Fundings & Exits

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Few topics garner cheers and groans quite as quickly as the no-code software explosion.

While investors seem uniformly bullish on toolsets that streamline and automate processes that once required a decent amount of technical know-how, not everyone seems to think that the product class is much of a new phenomenon.

On one hand, basic tools like Microsoft Excel have long given non-technical users a path toward carrying out complex tasks. (There’s historical precedent for the perspective.) On the other, a recent bout of low-code/no-code startups reaching huge valuations is too noteworthy to ignore, spanning apps like Notion, Airtable and Coda.

The TechCrunch team was interested in digging in to what defines the latest iteration of no-code and which industries might be the next target for entrepreneurs in the space. To get an answer on what is driving investor enthusiasm behind no-code, we reached out to a handful of investors who have explored the space:

As usual, we’re going to pull out some of the key trends and themes we identified from the group’s collected answers, after which we’ll share their responses at length, edited lightly for clarity and formatting.

Our investor participants agreed that low-code/no-code apps haven’t reached their peak potential, but there was some disagreement in how universal their appeal will prove to various industries. “Every trend is overhyped in some way. Low-code/no-code apps hold a lot of promise in some areas but not all,” Lightspeed’s Raviraj Jain told us.

Meanwhile, Gradient’s Darian Shirazi said “any and all” industries could benefit from increased no-code/low-code toolsets. We can see it either way, frankly.

CapitalG’s Laela Sturdy says the breadth of appeal boils down to finding which industries face the biggest supply constraints of technical talent.

“There just isn’t enough IT talent out there to meet demand, and issues like security and maintenance take up most of the IT department’s time. If business users want to create new systems, they have to wait months or in most cases, years, to see their needs met,” she wrote. “No-code changes the equation because it empowers business users to take change into their own hands and to accomplish goals themselves.”

Mayfield’s Rajeev Batra agreed, saying it would be cool “to see not twenty million developers [building] really cool software but two, three hundred million people developing really cool, interesting software.” If that winds up being the case, the sheer number of monthly-actives in the no and low-code spaces would imply a huge revenue base for the startup category.

That makes a wager on platforms in the space somewhat obvious.

And those bets are being placed. On the topic of valuations and developer interest, our collected interviewees were largely bullish on startup prices (competitive) and VC demand (strong) when it comes to no-code fundraising today.

Sturdy added that the number of early-stage companies in the category “are being funded at an accelerating pace,” noting that her firm is “excitedly watching this young cohort of emerging no-code companies and intend to invest in the trend for years to come.” So, we’re not about to run short of fodder for more Series A and B rounds in the space.

Taken as a whole, like it or not, the no and low-code startup trend appears firm from both a market-fit perspective and from the perspective of investor interest. Now, the rest of the notes.

We’ve seen some skepticism in the market that the low-code/no-code trend has earned its current hype, or product category. Do you agree that the product trend is overhyped, or misclassified?

I don’t think it’s over-hyped, but I believe it’s often misunderstood. No code/low code has been around for a long time. Many of us have been using Microsoft Excel as a low-code tool for decades, but the market has caught fire recently due to an increase in applicable use cases and a ton of innovation in the capabilities of these new low-code/no-code platforms, specifically around their ease of use, the level and type of abstractions they can perform and their extensibility/connectivity into other parts of a company’s tech stack. On the demand side, the need for digital transformation is at an all-time high and cannot be met with incumbent tech platforms, especially given the shortage of technical workers. Low-code/no-code tools have stepped in to fill this void by enabling knowledge workers — who are 10x more populous than technical workers — to configure software without having to code. This has the potential to save significant time and money and to enable end-to-end digital experiences inside of enterprises faster.

What other opportunities does the proliferation of low-code/no-code programs open up when it comes to technical and non-technical folks working more closely together?

This is where things get exciting. If you look at large businesses today, IT departments and business units are perpetually out of alignment because IT teams are resource constrained and unable to address core business needs quickly enough. There just isn’t enough IT talent out there to meet demand, and issues like security and maintenance take up most of the IT department’s time. If business users want to create new systems, they have to wait months or in most cases years to see their needs met. No-code changes the equation because it empowers business users to take change into their own hands and to accomplish goals themselves. The rapid state of digital transformation — which has only been expedited by the pandemic — requires more business logic to be encoded into automations and applications. No code is making this transition possible for many enterprises.

