really taken away from our engineering teams and having to allocate these resources to solving these problems internally, especially early on when GDPR was first passed, and there really were not that many tools available in the market,” she said.

Interestingly Wade’s co-founder is her husband, John. She says they deal with the intensity of being married and startup founders by sticking to their areas of expertise. He’s the marketing person and she’s the technical one.

She says they applied to Y Combinator because they wanted to grow quickly, and that timing is important with more privacy laws coming online soon. She has been impressed with the generosity of the community in helping them reach their goals. “It’s almost indescribable how generous and helpful other folks who’ve been through the YC program are to the incoming batches, and they really do have that spirit of paying it forward,” she said.

Powered by WPeMatico

Glow is a new startup that says it wants to help podcasters build media business.

That’s something co-founder and CEO Amira Valliani said she tried to do herself. After a career that included working in the Obama White House and getting an MBA from Wharton, she launched a podcast covering local elections in Cambridge, Mass., and she said that after the initial six episodes, she struggled to find a sustainable business model.

Valliani (pictured above with her co-founder and chief product officer Brian Elieson) recalled thinking, “Well, I got this one grant and I’d love to do more, but I need to figure out a way to pay for it.” She realized that advertising didn’t make sense, but when a listener expressed interest in paying her directly, none of the existing platforms made it easy.

“I just couldn’t figure it out,” she said. “I felt an acute need, and I thought, ‘Are there other people out there who haven’t been able to figure out how to do it, because the lift is just too high?’ ”

That’s the need Glow tries to address with its first product — allowing podcasters to create paid subscriptions. To do that, podcasters create a subscription page on the Glow site, where they can accept payments and then allow listeners to access paywalled content from the podcast app of their choice.

Glow started testing the product with the startup-focused podcast Acquired, which is now bringing in $35,000 in subscription fees through Glow. More recently, it’s signed up the Techmeme Ride Home, Twenty Thousand Hertz, The Newsworthy and others.

When asked about the broader landscape of podcast startups (including several that support paid subscriptions), Valliani said there are three main problems that podcasters face: hosting, monetization and distribution.

Hosting, she said, is “largely a solved problem,” so Glow is starting out by trying to “solve for monetization through the direct relationship with listeners.” Eventually, it could move into distribution, though that doesn’t mean launching a Glow podcast app: “For us, we think distribution means helping podcasts grow their audience.”

The startup announced today that it has raised $2.3 million in seed funding. The round was led by Greycroft, with participation from Norwest Venture Partners, PSL Ventures, WndrCo and Revolution’s Rise of the Rest Seed Fund, as well as individual investors including Nas and Electronic Arts CTO Ken Moss.

“Our first hire after this funding round will be someone focused on podcast success,” Valliani said. “Of course, we’re going to build the product [but we’re] doubling down on this market; we better make sure that [podcasters] are prepared to launch programs that are as successful as possible.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Following many months of pressure, DoorDash, one of the most frequently used food delivery apps in the U.S., said late last month that it was finally changing its tipping policy to pass along to workers 100% of tips, rather than employ some of that money toward defraying its own costs.

The move was a step in the right direction, but as a New York Times piece recently underscored, there are many remaining challenges for food delivery couriers, including not knowing where a delivery is going until a worker picks it up (Uber Eats), having just seconds to decide whether or not to accept an order (Postmates) and not being guaranteed a minimum wage (Deliveroo) — not to mention the threat of delivery robots taking their jobs.

It’s a big enough problem that a young, nine-person startup called Dumpling has decided to tackle it directly. Its big idea: turn today’s delivery workers into “solopreneurs” who build their own book of clients and keep much more of the money.

It newly has $3 million in backing from two venture firms that know the gig economy well, too: Floodgate, an early investor in Lyft (firm co-founder Ann Miura-Ko is on Lyft’s board), and Fuel Capital, where TaskRabbit founder Leah Busque is now a general partner.

We talked with Dumpling’s co-founders and co-CEOs earlier this week to learn more about the company and how viable it might be. Nate D’Anna spent eight years as a director of corporate development at Cisco; Joel Shapiro spent more than 13 years with National Instruments, where he held a variety of roles, including as a marketing director focused on emerging markets.

National Instruments, based in Austin, is also where Shapiro and D’Anna first met back in 2002. Our chat, edited lightly for length, follows:

TC: You started working together out of college. What prompted you to come together to start Dumpling?

