real estate

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Juniper Square, a four-year-old startup at the intersection of enterprise software, real estate and financial technology, has brought in an additional $25 million in Series B funding to fuel the growth of its commercial real estate investment platform. Ribbit Capital led the round, with participation from Felicis Ventures.

Founded in 2014 by Alex Robinson, Yonas Fisseha and Adam Ginsburg, the startup’s chief executive officer, vice president of engineering and VP of product, respectively, Juniper has raised a total of $33 million to date.

The company operates a software platform for commercial real estate investment firms — an industry that has been slower to adopt the latest and greatest technology. Robinson tells TechCrunch those firms raise money from pension funds, endowments and elsewhere to purchase and then manage commercial real estate, using Juniper’s software as a tool throughout that process. Juniper supports fundraising and capital management with a suite of customer relationship management (CRM) and productivity tools for its users.

The San Francisco-based company says it currently has hundreds of customers and manages half a trillion dollars in real estate.

“The private markets are just as big as the public markets … but the private markets have typically not been accessible to everyday investors, and that’s part of what we are trying to do with Juniper Square,” Robinson told TechCrunch. “It’s a tremendously large market that almost nobody knows anything about.”

Juniper will use its latest investment to double headcount from 60 to 120 in the year ahead, with plans to beef up its engineering, product and sales teams specifically as the company expects to continue experiencing massive growth. Robinson said it’s grown between 3x and 4x every year for the last three years.

Felicis Ventures managing director Sundeep Peechu said in a statement that Juniper “is one of the fastest growing real estate tech companies” the firm has ever seen: “They are building technology for an industry that touches nearly every human and every corner of the economy. It’s a hard problem that takes time to solve, but the benefits of making these huge markets work better are tremendous.”

Existing in a relatively niche intersection, Juniper’s job now is to prove itself more efficient and user-friendly than Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, which, Robinson says, are still its biggest competitor.

“Our goal is to be the de facto platform for real estate investment and we are well on our way to becoming that.”

Powered by WPeMatico

When the hell did building a house become so complicated?

Don’t let the folks on HGTV fool you. The process of building a home nowadays is incredibly painful. Just applying for the necessary permits can be a soul-crushing undertaking that’ll have you running around the city, filling out useless forms, and waiting in motionless lines under fluorescent lights at City Hall wondering whether you should have just moved back in with your parents.

Consider this an ongoing discussion about Urban Tech, its intersection with regulation, issues of public service, and other complexities that people have full PHDs on. I’m just a bitter, born-and-bred New Yorker trying to figure out why I’ve been stuck in between subway stops for the last 15 minutes, so please reach out with your take on any of these thoughts: @Arman.Tabatabai@techcrunch.com.

And to actually get approval for those permits, your future home will have to satisfy a set of conditions that is a factorial of complex and conflicting federal, state and city building codes, separate sets of fire and energy requirements, and quasi-legal construction standards set by various independent agencies.

It wasn’t always this hard – remember when you’d hear people say “my grandparents built this house with their bare hands?” These proliferating rules have been among the main causes of the rapidly rising cost of housing in America and other developed nations. The good news is that a new generation of startups is identifying and simplifying these thickets of rules, and the future of housing may be determined as much by machine learning as woodworking.

Photo by Bill Oxford via Getty Images

Cities once solely created the building codes that dictate the requirements for almost every aspect of a building’s design, and they structured those guidelines based on local terrain, climates and risks. Over time, townships, states, federally-recognized organizations and independent groups that sprouted from the insurance industry further created their own “model” building codes.

The complexity starts here. The federal codes and independent agency standards are optional for states, who have their own codes which are optional for cities, who have their own codes that are often inconsistent with the state’s and are optional for individual townships. Thus, local building codes are these ever-changing and constantly-swelling mutant books made up of whichever aspects of these different codes local governments choose to mix together. For instance, New York City’s building code is made up of five sections, 76 chapters and 35 appendices, alongside a separate set of 67 updates (The 2014 edition is available as a book for $155, and it makes a great gift for someone you never want to talk to again).

In short: what a shit show.

Because of the hyper-localized and overlapping nature of building codes, a home in one location can be subject to a completely different set of requirements than one elsewhere. So it’s really freaking difficult to even understand what you’re allowed to build, the conditions you need to satisfy, and how to best meet those conditions.

There are certain levels of complexity in housing codes that are hard to avoid. The structural integrity of a home is dependent on everything from walls to erosion and wind-flow. There are countless types of material and technology used in buildings, all of which are constantly evolving.

Thus, each thousand-page codebook from the various federal, state, city, township and independent agencies – all dictating interconnecting, location and structure-dependent needs – lead to an incredibly expansive decision tree that requires an endless set of simulations to fully understand all the options you have to reach compliance, and their respective cost-effectiveness and efficiency.