Powered by WPeMatico

Feeling like you should better understand special purpose acquisition vehicles – or SPACs — than you do? You aren’t alone.

It isn’t like you’re totally clueless, right? You’re probably aware that Paul Ryan now has a SPAC, as does baseball executive Billy Beane and Silicon Valley stalwart Kevin Hartz.

You likely know, too, that brash entrepreneur Chamath Palihapitiya seemed to kick off the craze around SPACs — blank-check companies that are formed for the purpose of merging or acquiring other companies — in 2017 when he raised $600 million for a SPAC. Called Social Capital Hedosophia Holdings, it was ultimately used to take a 49% stake in the British spaceflight company Virgin Galactic.

But how do SPACs come together in the first place, how do they work exactly, and should you be thinking of launching one? We talked this week with a number of people who are right now focused on almost nothing but SPACs to get our questions — and maybe yours, too — answered.

Why are SPACs suddenly sprouting up everywhere?

Kevin Hartz — who we spoke with after his $200 million blank-check company made its stock market debut on Tuesday — said their popularity ties in part to “Sarbanes Oxley and the difficulty in taking a company public the traditional route.”

Troy Steckenrider, an operator who has partnered with Hartz on his newly public company, said the growing popularity of SPACs also ties to a “shift in the quality of the sponsor teams,” meaning that more people like Hartz are shepherding these vehicles versus “people who might not be able to raise a traditional fund historically.”

Don’t forget, too, that there are whole lot of companies that have raised tens and hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital and whose IPO plans may have been derailed or slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some need a relatively frictionless way to get out the door, and there are plenty of investors who would like to give them that push.

How does one start the process of creating a SPAC?

The process is really no different than a traditional IPO, explains Chris Weekes, a managing director in the capital markets group at the investment bank Cowen. “There’s a roadshow that will incorporate one-on-one meetings between institutional investors like hedge funds and private equity funds and the SPAC’s management team” to drum up interest in the offering.

At the end of it, institutional investors, which also right now include a lot of family offices, buy into the offering, along with a smaller percentage of retail investors.

Who can form a SPAC?

Pretty much anyone who can persuade shareholders to buy its shares.

What happens right after SPAC has raised its capital?

The money is moved into a blind trust until the management team decides which company or companies it wants to acquire. Share prices don’t really move much during this period as no investors know (or should know, at least) what the target company will be yet.

These SPACs all seem to sell their shares at $10 apiece. Why?

Easier accounting? Tradition? It’s not entirely clear, though Weekes says $10 has “always been the unit price” for SPACs and continues to be with the very occasional exception, such as with hedge fund billionaire Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square Capital Management. (Last month it launched a $4 billion SPAC that sold units for $20 each.)

Have SPACs changed structurally over the years?

They have! Years back, when a SPAC told its institutional investors (under NDA) about the company it had settled on buying, these investors would either vote ‘yes’ to the deal if they wanted to keep their money in, or ‘no’ if they wanted to redeem their shares and get out. But sometimes investors would team up and threaten to torpedo a deal if they weren’t given founder shares or other preferential treatment in what was to become the newly combined company. (“There was a bit of bullying in the marketplace,” says Weekes.)

Regulators have since separated the right to vote and the right to redeem one’s shares, meaning investors today can vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and still redeem their capital, making the voting process more perfunctory and enabling most deals to go through as planned.

I’ve read something about warrants.

That’s because when buying a unit of a SPAC, institutional investors typically get a share of common stock, plus a warrant or a fraction of a warrant, which is a security that entitles the holder to buy more stock of the issuing company at a fixed price at a later date. It’s basically an added sweetener to motivate them to buy into the SPAC.

Are SPACs safer investments than they once were? They haven’t had the best reputation historically.

They’ve “already gone through their junk phase,” suspects Albert Vanderlaan, an attorney in the tech companies group of Orrick, the global law firm. “In the ’90s, these were considered a pretty junky situation,” he says. “They were abused by foreign investors. In the early 2000s, they were still pretty disfavored.” Things could turn on a dime again, he suggests, but over the last couple of years, the players have changed for the better, which is making a big difference.