JS: We’d stayed good friends as we’d done different things with our careers, but we were both seeing rising inequality happening at companies and within their workforces, and we were both interested in using our [respective] background and experiences to try and make a difference.

ND: When we were first started, Dumpling wasn’t a platform for people to start their own business. It was a place for people to voice opinions — kind of like a Glassdoor for workers with hourly jobs, including in retail. What jumped out at us was how many gig workers began using the platform to talk about the horrible ways they were being treated, not having a traditional boss and not being protected by traditional policies.

TC: At what point did you think you were onto a separate opportunity?

ND: We knew that a mission-driven company that’s trying to do good by people who’ve been exploited by Silicon Valley companies has to be profitable. I was an investor at Cisco, and I was very clear that the money side has to work. So we started talking with gig workers and we asked, ‘Why are you working for a terrible company where you’re getting injured, where you’re getting penalized for not taking the next job?’ And the response was ‘money.’ It was, ‘I need to be able to buy these groceries and I don’t want to put them on my own credit card.’ That was an epiphany for us. If the biggest pain point to running these businesses is working capital and we can solve that — if business owners will pay for access to capital and for tools that help them run their business — that clicked for us.

TC: A big part of your premise is that while gig economy companies have anonymized people as best they can, there’s a meaningful segment of services where a stranger or a robot isn’t going to work.

JS: Shoppers for gig companies often hear, ‘When you [specifically] come, it makes my day,’ so our philosophy was to build a platform that supports the person. When you run a business and build a clientele that you get to know, you’re incentivized for that [client] to have a good experience. So we wondered, how do we provide tools for someone who has done personal shopping and who not only needs funds to shop but also help with marketing and a website and training so they can promote their services?

ND: We also realized that to help business owners succeed that we needed to lower the transaction cost for them to find customers, so we created a marketplace where shoppers can look at reviews, understand different shoppers’ knowledge regarding when it comes to various specialties and stores, then help match them.

TC: How many shoppers are now running their own businesses on Dumpling and what do they get from you exactly?

JS: More than 500 across the country are operating in 37 states. And we want to give them everything they need. A big part of that is capital, so we give [them] a credit card, then it’s effectively the operational support, including order management, customer relationship functionality, customer communication, a storefront, an app that they can use to run their business from their phone. . .

TC: What about insurance, tax help, that sort of stuff?

ND: A lot of VCs pushed us in that direction. The good news is a lot of companies are coming up to provide those ancillary services, and we’ll eventually partner with them if you want to export your data to Intuit or someone else. Right now, we’re really focused on [shoppers’] core business, helping then to operate it, to find customers, that’s our sweet spot for the immediate future.

TC: What are you charging? Who are you charging?

JS: A subscription model is an obvious way for us to go at some point, but right now, because we’re in the transaction flow, we’re taking a percentage of each transaction. The [solopreneuer] pays us $5 per transaction as a platform fee; the shopper pays us 5% atop the delivery fee set by the [person who is delivering their goods]. So if someone spends $100 on groceries, that customer pays us $5, and the shopper pays us $5 and the shopper gets that delivery fee, plus his or her tip.

The vast amount goes to the shopper, unlike with today’s model [wherein the vast majority goes to delivery companies]. Our average shopper is bringing home $32 in earnings per order, roughly three times as much as when they work for other grocery delivery apps. I think that’s partly because we communicate to [shoppers] that they are supporting local businesses and local entrepreneurs and they are receiving an average tip of 17% on their orders. But also, when you know your shopper and that person gets to know your preferences, you’re much more comfortable ordering non-perishables, like produce picked the way you like. That leads to huge order sizes, which is another reason that average earnings are higher.

TC: You’re fronting the cost for groceries. Is that money coming from your venture funding? Do you have a debt facility?

ND: We don’t. The money moves so fast. The shoppers are using the card to shop, then getting the money back again, so the cycle time is quick. It’s two days, not six months.

TC: How does this whole thing scale? Are you collecting data that you hope will inform future products?

ND: We definitely want to use tech to empower [shoppers] instead of control them. But [our CTO and third co-founder Tom Schoellhammer] came from Google doing search there, and eventually we [expect to] recommend similar stores, or [extend into] beauty or pet other local services. Grocery delivery is one obvious place where the market is broken, but where you want a trusted person involved, and you’re in the flow when people are looking for something [the opportunity opens up]. Shoppers’ knowledge of their local operation zone can be leveraged much more.