So homebuilders are often forced to turn to costly consultants or settle on designs that satisfy code but aren’t cost-efficient. And if construction issues cause you to fall short of the outcomes you expected, you could face hefty fines, delays or gigantic cost overruns from redesigns and rebuilds. All these costs flow through the lifecycle of a building, ultimately impacting affordability and access for homeowners and renters.

Photo by Caiaimage/Rafal Rodzoch via Getty Images

Strap on your hard hat – there may be hope for your dream home after all.

The friction, inefficiencies, and pure agony caused by our increasingly convoluted building codes have given rise to a growing set of companies that are helping people make sense of the home-building process by incorporating regulations directly into their software.

Using machine learning, their platforms run advanced scenario-analysis around interweaving building codes and inter-dependent structural variables, allowing users to create compliant designs and regulatory-informed decisions without having to ever encounter the regulations themselves.

For example, the prefab housing startup Cover is helping people figure out what kind of backyard homes they can design and build on their properties based on local zoning and permitting regulations.

Some startups are trying to provide similar services to developers of larger scale buildings as well. Just this past week, I covered the seed round for a startup called Cove.Tool, which analyzes local building energy codes – based on location and project-level characteristics specified by the developer – and spits out the most cost-effective and energy-efficient resource mix that can be built to hit local energy requirements.

And startups aren’t just simplifying the regulatory pains of the housing process through building codes. Envelope is helping developers make sense of our equally tortuous zoning codes, while Cover and companies like Camino are helping steer home and business-owners through arduous and analog permitting processes.

Look, I’m not saying codes are bad. In fact, I think building codes are good and necessary – no one wants to live in a home that might cave in on itself the next time it snows. But I still can’t help but ask myself why the hell does it take AI to figure out how to build a house? Why do we have building codes that take a supercomputer to figure out?

Ultimately, it would probably help to have more standardized building codes that we actually clean-up from time-to-time. More regional standardization would greatly reduce the number of conditional branches that exist. And if there was one set of accepted overarching codes that could still set precise requirements for all components of a building, there would still only be one path of regulations to follow, greatly reducing the knowledge and analysis necessary to efficiently build a home.

But housing’s inherent ties to geography make standardization unlikely. Each region has different land conditions, climates, priorities and political motivations that cause governments to want their own set of rules.

Instead, governments seem to be fine with sidestepping the issues caused by hyper-regional building codes and leaving it up to startups to help people wade through the ridiculousness that paves the home-building process, in the same way Concur aids employee with infuriating corporate expensing policies.

For now, we can count on startups that are unlocking value and making housing more accessible, simpler and cheaper just by making the rules easier to understand. And maybe one day my grandkids can tell their friends how their grandpa built his house with his own supercomputer.

Powered by WPeMatico

As the fight against climate change heats up, Cove.Tool is looking to help tackle carbon emissions one building at a time.

The Atlanta-based startup provides an automated big-data platform that helps architects, engineers and contractors identify the most cost-effective ways to make buildings compliant with energy efficiency requirements. After raising an initial round earlier this year, the company completed the final close of a $750,000 seed round. Since the initial announcement of the round earlier this month, Urban Us, the early-stage fund focused on companies transforming city life, has joined the syndicate comprised of Tech Square Labs and Knoll Ventures.

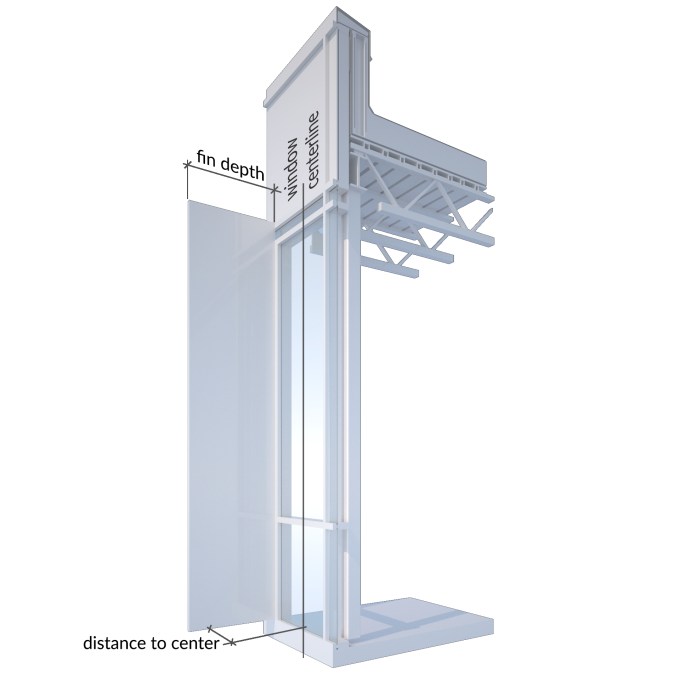

Cove.Tool software allows building designers and managers to plug in a variety of building conditions, energy options, and zoning specifications to get to the most cost-effective method of hitting building energy efficiency requirements (Cove.Tool Press Image / Cove.Tool / https://covetool.com).