How much of the money raised does a management team like Hartz and Steckenrider keep?

The rough rule of thumb is 2% of the SPAC value, plus $2 million, says Steckenrider. The 2% roughly covers the initial underwriting fee; the $2 million then covers the operating expenses of the SPAC, from the initial cost to launch it, to legal preparation, accounting, and NYSE or NASDAQ filing fees. It also “provides the reserves for the ongoing due diligence process,” he says.

Is this money like the carry that VCs receive, and do a SPAC’s managers receive it no matter how the SPAC performs?

Yes and yes.

Here’s how Hartz explains it: “On a $200 million SPAC, there’s a $50 million ‘promote’ that is earned.” But “if that company doesn’t perform and, say, drops in half over a year or 18-month period, then the shares are still worth $25 million.”

Hartz calls this “egregious,” though he and Steckenrider formed their SPAC in exactly the same way rather than structure it differently.

Says Steckrider, “We ultimately decided to go with a plain-vanilla structure [because] as a first-time SPAC sponsor, we wanted to make sure that the investment community had as easy as a time as possible understanding our SPAC. We do expect to renegotiate these economics when we go and do the [merger] transaction with the partner company,” he adds.

Does a $200 million SPAC look to acquire a company that’s valued at around the same amount?

No. According to law firm Vinson & Elkins, there’s no maximum size of a target company — only a minimum size (roughly 80% of the funds in the SPAC trust).

In fact, it’s typical for a SPAC to combine with a company that’s two to four times its IPO proceeds in order to reduce the dilutive impact of the founder shares and warrants.

In the case of Hartz’s and Steckenrider’s SPAC (it’s called “one”), they are looking to find a company “that’s approximately four to six times the size of our vehicle of $200 million,” says Hartz, “so that puts us around in the billion dollar range.”

Where does the rest of the money come from if the partner company is many times larger than the SPAC itself?

It comes from PIPE deals, which, like SPACs, have been around forever and come into and out of fashion. These are literally “private investments in public equities” and they get tacked onto SPACs once management has decided on the company with which it wants to merge.

It’s here that institutional investors get different treatment than retail investors, which is why some industry observers are wary of SPACs.

Specifically, a SPAC’s institutional investors — along with maybe new institutional investors that aren’t part of the SPAC — are told before the rest of the world what the acquisition target is under confidentiality agreements so that they can decide if they want to provide further financing for the deal via a PIPE transaction.

The information asymmetry seems unfair. Then again, they’re restricted not only from sharing information but also from trading the shares for a minimum of four months from the time that the initial business combination is made public. Retail investors, who’ve been left in the dark, can trade their shares any time.

How long does a SPAC have to get all of this done?

It varies, but the standard is around two years.

And if they can’t get it done in the designated time frame?

The money goes back to shareholders.

What do you call that phase of the deal after the partner company has been identified and agrees to merge, but before the actual combination?

That’s called the de-SPAC’ing process, and during this stage of things, the SPAC has to obtain shareholder approval, followed by a review and commenting period by the SEC.

Toward the end of this stretch — which can take 12 to 18 weeks altogether — bankers start taking out the new operating team in the style of a traditional roadshow and getting the story out to analysts who cover the industry so that when the combined new company is revealed, it receives the kind of support that keeps public shareholders interested in a company.

Will we see more people from the venture world like Palihapitiya and Hartz start SPACs?

Weekes, the investment banker, says he’s seeing less interest from VCs in sponsoring SPACs and more interest from them in selling their portfolio companies to a SPAC. As he notes, “Most venture firms are typically a little earlier stage investors and are private market investors, but there’s an uptick of interest across the board, from PE firms, hedge funds, long-only mutual funds.”

That might change if Hartz has anything to do with it. “We’re actually out in the Valley, speaking with all the funds and just looking to educate the venture funds,” he says. “We’ve had a lot of requests in. We think we’re going to convert [famed VC] Bill Gurley from being a direct listings champion to the SPAC champion very soon.”

In the meantime, asked if his SPAC has a specific target in mind already, Hartz says it does not. He also takes issue with the word “target.”

Says Hartz, “We prefer ‘partner company.’” A target, he adds, “sounds like we’re trying to assassinate somebody.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Vertical farming technology provider iFarm has bagged a $4 million seed round, led by Gagarin Capital, an earlier investor in the startup. Other investors in the round include Matrix Capital, Impulse VC, IMI.VC and several business angels.