Powered by WPeMatico

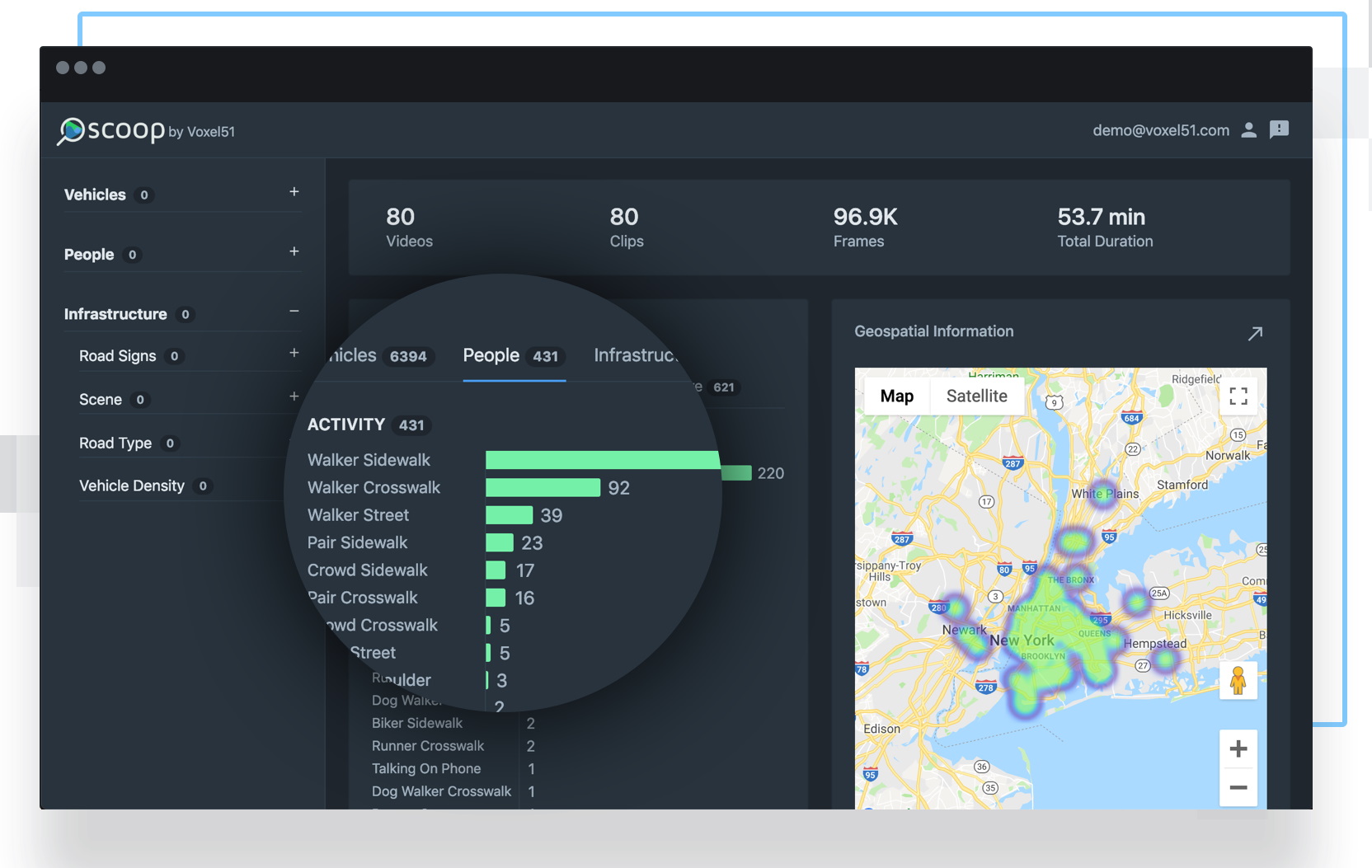

Many companies and municipalities are saddled with hundreds or thousands of hours of video and limited ways to turn it into usable data. Voxel51 offers a machine learning-based option that chews through video and labels it, not just with simple image recognition but with an understanding of motions and objects over time.

Annotating video is an important task for a lot of industries, the most well-known of which is certainly autonomous driving. But it’s also important in robotics, the service and retail industries, for police encounters (now that body cams are becoming commonplace) and so on.

It’s done in a variety of ways, from humans literally drawing boxes around objects every frame and writing what’s in it to more advanced approaches that automate much of the process, even running in real time. But the general rule with these is that they’re done frame by frame.