In the US, the buildings we live and work in contribute more carbon emissions than any other sector. Governments across the country are now looking to improve energy consumption habits by implementing new building codes that set higher energy efficiency requirements for buildings.

However, figuring out the best ways to meet changing energy standards has become an increasingly difficult task for designers. For one, buildings are subject to differing federal, state and city codes that are all frequently updated and overlaid on one another. Therefore, the specific efficiency requirements for a building can be hard to understand, geographically unique and immensely variable from project to project.

Architects, engineers and contractors also have more options for managing energy consumption than ever before – equipped with tools like connected devices, real-time energy-management software and more-affordable renewable energy resources. And the effectiveness and cost of each resource are also impacted by variables distinct to each project and each location, such as local conditions, resource placement, and factors as specific as the amount of shade a building sees.

With designers and contractors facing countless resource combinations and weightings, Cove.Tool looks to make it easier to identify and implement the most cost-effective and efficient resource bundles that can be used to hit a building’s energy efficiency requirements.

Cove.Tool users begin by specifying a variety of project-specific inputs, which can include a vast amount of extremely granular detail around a building’s use, location, dimensions or otherwise. The software runs the inputs through a set of parametric energy models before spitting out the optimal resource combination under the set parameters.

For example, if a project is located on a site with heavy wind flow in a cold city, the platform might tell you to increase window size and spend on energy efficient wall installations, while reducing spending on HVAC systems. Along with its recommendations, Cove.Tool provides in-depth but fairly easy-to-understand graphical analyses that illustrate various aspects of a building’s energy performance under different scenarios and sensitivities.

Cove.Tool users can input granular project-specifics, such as shading from particular beams and facades, to get precise analyses around a building’s energy performance under different scenarios and sensitivities.

Traditionally, the design process for a building’s energy system can be quite painful for architecture and engineering firms.

An architect would send initial building designs to engineers, who then test out a variety of energy system scenarios over the course a few weeks. By the time the engineers are able to come back with an analysis, the architects have often made significant design changes, which then gets sent back to the engineers, forcing the energy plan to constantly be 1-to-3 months behind the rest of the building. This process can not only lead to less-efficient and more-expensive energy infrastructure, but the hectic back-and-forth can lead to longer project timelines, unexpected construction issues, delays and budget overruns.

Cove.Tool effectively looks to automate the process of “energy modeling.” The energy modeling looks to ease the pains of energy design in the same ways Building Information Modeling (BIM) has transformed architectural design and construction. Just as BIM creates predictive digital simulations that test all the design attributes of a project, energy modeling uses building specs, environmental conditions, and various other parameters to simulate a building’s energy efficiency, costs and footprint.

By using energy modeling, developers can optimize the design of the building’s energy system, adjust plans in real-time, and more effectively manage the construction of a building’s energy infrastructure. However, the expertise needed for energy modeling falls outside the comfort zones of many firms, who often have to outsource the task to expensive consultants.

The frustrations of energy system design and the complexities of energy modeling are ones the Cove.Tool team knows well. Patrick Chopson and Sandeep Ajuha, two of the company’s three co-founders, are former architects that worked as energy modeling consultants when they first began building out the Cove.Tool software.

After seeing their clients’ initial excitement over the ability to quickly analyze millions of combinations and instantly identify the ones that produce cost and energy savings, Patrick and Sandeep teamed up with CTO Daniel Chopson and focused full-time on building out a comprehensive automated solution that would allow firms to run energy modeling analysis without costly consultants, more quickly, and through an interface that would be easy enough for an architectural intern to use.

So far there seems to be serious demand for the product, with the company already boasting an impressive roster of customers that includes several of the country’s largest architecture firms, such as HGA, HKS and Cooper Carry. And the platform has delivered compelling results – for example, one residential developer was able to identify energy solutions that cost $2 million less than the building’s original model. With the funds from its seed round, Cove.Tool plans further enhance its sales effort while continuing to develop additional features for the platform.

The value proposition Cove.Tool hopes to offer is clear – the company wants to make it easier, faster and cheaper for firms to use innovative design processes that help identify the most cost-effective and energy-efficient solutions for their buildings, all while reducing the risks of redesign, delay and budget overruns.

Longer-term, the company hopes that it can help the building industry move towards more innovative project processes and more informed decision-making while making a serious dent in the fight against emissions.

“We want to change the way decisions are made. We want decisions to move away from being just intuition to become more data-driven.” The co-founders told TechCrunch.

