Startups

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Data science is the name of the game these days for companies that want to improve their decision making by tapping the information they are already amassing in their apps and other systems. And today, a startup called Mode Analytics, which has built a platform incorporating machine learning, business intelligence and big data analytics to help data scientists fulfill that task, is announcing $33 million in funding to continue making its platform ever more sophisticated.

Most recently, for example, the company has started to introduce tools (including SQL and Python tutorials) for less technical users, specifically those in product teams, so that they can structure queries that data scientists can subsequently execute faster and with more complete responses — important for the many follow-up questions that arise when a business intelligence process has been run. Mode claims that its tools can help produce answers to data queries in minutes.

This Series D is being led by SaaS specialist investor H.I.G. Growth Partners, with previous investors Valor Equity Partners, Foundation Capital, REV Venture Partners and Switch Ventures all participating. Valor led Mode’s Series C in February 2019, while Foundation and REV respectively led its A and B rounds.

Mode is not disclosing its valuation, but co-founder and CEO Derek Steer confirmed in an interview that it was “absolutely” an up-round.

For some context, PitchBook notes that last year its valuation was $106 million. The company now has a customer list that it says covers 52% of the Forbes 500, including Anheuser-Busch, Zillow, Lyft, Bloomberg, Capital One, VMware and Conde Nast. It says that to date it has processed 830 million query runs and 170 million notebook cell runs for 300,000 users. (Pricing is based on a freemium model, with a free “Studio” tier and Business and Enterprise tiers priced based on size and use.)

Mode has been around since 2013, when it was co-founded by Steer, Benn Stancil (Mode’s current president) and Josh Ferguson (initially the CTO and now chief architect).

Steer said the impetus for the startup came out of gaps in the market that the three had found through years of experience at other companies.

Specifically, when all three were working together at Yammer (they were early employees and stayed on after the Microsoft acquisition), they were part of a larger team building custom data analytics tools for Yammer. At the time, Steer said Yammer was paying $1 million per year to subscribe to Vertica (acquired by HP in 2011) to run it.

They saw an opportunity to build a platform that could provide similar kinds of tools — encompassing things like SQL Editors, Notebooks and reporting tools and dashboards — to a wider set of users.

“We and other companies like Facebook and Google were building analytics internally,” Steer recalled, “and we knew that the world wanted to work more like these tech companies. That’s why we started Mode.”

All the same, he added, “people were not clear exactly about what a data scientist even was.”

Indeed, Mode’s growth so far has mirrored that of the rise of data science overall, as the discipline of data science, and the business case for employing data scientists to help figure out what is “going on” beyond the day to day, getting answers by tapping all the data that’s being amassed in the process of just doing business. That means Mode’s addressable market has also been growing.

But even if the trove of potential buyers of Mode’s products has been growing, so has the opportunity overall. There has been a big swing in data science and big data analytics in the last several years, with a number of tech companies building tools to help those who are less technical “become data scientists” by introducing more intuitive interfaces like drag-and-drop features and natural language queries.

They include the likes of Sisense (which has been growing its analytics power with acquisitions like Periscope Data), Eigen (focusing on specific verticals like financial and legal queries), Looker (acquired by Google) and Tableau (acquired by Salesforce).

Mode’s approach up to now has been closer to that of another competitor, Alteryx, focusing on building tools that are still aimed primarily at helping data scientists themselves. You have any number of database tools on the market today, Steer noted, “Snowflake, Redshift, BigQuery, Databricks, take your pick.” The key now is in providing tools to those using those databases to do their work faster and better.

That pitch and the success of how it executes on it is what has given the company success both with customers and investors.

“Mode goes beyond traditional Business Intelligence by making data faster, more flexible and more customized,” said Scott Hilleboe, managing director, H.I.G. Growth Partners, in a statement. “The Mode data platform speeds up answers to complex business problems and makes the process more collaborative, so that everyone can build on the work of data analysts. We believe the company’s innovations in data analytics uniquely position it to take the lead in the Decision Science marketplace.”