A single frame is great if you want to tell how many cars are in an image, or whether there’s a stop sign, or what a license plate reads. But what if you need to tell whether someone is walking or stepping out of the way? What about whether someone is waving or throwing a rock? Are people in a crowd going to the right or left, generally? This kind of thing is difficult to infer from a single frame, but looking at just two or three in succession makes it clear.

That fact is what startup Voxel51 is leveraging to take on the established competition in this space. Video-native algorithms can do some things that single-frame ones can’t, and where they do overlap, the former often does it better.

Voxel51 emerged from computer vision work done by its co-founders, CEO Jason Corso and CTO Brian Moore, at the University of Michigan. The latter took the former’s computer vision class and eventually the two found they shared a desire to take ideas out of the lab.

“I started the company because I had this vast swath of research,” Corso said, “and the vast majority of services that were available were focused on image-based understanding rather than video-based understanding. And in almost all instances we’ve seen, when we use a video-based model we see accuracy improvements.”

While any old off-the-shelf algorithm can recognize a car or person in an image, it takes much more savvy to make something that can, for example, identify merging behaviors at an intersection, or tell whether someone has slipped between cars to jaywalk. In each of those situations the context is important and multiple frames of video are needed to characterize the action.

“When we process data we look at the spacio-temporal volume as a whole,” said Corso. “Five, 10, 30 frames… our models figure out how far behind and forward it should look to find a robust inference.”

In other, more normal words, the AI model isn’t just looking at an image, but at relationships between many images over time. If it’s not quite sure whether a person in a given frame is crouching or landing from a jump, it knows that it can scrub a little forward or backward to find the information that will make that clear.

And even for more ordinary inference tasks like counting the cars in the street, that data can be double-checked or updated by looking back or skipping ahead. If you can only see five cars because one’s big and blocks a sixth, that doesn’t change the fact that there are six cars. Even if every frame doesn’t show every car, it still matters for, say, a traffic monitoring system.

The natural objection to this is that processing 10 frames to find out what a person is doing is more expensive, computationally speaking, than processing a single frame. That’s certainly true if you are treating it like a series of still images, but that’s not how Voxel51 does it.

“We get away with it by processing fewer pixels per frame,” Corso explained. “The total amount of pixels we process might be the same or less as a single frame, depending on what we want it to do.”

For example, on video that needs to be closely examined but speed isn’t a concern (like a backlog of traffic cam data), it can expend all the time it needs on each frame. But for a case where the turnaround needs to be quicker, it can do a fast, real-time pass to identify major objects and motions, then go back through and focus on the parts that are the most important — not the unmoving sky or parked cars, but people and other known objects.

The platform is highly parameterized and naturally doesn’t share the limitations of human-driven annotation (though the latter is still the main option for highly novel applications where you’d have to build a model from scratch).

“You don’t have to worry about, is it annotator A or annotator B, and our platform is a compute platform, so it scales on demand,” said Corso.

They’ve packed everything into a drag-and-drop interface they call Scoop. You drop in your data — videos, GPS, things like that — and let the system power through it. Then you have a browsable map that lets you enumerate or track any number of things: types of signs, blue BMWs, red Toyotas, right turn only lanes, people walking on the sidewalk, people bunching up at a crosswalk, etc. And you can combine categories, in case you’re looking for scenes where that blue BMW was in a right turn only lane.

Each sighting is attached to the source video, with bounding boxes laid over it indicating the locations of what you’re looking for. You can then export the related videos, with or without annotations. There’s a demo site that shows how it all works.

It’s a little like Nexar’s recently announced Live Maps, though obviously also quite different. That two companies can pursue AI-powered processing of massive amounts of street-level video data and still be distinct business propositions indicates how large the potential market for this type of service is.

Despite its street-feature smarts, Voxel51 isn’t going after self-driving cars to start. Companies in that space, like Waymo and Toyota, are pursuing fairly narrow, vertically oriented systems that are highly focused on identifying objects and behaviors specific to autonomous navigation. The priorities and needs are different from, say, a security firm or police force that monitors hundreds of cameras at once — and that’s where the company is headed right now. That’s consistent with the company’s pre-seed funding, which came from a NIST grant in the public safety sector.