“Ultimately we want to help stop climate change one building at a time. Stopping climate change is such a huge undertaking but if we can change the behavior of buildings it can be a bit easier. Architects and engineers are working hard but they need help and we need to change.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Today, Real Estate Technology Ventures (RET Ventures) announced the final close of $108 million for its first fund. RET focuses on early-stage investments in companies that are primarily looking to disrupt the North American multifamily rental industry, with the firm boasting a roster of LPs made up of some of the largest property owners and operators in the multifamily space.

RET is one of the latest in a rising number of venture firms focused on the real estate sector, which by many accounts has yet to experience significant innovation or technological disruption.

The firm was founded in 2017 by managing director John Helm, who possesses an extensive background as an operator and investor in both real estate and real estate technology. Helm’s real estate journey began with a position right out of college and eventually led him to the commercial brokerage giant Marcus & Millichap, where he worked as CFO before leaving to build two venture-backed real estate technology companies. After successfully selling both companies, Helm worked as a venture partner at Germany-based DN Capital, where he invested in companies such as PurpleBricks and Auto1.

Speaking with investors and past customers, John realized there was a need for a venture fund specifically focused on the multifamily rental sector. RET points out that while multifamily properties have traditionally fallen under the commercial real estate umbrella, operators are forced to deal with a wide set of idiosyncratic dynamics unique to the vertical. In fact, outside of a select group, most of the companies and real estate investment trusts that invest in multifamily tend to invest strictly within the sector.

Now, RET has partnered with leading multifamily owners to help identify innovative startups that can help the LPs better run their portfolios, which account for nearly a million units across the country in aggregate. With its deep sector expertise and its impressive LP list, RET believes it can bring tremendous value to entrepreneurs by providing access to some of the largest property owners in the U.S., effectively shortening a notoriously lengthy sales cycle and making it much easier to scale.

Photo: Alexander Kirch/Shutterstock

One of the first companies reaping the benefits of RET’s deep ties to the real estate industry is SmartRent, the startup providing a property analytics and automation platform for multifamily property managers and renters. Today, SmartRent announced it had closed $5 million in series A financing, with seed investor RET providing the entire round.

SmartRent essentially provides property managers with many of the smart home capabilities that have primarily been offered to consumers to date, making it easier for them to monitor units remotely, avoid costly damages and streamline operations, all while hopefully enhancing the resident experience through all-in-one home controls.

By combining connected devices with its web and mobile platform, SmartRent hopes to provide tools that can help identify leaks or faulty equipment, eliminate energy waste and provide remote access control for door locks. The functions provided by SmartRent are particularly valuable when managing vacant units, in which leaks or unnecessary energy consumption can often go unnoticed, leading to multimillion-dollar damage claims or inflated utility bills. SmartRent also attempts to enhance the leasing process for vacant units by pre-screening potential renters that apply online and allowing qualified applicants to view the unit on their own without a third-party sales agent.

Just like RET, SmartRent is the brainchild of accomplished real estate industry vets. Founder and CEO Lucas Haldeman was still the CTO of Colony Starwood’s single-family portfolio when he first rolled out an early version of the platform in around 26,000 homes. Haldeman quickly realized how powerful the software was for property managers and decided to leave his C-suite position at the publicly traded REIT to found SmartRent.

According to RET, the strong industry pedigree of the founding team was one of the main drivers behind its initial investment in SmartRent and is one of the main differentiators between the company and its competitors.

With RET providing access to its leading multifamily owner LPs, SmartRent has been able to execute on a strong growth trajectory so far, with the company on pace to complete 15,000 installations by the end of the year and an additional 35,000 apartments committed for 2019. And SmartRent seems to have a long runway ahead. The platform can be implemented in any type of rental property, from retrofit homes to high rises, and has only penetrated a small portion of the nearly one million units owned by RET’s LPs alone.

SmartRent has now raised $10 million to date and hopes to use this latest round of funding to ramp growth by broadening its sales and marketing efforts. Longer-term, SmartRent hopes to permeate throughout the entire multifamily industry while continuing to improve and iterate on its platform.

“We’re so early on and we’ve made great progress, but we want to make deep penetration into this industry,” said Haldeman. “There are millions of apartment units and we want to be over 100,000 by year one, and over a million units by year three. At the same time, we’re continuing to enhance our offering and we’re focused on growing and expanding.”

As for RET Ventures, the firm hopes the compelling value proposition of its deep LP and industry network can help RET become the go-to venture firm startups looking to disrupt the real estate rental sector.

Powered by WPeMatico

Earlier this week in a new experimental newsletter I’ve been helping Danny Crichton on, we briefly discussed transit pundit Jarrett Walker’s article in The Atlantic arguing against the view that ridesharing and microtransit will be the future of mass transit. Instead, his thesis is that a properly operated and well-resourced bus system is much more efficient from a coverage, cost, space, and equality perspective.