Steer said that fundraising was planned long before the coronavirus outbreak to start in February, which meant that it was timed as badly as it could have been. Mode still raised what it wanted to in a couple of months — “a good raise by any standard,” he noted — even if it’s likely that the valuation suffered a bit in the process. “Pitching while the stock market is tanking was terrifying and not something I would repeat,” he added.

Given how many acquisitions there have been in this space, Steer confirmed that Mode too has been approached a number of times, but it’s staying put for now. (And no, he wouldn’t tell me who has been knocking, except to say that it’s large companies for whom analytics is an “adjacency” to bigger businesses, which is to say, the very large tech companies have approached Mode.)

“The reason we haven’t considered any acquisition offers is because there is just so much room,” Steer said. “I feel like this market is just getting started, and I would only consider an exit if I felt like we were handicapped by being on our own. But I think we have a lot more growing to do.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Special is a new startup offering online video creators a way to move beyond advertising for their income.

The service was created by the team behind tech consulting and development firm Triple Tree Software. Special’s co-founder and CEO Sam Lucas told me that the team had already “scrapped our way from nothing to a seven-figure annual revenue,” but when the founders met with Next Frontier Capital (Next Frontier, like Special, is based in Bozeman, Montana) they pitched a bigger idea — an app where creators charge a subscription fee for access to premium content.

While Triple Tree started in the service business, Lucas explained the goal was always to create “a product company that we could sell for $100 million.” Now Special is announcing it has raised $2.26 million in seed funding from Next Frontier and other investors.

It’s also built an initial version of the product that’s being tested by friends, family and a handful of creators, with plans for a broader beta release in October.

With online advertising slowing dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic, YouTube recently highlighted the fact that 80,000 of its channels are earning money from non-ad sources, and that the number of creators who receive the majority of their income from those sources grew 40% between January and May.

One of the main ways that creators can ask their viewers for money is through Patreon. Lucas acknowledged Patreon as a “very big inspiration” for Special, but he said that conversations with creators pointed to a few key ways that the service falls short.

Image Credits: Special

For one thing, he argued while contributions on Patreon are framed as “donations” or “support,” Special allows creators to emphasize the value of their premium content by putting it behind a subscription paywall. Patreon supports paywalls as well, but that leads to Lucas’ next point — it was built for creators of all kinds, while Special is focused specifically on video, and it has built a high-quality video player into the experience.

In fact, Lucas described Special’s spin on the idea of a white-labeled product as “silver label.” The goal is to create “the perfect balance between a platform and a custom app” — creators get their own customizable channels that emphasize their brand identity (rather than Special’s), while still getting the distribution and exposure benefits of being part of a larger platform, with their content searchable and viewable on web, mobile and smart TVs.

Creators also retain ownership of their content, and they get to decide how much they want to charge subscribers — Lucas said it can be anywhere between “$1 or $999” per month, with Special taking a 10% fee. He added that the team has plans to build a bundling option that would allow creators to team up and offer a joint subscription.

Lucas’ pitch reminded me of startups like Vessel (acquired and shut down by TechCrunch’s parent company Verizon in 2016), which previously hoped to bring online creators together for a subscription offering. In Lucas’ view, Vessel was similar to newer apps like Quibi, in that they directly funded creators to produce exclusive content.

“It’s a billion-dollar arms race, with what used to be a technology play but is now a production studio play,” he said. Special doesn’t have the funding to compete at that level, but Lucas suggested that a studio model also provides the wrong incentives to creators, who say “Hell yeah, keep those checks coming in,” but disappear “the moment the checks stop.”

“I almost think it’s an egotistical play,” Lucas added. “The company thinks they know best what a creator should produce for an audience that doesn’t exist yet. We say: Let them do it on Special. Do whatever you want, as long as you follow our terms of service, and own your creative vision.”

It might also seem like a big challenge to recruit creators while based in Montana, but Lucas replied that Special has more access than you might think, especially since the town has become “such a hotspot for extremely wealthy people to buy their third home.”