The Finnish startup is focused on providing software that enables others to carry out vertical farming — targeting sales at food processing companies and FMCG giants, as well as farmers, university research centers and even large corporates with their own catering needs as a result of operating large physical office footprints.

Its software as a service platform automates crop care for plants such as salad greens, cherry tomatoes and berries grown in vertical stacks. The system involves a range of technologies to monitor and automate crop care, applying computer vision and machine learning and drawing on data on “thousands” of plants collected from a distributed network of farms, per iFarm .

At this stage it’s providing technology to around 50 projects in Europe and the Middle East — covering a total of 11,000 square meters of farm. Its platform is currently able to automate care for around 120 varieties of plants, with the goal of getting to 500 by 2025 (it says 10 new crop varieties are being added each month).

“iFarm started three years ago, with three founders. The goal is to build technology… for growing tasty and healthy food that we already eat,” says co-founder and CEO Max Chizhov, who notes the business has grown to 15 employees along the way.

“We started from a greenhouse. First year just looking for technologies — which kind of technologies to use. After one year of experiments we have some pilots and now we are focused on indoor farming, vertical farming.”

Vertical farming is an urban farming technique that involves stacking plants in dense layers in a highly controlled indoor environment, using LED lighting to replace sunlight to power all-year-round agriculture.

Furthermore, iFarm notes that the fully automated approach also means there’s no need for pesticides to grow a range of edible greens, herbs, fruits, flowers and vegetables. There are some natural limits on what can be grown within such systems — taller plants and trees obviously can’t be squeezed into stacks. Deep-root vegetables also aren’t suitable, although iFarm touts baby carrots among its product portfolio.

“We focus on profitable products,” says Chizhov. “Small crops, very fast growing crops, and easy to irrigate and easy to grow in many layers. Many layers is the advantage of indoor farms.”

Photo credit: iFarm

While there are now hundreds of vertical farming startups whose business model is fixed on selling the edible produce they grow, such as to supply supermarkets and other food retailers, iFarm is purely focused on developing technologies to support automated indoor agriculture.

So it might, for instance, be eyeing the likes of Infarm, Bowery and Plenty as potential customers for its vertical farming optimization technologies.

It says its systems can be applied to vertical farms of 20 to 20,000 square meters, supporting scalability.

“Our main advantage is we know how to grow and you don’t need any special technologies to know how to grow. All of our algorithms, all of the data, is based in our software,” says Chizhov, emphasizing the software is hardware agnostic — meaning customers don’t need to use iFarm’s kit for their vertical farms but just can apply its algorithms to their own set-ups.

The company has designed various bits of vertical farm hardware it can supply, or co-develop with customers, per Chizhov, such as fertilizer units and LED lighting. But the software as a service platform isn’t locked to any specific piece of kit.

“The main thing is the software that combines optimization systems like humidity, temperature, CO2 etc; and some business separations — like why, how, when we start growing, which clients,” he says, adding: “It’s like a CRM plus an ERP system that controls all the parameters.

“In this system we use computer vision systems. We use AI for increasing taste [of the edible produce], increasing yield parameters of our growing crops. We also use drones which fly in our farms and observe all of our greens and all of our plants. We optimize all of the processes in the farm using software and some [pieces of hardware] that use the software.”

Chizhov says the seed funding will be used to gradually expand the business into new regions — with a launch into the U.S. market on the cards in two years’ time — but the main priority now is to spend on further software development.

“The main goal is [adding] new type of crops,” he notes. “Research, development, new products.”

On the competitive front, iFarm is not the only technology provider seeking to sell to the burgeoning vertical farming sector. Chizhov says there are around 10 to 15 similar agtech startups. But he contends its tech and approach has the edge over the likes of U.K.-based Intelligent Growth Solutions, Belgium’s Urban Crop Solutions, Switzerland’s Growcer, U.S. “container farms” provider Freight Farms or China’s Alesca Life, to name-check a handful of other players in the space.