Consider this an ongoing discussion about Urban Tech, its intersection with regulation, issues of public service, and other complexities that people have full PHDs on. I’m just a bitter, born-and-bred New Yorker trying to figure out why I’ve been stuck in between subway stops for the last 15 minutes, so please reach out with your take on any of these thoughts: @Arman.Tabatabai@techcrunch.com.

From an output perspective, Walker argues that by operating along variable routes based on at-your-door pick ups, microtransit actually takes more time to pick up fewer people on average. Walker also gives buses the edge from a cost and input perspective, since labor makes up 70% of transit operating costs in a pre-autonomous world and buses allow you to service more customers for the price of one driver.

“The driver’s time is far more expensive than maintenance, fuel, and all the other costs involved. In almost every public meeting I attend, citizens complain about seeing buses with empty seats, lecturing me about how smaller vehicles would be less wasteful. But that’s not the case. Because the cost is in the driver, a wise transit agency runs the largest bus it will ever need during the course of a shift. In an outer suburb, that empty big bus makes perfect sense if it will be mobbed by schoolchildren or commuters twice a day.”

But transit is not solely an issue of volume and unit economics, but one of managing public space. Walker explains that to ensure citizens don’t use more than their fair share of space, cities can either provide vehicles that are only marginally bigger than a human body, i.e. bikes and scooters, or have many people share large-scale vehicles, i.e. mass transit. Doing the latter through a mass fleet of on-demand microtransit solutions, Walker argues, increases congestion and makes it harder to manage scheduling and allocate infrastructure.

While the article offers an effective comparison of unit economics and acts as a useful primer on the various considerations for city transit agencies, some of the conclusions are a bit binary. The discussion is a bit singular in its focus of microtransit as a replacement of public transit rather than an additive service and doesn’t give much credit to the trip planning and space management capabilities of many microtransit services, nor changes in consumer expectations towards transportation.

But despite some of the gaps in the piece, Walker highlights two ideas that spill over to some broad areas that have caught my interest lately: Tolls and Parking.

Photo by Michael H via Getty Images

“To succeed, microtransit would have to help people get around cities better, not just make them feel good about hailing a ride on a phone. Full automation of vehicles, if indeed it ever arrives, might solve the labor problem—although it would put thousands of drivers out of work. But the congestion problem will remain.”

Like many, Walker argues that ridesharing aggravates city traffic rather than alleviates it. Even though ridesharing’s long-term impact on traffic is widely contested, nearly everyone agrees that a solution to urban congestion is desperately needed.

What’s interesting is that regardless of the discourse that surrounds them, trends in US tolling mechanisms seem to suggest American cities may be moving closer to congestion pricing methods.

As an example, solutions to congestion are top of mind behind the New York state election that saw Democrats taking control of both state legislative houses. Though it seems like the argument resurfaces every few years, the elections have brought renewed debate over the possible implementation of congestion pricing in New York City. In essence, congestion pricing is a system where drivers would pay higher prices for using high-traffic streets or entering high-traffic zones, allowing cities to better dictate the flow of drivers and reduce congestion.

Outside of the obvious political tension created by effectively implementing a new tax, some lawmakers have pushed back on the effectiveness of a congestion pricing policy, with some arguing that it can aggravate income inequality or that a policy addressing construction and pedestrians, rather than vehicles, would have a bigger impact on traffic.

However, over the past year or so, an increasing number of states have been rolling out highway tolls that are priced dynamically, instead of using traditional fixed-price tolls. The exact drivers behind the toll prices vary, with some cities charging prices based on traffic conditions and others charging varying prices for the use of express and HOV lanes.

Several new technologies and companies have also made it easier for local governments to implement more sophisticated, adjustable toll pricing or congestion fees at a much lower cost. In the past, congestion pricing systems around the world have required physical detection systems that can be extremely costly to implement.

Now, companies like ClearRoad are helping governments use a wide range of connected vehicle technologies to establish and collect road usage pricing from any location without the need for physical infrastructure. Oregon is one geography working with ClearRoad to manage its new opt-in road usage program where the state is able to calculate drivers’ usage of certain roads and their gas consumption, and then reimburse them for gas taxes they’re paying.

So even though people are still screaming at each other in state capitols, it seems like we may be closer to seeing congestion pricing in major cities than we think. And while executing these programs can be difficult and painfully slow (often needing to satisfy city regulations and tax laws forty layers deep), if these smaller-scale programs we’re seeing in the US are actually effective, congestion pricing may be a solution to plug chunky budget gaps, better finance infrastructure projects and replace lost gas tax revenue in an electric vehicle future.

In his piece, Walker goes back to some basic principles of urban design, highlighting that at their core, functioning cities come down to how millions of people share a comparatively tiny amount of space.

Walker explains that city dwellers that travel with cars and solo rideshare trips rather than with large-scale shared transit are effectively taking up more than their fair share of public space. While the argument is made in the context of ridesharing and congestion, the same idea applies to the less-discussed impact mass-transit ridesharing can have on city parking.