More broadly, he suggested that the distance from Hollywood and Silicon Valley “allows us to not follow the trends of every new streaming platform and [instead] truly find those independent creators underneath the woodworks.”

Powered by WPeMatico

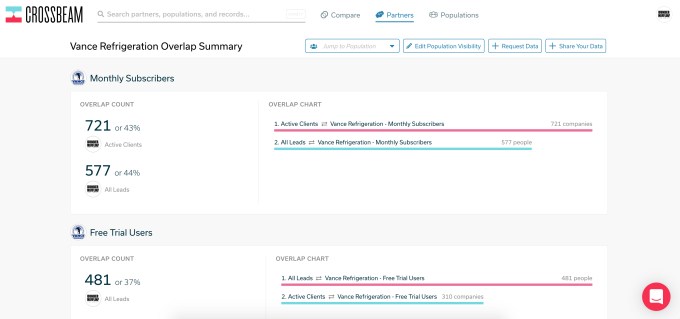

As sales teams partner with other companies, they go through a process called account mapping to find common customers and prospects. This is usually a highly manual activity tracked in spreadsheets. Crossbeam, a Philadelphia startup, has come up with a way to automate partnership data integration. Today the company announced a $25 million Series B investment.

Redpoint Ventures led the round with help from existing investors FirstMark Capital, Salesforce Ventures, Slack Fund and Uncork Capital, along with new investors Okta Ventures and Partnership Leaders, a partnership industry association. All in all, an interesting mix of traditional VCs and strategic investors that Crossbeam could potentially partner with as they grow the business.

The funding comes on the heels of a $3.5 million seed round in 2018 and a $12.5 million Series A a year ago. The startup has now raised a total of $41 million.

Crossbeam has been growing steadily, and that attracted the attention of investors, whom CEO and co-founder Bob Moore says approached him. He was actually not thinking about fundraising until next year, but when the opportunity presented itself, he decided to seize it.

The platform has a natural networking effect built into it with over 900 companies using it so far. As new companies come on, they invite partners, who can join and invite more partners, and that creates a constant sales motion for them without much effort at all.

“We didn’t go out fundraising. We caught the eye of Redpoint because they could see the virality of the product and the extent to which it was being used by many of their portfolio companies and companies out in the market […],” Moore told TechCrunch.

Image Credits: Crossbeam

To accelerate interest in the product, the company also announced a new free tier, which replaces the limited free trial and a starter level that previously cost $500 per month. Prior to this move, if you didn’t move to the starter tier, you would lose your data when the trial was over.

“The idea here is what we’ve seen in the data is that we can create a whole lot of value for people and demonstrate really strong ROI once they get in the door and actually have access to that data, and they don’t have to worry about a free trial where the data is going away,” Moore explained.

Moore says they currently have 28 employees and have ambitious plans to add new people to the mix in the coming months, expecting to reach 50 employees by early 2021. As the company revs up on the personnel side, Moore says diversity is front and center of their plans.

“As far as Crossbeam specifically goes, we’ve made sure that diversity, equity and inclusion is part of our entire recruiting process and also the cultural experience that we create for people that are at the company,” he said. Although he didn’t discuss specific numbers, he said the company was making progress, particularly in the latest round of hires.

While the company has an office in Philly, even before COVID hit, it was a remote first organization with about half of the employees working from home. “I think a lot of our culture was kind of built to make sure that remote team members are first-class citizens in every respect in the company. So we already had all the controls, technology and practices in place, and when we shut the office, it was about as smooth as could be,” he said.

Powered by WPeMatico

Krisp’s smart noise suppression tech, which silences ambient sounds and isolates your voice for calls, arrived just in time. The company got out in front of the global shift to virtual presence, turning early niche traction into real customers and attracting a shiny new $5 million Series A funding round to expand and diversify its timely offering.

We first met Krisp back in 2018 when it emerged from UC Berkeley’s Skydeck accelerator. The company was an early one in the big surge of AI startups, but with a straightforward use case and obviously effective tech it was hard to be skeptical about.