“There are some companies in this market that also provide solutions but with less optimization, with less software value and with less product mix/product line,” he argues. “The main difference is the type of crops; it’s software that we provide for our clients — because you don’t need to know how to grow; you don’t need to be a specialist in your company, you just push a button. And we provide excellent services for our clients. Design, installation, operation, help to sell the final product, etc.”

Chizhov also notes iFarm has filed patents to protect some of its technologies.

Photo credit: iFarm

Mikhail Taver, GP of Gagarin Capital, who is the lead investor in iFarm’s seed round, says the startup stood out on account of having a competitive advantage in the sector. Although he also notes that the fund’s agtech strategy is focused on indoor farming rather than mainstream outdoors — which again makes iFarm a good fit.

“We do see a large potential in the sector with the [world’s] rising population. We see the increasing demand for food — it’s only going to continue. We see global warming and general sustainability issues. And iFarm seems to be able to solve most of those,” Taver told TechCrunch.

“I don’t really see much competitors able to grow things other than greens,” he added, elaborating on the competitive edge claim. “You don’t normally get proper tomatoes or edible flowers and things like that grown in vertical farms. They mainly concentrate on a couple of salads at most.

“Plus most of our competitors they focus on competing with actual farmers, whereas we’re trying to augment them. We don’t try to force them off the market — we’re trying to help them get bigger. Which is a totally different approach and it should be working better. At least that’s what I believe.”

This article was updated with a correction: We were originally given the incorrect job title for Max Chizhov; he is in fact CEO, not CBDO.

Powered by WPeMatico

Thinking back to the last time I accepted a job, I can’t recall actually reading any of the material that was sent over. I think I skimmed some docs to make sure the numbers written down matched what I had been told over the phone, but after that it was a blur of digital signing and emailing and precisely no due diligence from myself.

Not great, really. I bet that your experience accepting new gigs has been somewhat similar. In startups, jobs are offered with exotic types of pay, chock full of startup stock options in all their 409A and vesting-period glory. Some folks might not really understand what is being offered. Like what the value of their full comp package really is, when performance pay and other sweeteners are stacked on top of base rates. With remote learning in the equation, it’s even more confusing.

This is the market space that Welcome, a startup that is announcing a $1.4 million fundraise, wants to fix. (Update: Forgot to add the capital sources, which include Ludlow Ventures, the Weekend Fund, Global Founders Capital, both Shrug and Basement, as well as a number of angels.)

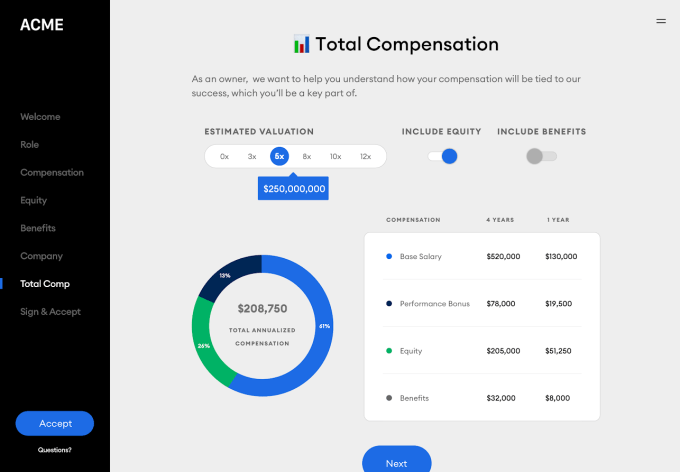

The company told TechCrunch it is a “first offer management and closing platform.” Its service helps provide a clear picture of total comp to candidates, helping them accept or deny an offer that they can fully understand.

Here’s a screengrab from the candidate’s side of the employer-employee divide:

If “offer management and closing” sounds like a small niche to target, it both is and is not.

It is, in that if Welcome stayed in its current market-position forever it would have a smaller product target than most startups. But the company has plans to expand its product-set over time. For example, its co-founders Nick Gavronsky and Rick Pereira explained that Welcome wants to offer real-time salary data in the future, based on the information that will flow through its service.

Want to close an engineer in North Carolina with a high level of confidence in the offer? Welcome should be able to tell you, later on, what a comp package should look like if you want make sure the candidate will accept.

Gavronsky and Pereira have experience in product and people work, respectively, making their union at Welcome a good fit. The company’s team is currently just four folks, though the startup expects that it will double in size this year. The capital it raised in January, but is only talking about now, is making the hiring possible.