At least in the near-term, certain cities have seen ridesharing actually increase vehicle usage rather than reduce it (a claim rideshare companies dispute), resulting in an even wider gap between the supply and demand for available parking spots. And if people are using ridesharing but still choosing to own cars regardless, in an indirect fashion, they are similarly reducing the stock of available parking space by more than their fair share.

And while it makes sense that rideshare vehicles should receive a larger portion of the parking stock, given that it serves more passengers, the use of available parking by these vehicles can and has caused tension with local residents that have to store their cars further away.

There are companies like the mobility-focused data platform, Coord, that are working on tools geared towards helping cities and citizens more effectively allocate and plan parking strategies for the future multi-modal transportation network. And theoretically, ridesharing should reduce the number of vehicles in search of parking in the long-term. But at least for now, the impact on parking congestion is just another unintended consequence that weakens the argument for ridesharing as mass transit.

Powered by WPeMatico

Tiny houses are all the rage, but once you put more than a few people in one you have a problem: Where can you go from there?

Nowhere. Exactly.

What you do is, if you need that extra push over the cliff, you know what you do? Talk to Brian Gaudio. Gaudio is the founder of Module Housing, an incremental-building startup from Pittsburgh. Gaudio, formerly of Walt Disney Imagineering, has an architecture background and saw firsthand the need for incremental housing in his work in Biloxi and Latin America. His idea is simple: create a little house that grows with you over time, allowing a single room to turn into a mansion with a few turns of a wrench.

“We think of the home as a recurring revenue stream — buy a starter home today, purchase additions and upgrades in the future. All our homes are designed to change over time — as a homebuyer’s family grows, income grows or needs change,” he said. “We are capital-light compared to other prefab startups in that we don’t own the manufacturing facilities where our homes are built. We leverage existing network of high-performance prefab manufacturers on the East Coast.”

The service does it all: They offer multiple-room dwellings and work with you to order the modules, find land that lets you add on over time and assemble the houses. Like the Craftsman houses of old, you have a few basic styles, but in this case you can buy a one-bedroom Nook house for $212,000 and then add on over time instead of buying a house with seven rooms and realizing you only needed two.

Additional costs include building a foundation and land preparation. It’s also dead easy to add onto your house when you’re ready, said Gaudio, thanks to work they’ve done in modularizing the houses.

“We have patents pending on a removable roof and wall system that simplifies the addition process when a customer is ready to add on,” he said.

The company has raised $1.2 million so far and they have prototype houses in Pittsburgh. They already have orders and they’ve created a Tesla-like reservation system for the folks who want to try out their product.

“I moved back to Pittsburgh to start Module with the goal of making good design accessible to everyone,” he said. “Affordable housing is one of the most critical issues our country faces today. Module is a vehicle to promote responsible, equitable development in cities. We are reimagining housing to be more sustainable, adaptable and better designed.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Hotels can be pricey, and travelers are often forced to leave their rooms for basic things, like food that doesn’t come from the minibar. Yet Airbnb accommodations, which have become the go-to alternative for travelers, can be highly inconsistent.

Domio, a two-year-old, New York-based outfit, thinks there’s a third way: apartment hotels, or “apart hotels,” as the company is calling them.

The idea is to build a brand that travelers recognize as upscale yet affordable, more tech friendly than boutique hotels and features plenty of square footage, which it expects will appeal to both families as well as companies that send teams of employees to cities and want to do it more economically.

Domio has a host of competitors, if you’ll forgive the pun. Marriott International earlier this year introduced a branded home-sharing business called Tribute Portfolio Homes wherein it says it vets, outfits and maintains to hotel standards homes of its choosing. And Marriott is among a growing number of hotels to recognize that customers who stay in a hotel for a business trip or a family vacation might prefer a multi-bedroom apartment with hotel-like amenities.

Property management companies have been raising funding left and right for the same reason. Among them: Sonder, a four-year-old, San Francisco-based startup offering “spaces built for travel and life” that, according to Crunchbase, has raised $135 million from investors, much of it this year; TurnKey, a six-year-old, Austin, Tex.-based home rental management company that has raised $72 million from investors, including via a Series D round that closed back in March; and Vacasa, a nine-year-old, Portland, Ore.-based vacation rental management company that manages more than 10,000 properties and which just this week closed on $64 million in fresh financing that brings its total funding to $207.5 million.

That’s saying nothing of Airbnb itself, which has begun opening hotel-like branded apartment complexes that lease units to both long-term renters and short-term visitors in partnership with development partner Niido.

Whether Domio can stand out from competitors remains to be seen, but investors are happy to provide it the financing to try. The company is today announcing it has raised $12 million in Series A equity funding led by Tribeca Venture Partners, with participation from SoftBank Capital NY and Loric Ventures. The round comes on the heels of Domio announcing a $50 million joint venture last month with the private equity firm Upper 90 to exclusively fund the leasing and operations of as many as 25 apartment-style hotels for group travelers.