Krisp applies a machine learning system to audio in real time that has been trained on what is and isn’t the human voice. What isn’t a voice gets carefully removed even during speech, and what remains sounds clearer. That’s pretty much it! There’s very little latency (15 milliseconds is the claim) and a modest computational overhead, meaning it can work on practically any device, especially ones with AI acceleration units like most modern smartphones.

The company began by offering its standalone software for free, with a paid tier that removed time limits. It also shipped integrated into popular social chat app Discord. But the real business is, unsurprisingly, in enterprise.

“Early on our revenue was all pro, but in December we started onboarding enterprises. COVID has really accelerated that plan,” explained Davit Baghdasaryan, co-founder and CEO of Krisp. “In March, our biggest customer was a large tech company with 2,000 employees — and they bought 2,000 licenses, because everyone is remote. Gradually enterprise is taking over, because we’re signing up banks, call centers and so on. But we think Krisp will still be consumer-first, because everyone needs that, right?”

Now even more large companies have signed on, including one call center with some 40,000 employees. Baghdasaryan says the company went from 0 to 600 paying enterprises, and $0 to $4 million annual recurring revenue, in a single year, which probably makes the investment — by Storm Ventures, Sierra Ventures, TechNexus and Hive Ventures — look like a pretty safe one.

It’s a big win for the Krisp team, which is split between the U.S. and Armenia, where the company was founded, and a validation of a global approach to staffing — world-class talent isn’t just to be found in California, New York, Berlin and other tech centers, but in smaller countries that don’t have the benefit of local hype and investment infrastructure.

Funding is another story, of course, but having raised money the company is now working to expand its products and team. Krisp’s next move is essentially to monitor and present the metadata of conversation.

“The next iteration will tell you not just about noise, but give you real time feedback on how you are performing as a speaker,” Baghdasaryan explained. Not in the toastmasters sense, exactly, but haven’t you ever wondered about how much you actually spoke during some call, or whether you interrupted or were interrupted by others, and so on?

“Speaking is a skill that people can improve. Think Grammar.ly for voice and video,” Baghdasaryan ventured. “It’s going to be subtle about how it gives that feedback to you. When someone is speaking they may not necessarily want to see that. But over time we’ll analyze what you say, give you hints about vocabulary, how to improve your speaking abilities.”

Since architecturally Krisp is privy to all audio going in and out, it can fairly easily collect this data. But don’t worry — like the company’s other products, this will be entirely private and on-device. No cloud required.

“We’re very opinionated here: Ours is a company that never sends data to its servers,” said Baghdasaryan. “We’re never exposed to it. We take extra steps to create and optimize our tech so the audio never leaves the device.”

That should be reassuring for privacy wonks who are suspicious of sending all their conversations through a third party to be analyzed. But after all, the type of advice Krisp is considering can be done without really “understanding” what is said, which also limits its scope. It won’t be coaching you into a modern Cicero, but it might help you speak more consistently or let you know when you’re taking up too much time.

For the immediate future, though, Krisp is still focused on improving its noise-suppression software, which you can download for free here.

Powered by WPeMatico

When Rent the Runway co-founders Jennifer Fleiss and Jennifer Hyman got their first term sheet, it had an exploding clause in it: If they didn’t sign the offer in 24 hours, they would lose the deal.

The co-founders, then students at Harvard Business School, were ready to commit, but their lawyer advised them to pause and attend the meetings they had previously set up with other investors.

Twelve years later, Rent the Runway has raised $380 million in venture capital equity funding from top investors like Alibaba’s Jack Ma, Temasek, Fidelity, Highland Capital Partners and T. Rowe Capital. Fleiss gave up an operational role in the company to a board seat in 2017, as the company reportedly was eyeing an IPO.

But the shoe didn’t always fit: Earlier this year, Rent the Runway struggled with supply chain issues that left customers disgruntled. Then, the pandemic threatened the market of luxury wear more broadly: Who needs a ball gown while Zooming from home? In early March, the business went through a restructuring, furloughing and laying off nearly half of its workforce, including every retail employee at its physical locations.