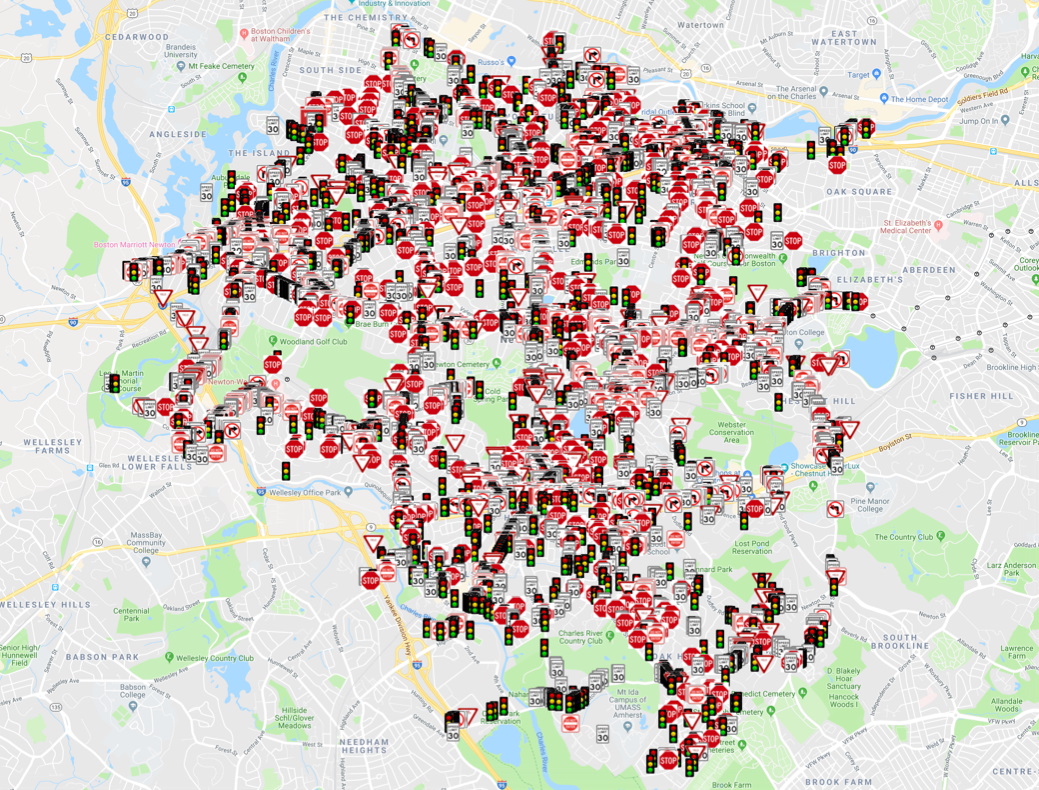

Built with no human intervention from 250 hours of video, a sign/signal map like this would be helpful to many a municipality

“The first phase of go to market is focusing on smart cities and public safety,” Corso said. “We’re working with police departments that are focused on citizen safety. So the officers want to know, is there a fire breaking out, or is a crowd gathering where it shouldn’t be gathering?”

“Right now it’s an experimental pilot — our system runs alongside Baltimore’s CitiWatch,” he continued, referring to a crime-monitoring surveillance system in the city. “They have 800 cameras, and five or six retired cops that sit in a basement watching those — so we help them watch the right feed at the right time. Feedback has been exciting: When [CitiWatch overseer Major Hood] saw the output of our model, not just the person but the behavior, arguing or fighting, his eyes lit up.”

Now, let’s be honest — it sounds a bit dystopian, doesn’t it? But Corso was careful to note that they are not in the business of tracking individuals.

“We’re primarily privacy-preserving video analytics; we have no ability or interest in running face identification. We don’t focus on any kind of identity,” he said.

It’s good that the priority isn’t on identity, but it’s still a bit of a scary capability to be making available. And yet, as anyone can see, the capability is there — it’s just a matter of making it useful and helpful rather than simply creepy. While one can imagine unethical uses like cracking down on protestors, it’s also easy to imagine how useful this could be in an Amber or Silver alert situation. Bad guy in a beige Lexus? Boom, last seen here.

At any rate, the platform is impressive and the computer vision work that went into it even more so. It’s no surprise that the company has raised a bit of cash to move forward. The $2 million seed round was led by eLab Ventures, a Palo Alto and Ann Arbor-based VC firm, and the company earlier attracted the $1.25 million grant from NIST mentioned earlier.

The money will be used for the expected purposes, establishing the product, building out support and the non-technical side of the company and so on. The flexible pricing and near-instant (in video processing terms) results seem like something that will drive adoption fairly quick, given the huge volumes of untapped video out there. Expect to see more companies like Corso and Moore’s as the value of that video becomes clear.

Powered by WPeMatico