Indeed, Domio thinks one advantage it may have over other home-share companies is that rather than manage the far-flung properties of different owners, it can shave costs and improve the quality of its offerings by entering five- to 10-year leases with developers and then branding, furnishing and operating entire “apart hotel” properties. (It even has partners in China making its furniture.)

As CEO and former real estate banker Jay Roberts told us earlier this week, the plan is to open 25 of these buildings across the U.S. over the next couple of years. The units will average 1,500 square feet and feature two to three bedrooms, and, if all goes as planned, they’ll cost 10 to 25 percent below hotel prices, too.

And if the go-go property management market turns? Roberts insists that Domio can “slow down growth if necessary.” He also notes that “Airbnb was founded out of the recession, supported by people who were interested in saving money. We’re starting to see companies that want to be more cost-effective, too.”

Domio had earlier raised $5 million in equity and convertible debt from angel investors in the real estate industry; altogether it has now amassed funding of $67 million.

Powered by WPeMatico

SoftBank may soon own up to 50 percent of WeWork, a well-funded provider of co-working spaces headquartered in New York, according to a new report from The Wall Street Journal.

SoftBank is reportedly weighing an investment between $15 billion and $20 billion, which would come from its $92 billion Vision Fund, a super-sized venture fund led by Japanese entrepreneur and investor Masayoshi Son.

WeWork declined to comment.

SoftBank already owns some 20 percent of WeWork. The firm invested $4.4 billion in the company in August 2017, $1.4 billion of which was set aside to help WeWork expand in China, Japan and Southeast Asia.

This August, WeWork raised another $1 billion from SoftBank in convertible debt. At the same time, WeWork disclosed financials to a handful of media outlets, sharing that its revenue had doubled to $763.8 million in the first half of 2018 as losses increased to $723 million.

SoftBank, for its part, seems to have a hankering for real estate tech. Not only has it become a key stakeholder in WeWork, but it has deployed significant amounts of capital to Opendoor, Compass, Katerra and others.

Last month, the Vision Fund backed Opendoor, a platform for buying and selling homes, with $400 million. The same day, it led a $400 million round for Compass, valuing the real estate brokerage startup at $4.4 billion. As for Katerra, SoftBank poured $865 million into the construction tech business in January.

WeWork, founded in 2010 by Adam Neumann and Miguel McKelvey, has raised nearly $5 billion in a combination of debt and equity funding to date. It was valued at $20 billion in 2017, though reports earlier this summer estimated its valuation would fall somewhere between $35 billion and $40 billion with additional capital from SoftBank. A $40 billion valuation would make it the second most valuable VC-backed company in the U.S. behind only Uber.

WeWork has more than 268,000 members across 287 locations in 23 countries.

Powered by WPeMatico

Urban-X, the urban-tech startup accelerator backed by BMW MINI and early-stage urban-tech fund Urban.Us, hosted a demo day today for its fourth cohort of companies at its Brooklyn HQ. The seven presenting companies offered solutions to issues plaguing modern cities, including toll-road pricing, energy and construction management, and even the inefficiencies of modern cycling helmets.

In a day that offered an impressive display of entrepreneurial talent, here are a few of the companies that really stood out to us:

In hopes of improving landlord transparency, Rentlogic uses years of city government data to create objective algorithmic letter ratings for apartment buildings. As CEO Yale Fox pointed out, despite city-dwellers spending half our paychecks on rent, urban housing hasn’t seen the same rating systems that we use to guide decisions on where we eat, what car we buy, or what shows we binge. Rentlogic allows apartment hunters to screen buildings before signing a lease and avoid committing to unhealthy conditions or an absentee landlord.

Rentlogic partners with landlords looking to obtain a stamp of quality for potential renters, offering an added inspection feature that allows them to hang a letter rating outside their building. The company’s roster of customers already includes Blackstone and Phipps Houses, the largest for-profit and non-profit landlords in the world, respectively.

What stands out with Rentlogic is its ability to scale. Though currently only in New York City, the same data used in New York presumably exists across all major US markets and Rentlogic has minimized the cost of entering new cities by building out the back-end infrastructure required to ingest and analyze the data. From a demand perspective, as renters defer to Rentlogic for quality assurance and more competitors hang “A” ratings outside their buildings, landlords will face more pressure to maintain the same offering.

The idea hit home for a born-and-bred New Yorker with my own set of landlord horror stories, and the first thing I did when I left was look up my building on Rentlogic.

Most companies wish they had mega-campuses or “motherships” where they could offer employees access to sprawling outdoor working areas. For companies based in urban areas, offering outdoor space can be tough, with many parks often privatized, far from city centers, or void of the amenities needed to be productive.