In 2009, Fleiss and Hyman were successful Harvard Business School students. Hyman’s college roommate knew a prominent lawyer who agreed to advise them on a contingency basis in exchange for connecting them with potential investors.

Still, fundraising “was extremely hard,” Hyman said. “We were in the middle of a recession and we were two young women at business school who had never really done anything before.”

Fleiss said venture capital firms often sent junior associates, receptionists and assistants to take the meeting instead of dispatching a full-time partner. “It was clear they weren’t taking us very seriously,” Fleiss said, recounting that on one occasion, a male investor called his wife and daughter on speaker to vet their thoughts.

In an attempt to test their thesis that women would pay to rent (and return) luxury clothing, Fleiss and Hyman started doing trunk pop-up shows with 100 dresses. On one occasion, they rented out a Harvard undergraduate dorm room common hall and invited sororities, student activity organizations and a handful of investors.

Only one person showed up, said Fleiss: A guy “who was 30 years older than anyone else in the room.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Software valuations are bonkers, which means it’s a great time to go public. Asana, Monday.com, Wrike and every other gosh darn software company that is putting it off, pay attention. Heck, even service-y Palantir could excel in this market.

Let me explain.

Over the past few weeks, TechCrunch has tracked the filing, first pricing, rejiggered pricing range, and, today, the first day of trading for BigCommerce, a Texas-based e-commerce company. You can think of it as a comp with Shopify to a degree.

Image Credits: IMGFlip (opens in a new window)

In the wake of the Canadian phenom’s blockbuster earnings report, BigCommerce boosted its IPO range. Yesterday the company did itself one better, pricing $1 per share above that raised range, selling 9,019,565 shares at $24 per share, of which 6,850,000 came from BigCommerce itself.

Before some additions, there are now 65,843,546 shares of BigCommerce in the world, giving the company an IPO valuation of around $1.58 billion.

Given that the company’s Q2 expected revenue range is “between $35.5 million and $35.8 million,” the company sported a run-rate multiple of 11.1x to 11x, depending on where its final revenue tally comes in. That felt somewhat reasonable, if perhaps a smidgen light.

Then the company opened at $68 per share today, currently trading for $82 per share. Hello, 1999 and other insane times. BigCommerce is now worth, using some rough math, around $5.4 billion, giving it a run-rate multiple of around 38x, using the midpoint of its Q2 revenue range.

Powered by WPeMatico

While a handful of tech companies like Zoom and Shopify are enjoying massive gains as a result of COVID-19, that’s obviously not the case for most. Weaker demand, slower sales cycles, and customer insistence on pricing concessions and payment deferrals have conspired to cloud the outlook for many tech companies’ growth.

Compounding these challenges, a lot of tech companies are struggling to raise capital just when they need it most. The data so far suggests that investors, particularly those focused on earlier stage financings, are taking a more cautious approach to new deals and valuations while they wait to see how individual companies perform and which way the economy will go. With the outcome of their planned equity financings uncertain, some tech companies are revisiting their funding strategies and exploring alternative sources of capital to fuel their continued growth.

For certain businesses, COVID-19’s impact on revenue was immediate. For others, the effects of slower economic activity and tighter budgets surfaced more gradually with deals in the funnel before the pandemic closing in April and May. Either way, in the second half of 2020, technology CFOs face a common challenge: How do you accurately forecast sales when there’s very little consensus around key issues such as when business activity will return to pre-COVID levels and what the long-term effects of the crisis might be?

Unfortunately, navigating this uncertainty is just as daunting a challenge for investors. These days, equity investors’ assessment of a company’s growth potential, and the value they are willing to pay for that growth, aren’t just impacted by their view of the company itself. Equally important is their assumptions about when the economy will recover and what the new normal might look like. This uncertainty can lead to situations where companies and their potential investors have materially different views on valuation.