Campsyte transforms underutilized urban outdoor spaces into productive and fun spaces that customers can book for co-working purposes, corporate off-sites, or events. Similar to WeWork’s approach with buildings, Campsyte takes a parking lot, and adds value by filling it with greenery, furniture, electricity, WiFi, and other services. With its services driving nearly 10x the annual revenue per square foot seen by traditional parking lots, the value proposition for lot owners is convincing.

Given the competition companies are facing when it comes to attracting and retaining talent, providing the same amenities as competitors based outside city centers seems invaluable, with Campsyte boasting an extremely impressive roster of partner companies, including LinkedIn, PayPal, Salesforce, and Airbnb.

As anyone who has driven in a city knows, car crashes or accidents can often be caused by the built environment around you. Yet insurers, who focus on personal characteristics like credit scores when underwriting a policy, lack the measurement tools to assess the risk of someone’s external environment.

Founded by an MIT-trained city planner, ODN builds risk models using machine learning and public data records to help insurers evaluate risk and mitigate accidents. The resulting analytics eases the selection process for insurers, allowing them to drive more sales with less cost and risk. ODN is already partnered up with some of the world’s largest insurers including Zurich, Travelers, and Hanover insurance.

The potential use cases for ODN’s technology go far beyond the massive existing insurance market, with the eventual rollout of autonomous cars forcing insurers to ask how they construct policies when human behavior plays no role in accidents. ODN is working with carriers to help answer this question while helping create a more efficient and fair underwriting process today.

Avvir: “Avvir automates quality assurance for the construction industry, providing real-time insights into the progress and potential defects on a project.”

ClearRoad: “ClearRoad helps government agencies automate toll road pricing for any section of road without the need for traditional proprietary hardware infrastructure.”

Park & Diamond: “Park & Diamond makes biking better by reinventing the bike helmet, using next-generation materials to build a safer, more portable helmet that can roll up into the shape of a water bottle for easier carrying, while looking like a regular hat, cap, or beanie.”

Sapient Industries: “Sapient Industries has developed an autonomous energy management system that senses and learns human behavior in order to eliminate wasted energy in buildings.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Rent the Runway, the fashion startup that began as a rental service for special occasions and has since evolved into a service for people also looking to spice up their everyday wear, just opened up its fifth physical, standalone location. The new location, in downtown San Francisco, enables Rent the Runway members to try on clothes, rent and return them.

Rent the Runway’s launch of a standalone brick-and-mortar location in San Francisco comes after it first opened up a location inside Neiman Marcus. With a standalone location, the company is able to offer longer hours for its members. Instead of opening at 10 a.m. and closing at 7 p.m., Rent the Runway can now stay open from 9 a.m. – 8 p.m. Monday through Friday. It also, of course, has weekend hours.

Thanks to some technology Rent the Runway developed within the last year, it has essentially “legalized shoplifting” for its members, Rent the Runway COO Maureen Sullivan told me yesterday ahead of the store’s launch. Toward the front of the store, there’s a self-return process that enables anyone to quickly return their items. A little farther back in the store, there’s a handful of self-checkout kiosks that let members quickly scan their items and leave.

Photo by Miha Matei Photography

Since its launch about nine years ago, Rent the Runway has launched two additional product offerings. In addition to its standard Reserve product, a one-time rental, Rent the Runway now offers two subscription products. The first is called Unlimited, which lets members rent four items at a time on a constant rotation (meaning you can swap them out as much as you want) for $159 a month.

The second is called Update, which lets you rent just four items for the whole month for $89 per month. In the event someone really likes what they’ve rented, they always have the option to purchase the item at anywhere from 10 percent to 75 percent off. Today, the subscription products make up 50 percent of Rent the Runway’s revenue, with San Francisco as the third largest subscription market.

Photo by Miha Matei Photography

In the nine years or so Rent the Runway has been around, a number of other services have cropped up around fashion. Stitch Fix, which went public last November, and Trunk Club by Nordstrom are two of the big ones. But what differentiates Rent the Runway from the likes of Stitch Fix is that, “they’re trying to get you to buy stuff,” Sullivan said. “You’re still buying things that accumulate in your closet.”

The vision with Rent the runway is to get to the point where 50 percent of your closet is rented, and therefore less cluttered. Rent the Runway, for example, has some customers who wear rented clothes 120 days out of the year.

Rent the Runway currently partners with over 500 brands, and operates as a new type of distribution channel for them. What Rent the Runway offers for brands is marketing and discovery, and customer data.

Down the road, Rent the Runway does envision getting into men’s clothing Sullivan said, but right now, there’s “unprecedented growth” in women’s clothing, so that’s where the focus will be for now.

Back in August, Rent the Runway partnered with Temasek for a $200 million credit facility. Before that deal, Rent the Runway had raised more than $200 million from traditional investors like KPCBC, Highland Capital, Bain Capital, TCV and others.

Powered by WPeMatico