While the full impact of COVID was felt too late to have a material impact on Q1 deal volumes, recently released data from Pitchbook and the NVCA suggest that 2020 will see a significant decrease in the number of companies funded, possibly by as much 30 percent compared to 2019 among early stage companies. And, while it often takes several months to see evidence of broad trends in investment terms, anecdotal evidence indicates investors are seeking to mitigate risk by demanding additional protective provisions.

Powered by WPeMatico

It takes a village — or in this case a kickass global startup community — to help you survive and thrive in challenging times. Tap into your village at Disrupt 2020, but do it quickly to gain entry at the lowest possible price. You have just three days left before the price goes up.

Buy an early-bird pass to Disrupt before August 7 at 11:59 p.m. (PDT), and you can save up to $300.

The virtual Disrupt 2020 programming runs from September 14-18, but you can start networking weeks ahead of time with CrunchMatch. Answer a few quick questions and our enhanced AI-powered platform finds and connects you with people who can help you achieve your business goals. CrunchMatch makes fast, precise matches and gets smarter the more you use it, so go nuts — schedule 1:1 video meetings with potential investors, customers, or founders, showcase your innovative products or interview prospective employees.

We’re dedicated to supporting early-stage founders and, to that end, we’ve created a new series of sessions we call The Pitch Deck Teardown. We invite Disrupt attendees to submit their pitch decks (we’ll give preference to early-stage startups) for a slide-by-slide analysis by top venture capitalists.

They’ll talk about what does and doesn’t work in your deck and suggest changes to make it stronger and more compelling. You’ll learn what VCs look for and what they consider red flags that can derail your dream. We’re planning multiple sessions throughout Disrupt, and if you want to be considered for a tear down, submit your pitch deck here.

There’s so much opportunity waiting for you at Disrupt. Explore hundreds of innovative startups, including the TC Top Picks, in Digital Startup Alley, see who takes home $100,000 in the Startup Battlefield pitch competition and don’t miss the top tech, investment and business minds sharing their insight and experience across the Disrupt stages.

Join your village to learn new ways to survive and thrive. It starts by saving up to $300, but that deal disappears in three days. Buy your pass to Disrupt before early-bird pricing ends on August 7 at 11:59 p.m. (PDT).

Is your company interested in sponsoring or exhibiting at Disrupt 2020? Contact our sponsorship sales team by filling out this form.

Powered by WPeMatico

America’s technology industry, radiating brilliance and profitability from its Silicon Valley home base, was until recently a shining beacon of what made America great: Science, progress, entrepreneurship. But public opinion has swung against big tech amazingly fast and far; negative views doubled between 2015 and 2019 from 17% to 34%. The list of concerns is long and includes privacy, treatment of workers, marketplace fairness, the carnage among ad-supported publications and the poisoning of public discourse.

But there’s one big issue behind all of these: An industry ravenous for growth, profit and power, that has failed at treating its employees, its customers and the inhabitants of society at large as human beings. Bear in mind that products, companies and ecosystems are built by people, for people. They reflect the values of the society around them, and right now, America’s values are in a troubled state.

We both have a lot of respect and affection for the United States, birthplace of the microprocessor and the electric guitar. We could have pursued our tech careers there, but we’ve declined repeated invitations and chosen to stay at home here in Canada . If you want to build technology to be harnessed for equity, diversity and social advancement of the many, rather than freedom and inclusion for the few, we think Canada is a good place to do it.

U.S. big tech is correctly seen as having too much money, too much power and too little accountability. Those at the top clearly see the best effects of their innovations, but rarely the social costs. They make great things — but they also disrupt lives, invade privacy and abuse their platforms.

We both came of age at a time when tech aspired to something better, and so did some of today’s tech giants. Four big tech CEOs recently testified in front of Congress. They were grilled about alleged antitrust abuses, although many of us watching were thinking about other ills associated with some of these companies: tax avoidance, privacy breaches, data mining, surveillance, censorship, the spread of false news, toxic byproducts, disregard for employee welfare.

But the industry’s problem isn’t really the products themselves — or the people who build them. Tech workers tend to be dramatically more progressive than the companies they work for, as Facebook staff showed in their recent walkout over President Donald Trump’s posts.

Big tech’s problem is that it amplifies the issues Americans are struggling with more broadly. That includes economic polarization, which is echoed in big-tech financial statements, and the race politics that prevent tech (among other industries) from being more inclusive to minorities and talented immigrants.

We’re particularly struck by the Trump administration’s recent moves to deny opportunities to H-1B visa holders. Coming after several years of family separations, visa bans and anti-immigrant rhetoric, it seems almost calculated to send IT experts, engineers, programmers, researchers, doctors, entrepreneurs and future leaders from around the world — the kind of talented newcomers who built America’s current prosperity — fleeing to more receptive shores.

One of those shores is Canada’s; that’s where we live and work. Our country has long courted immigration, but it’s turned around its longstanding brain-drain problem in recent years with policies designed to scoop up talented people who feel uncomfortable or unwanted in America. We have an immigration program, the Global Talent Stream, that helps innovative companies fast-track foreign workers with specialized skills. Cities like Toronto, Montreal, Waterloo and Vancouver have been leading North America in tech job creation during the Trump years, fuelled by outposts of the big international tech companies but also by scaled-up domestic firms that do things the Canadian way, such as enterprise software developer OpenText (one of us is a co-founder) and e-commerce giant Shopify.

“Canada is awesome. Give it a try,” Shopify CEO Tobi Lütke told disaffected U.S. tech workers on Twitter recently.

But it’s not just about policy; it’s about underlying values. Canada is exceptionally comfortable with diversity, in theory (as expressed in immigration policy) and practice (just walk down a street in Vancouver or Toronto). We’re not perfect, but we have been competently led and reasonably successful in recognizing the issues we need to deal with. And our social contract is more cooperative and inclusive.

Yes, that means public health care with no copays, but it also means more emphasis on sustainability, corporate responsibility and a more collaborative strain of capitalism. Our federal and provincial governments have mostly been applauded for their gusher of stimulative wage subsidies and grants meant to sustain small businesses and tech talent during the pandemic, whereas Washington’s response now appears to have been formulated in part to funnel public money to elites.

American big tech today feels morally adrift, which leads to losing out on talented people who want to live the values Silicon Valley used to stand for — not just wealth, freedom and the few, but inclusivity, diversity and the many. Canada is just one alternative to the U.S. model, but it’s the alternative we know best and the one just across the border, with loads of technology job openings.

It wouldn’t surprise us if more tech refugees find themselves voting with their feet.

Powered by WPeMatico

How and when should startup founders think about the “exit”? It’s the perennial question in tech entrepreneurialism, but the hows and whens are questions to which there are a multitude of answers. For one thing, new founders often forget that the terms of the exit may not eventually be entirely in their control. There’s the board to think of, the strategic direction of the company, the first-in investors, the last-in. You name it. We’ll be chatting about this at Disrupt 2020.

Exits normally happen in only one of two ways: Either the startup gets acquired for enough money to give the investors a return or it grows big enough to list on the public markets. And it just so happens we have two perfect founders who will be able to unpack their own journeys on those two roads.

When Cloudflare went public last year it certainly wasn’t the end of its 10-year journey, and nor was it PlanGrid’s when it was acquired by Autodesk in 2018.

Cloudflare’s Michelle Zatlyn saw every nook and cranny of the company’s journey toward its IPO, which received a warm reception, even if there were a few bumps along the road leading up to it. What comes after an IPO and how do you even get there in the first place? Zatlyn will be laying it all out for us.

PlanGrid’s journey to acquisition by Autodesk was equally fascinating, and Tracy Young — who, as CEO and co-founder, shepherded the company to an $875 million exit — will be able to give us insight into what it’s like to dance with a potential acquirer, go through that (often fraught) process and come out the other side.

We’re excited to host this conversation at Disrupt 2020 and expect it to fill up quickly. Grab your pass before this Friday to save up to $300 on this session and more.

Powered by WPeMatico