Now, the $1.4 million number is pretty dated. Normally I’d skip over a round so far from the past, but Welcome caught my eye, as I’ve recently written about another HR tech provider, Sora, and the Welcome deal felt like an illustrative event: This is how seed rounds are announced, long after the fact, which makes reporting on seed-stage trends really hard. Something to keep in mind.

Welcome is barking up a winsome tree with its product, not only because the offer/offer acceptance process is garbage today — let’s email some PDFs and hand a candidate off between departments! — but because it has seen strong early demand from potential customers. Its service is currently in a private alpha that was a bit oversubscribed, though the company is not yet charging for its service. (Welcome will be a SaaS play, priced on company size, which seems reasonable.)

Past all that, what’s exciting about Welcome is that if it can get a number of customers aboard when it makes it to beta or launch, the company will have placed itself in a position where it can expand in several directions. It could, for example, extend its feature set to help with pre-onboarding or onboarding itself, given that it already knows a new candidate and their new employer. Of course, the startup wants to talk more about what it’s building today, but it’s also fun to look ahead.

That’s enough on Welcome, we’ll chatter about them again when they formally launch, or share some neat growth metrics. Until then, good luck getting into the alpha.

Powered by WPeMatico

Taiwanese startup iKala, which offers an artificial intelligence-based customer acquisition and engagement platform, will expand into new Southeast Asian markets after raising a $17 million Series B. The round was led by Wistron Digital Technology Holding Company, the investment arm of the electronics manufacturer, with participation from returning investors Hotung Investment Holdings Limited and Pacific Venture Partners. It brings iKala’s total raised so far to $30.3 million.

The new funding will be used to launch in Indonesia and Malaysia, and expand in markets where iKala already operates, including Singapore, Thailand, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Vietnam and Japan. Wistron Digital Technology Holding Company, which also offers big data analytics, will serve as a strategic investor, and this also marks the Taiwanese firm’s entry into Southeast Asia.

IKala’s products are targeted toward e-commerce companies, and include KOL Radar, for influencer marketing, and Shoplus, a social commerce service focused on Southeast Asian markets.

In a statement about the funding, iKala board member Lee-feng Chien, former managing director at Google Taiwan, said, “Taiwan has an excellent reputation for having some of the best high-tech talents in both hardware and software around the region. With Wistron as a strategic partner, iKala can become a major driving force for transforming Taiwan into an AI industry and talent hub in Asia.”

While Taiwan’s technology industry is best-known for hardware, especially semiconductor manufacturers like Foxconn and TSMC, a new crop of startups are helping the country establish a reputation for AI prowess.

In addition to iKala, these include Appier, which also provides a customer analytics, and enterprise translation platform WritePath. Big American tech companies, including Amazon, Google and Microsoft, have also set up AI-focused research and development centers in Taiwan, drawing on the country’s engineering talent and government programs.

Powered by WPeMatico

In Indonesia, about half of adults are “underbanked,” meaning they don’t have access to bank accounts, credit cards and other traditional financial services. A growing list of tech companies are working on solutions, from Payfazz, which operates a network of financial agents in small towns, to digital payment services from GoJek and Grab. As a result, financial inclusion is increasing for consumers and small businesses in Southeast Asia’s largest country, but one group remains underserved: schools.

InfraDigital was founded in 2018 by chief executive officer Ian McKenna and chief operating officer Indah Maryani. Both have backgrounds in financial tech, and their platform enables parents to pay school tuition with the same digital services they use for electricity bills or online shopping. The startup currently serves about 400 schools and recently raised a Series A led by AppWorks.

Many Indonesian schools still rely on cash payments, which are often delivered by kids to their teachers.

“My kid had just started school, and one day I spotted my wife giving him an envelope full of cash for tuition. He was only three years old,” McKenna said. “That triggered my curiosity about how these financial systems work.”

To give parents an easier alternative, InfraDigital, which is registered with Indonesia’s central bank, partners with banks, convenience store chains like Indomaret, online wallets and digital payment services like GoPay to allow them to send tuition money online.

“The way you pay your electricity bill, it’s likely that your school is already there, regardless of whether you have a bank account or live in a really remote place” where many people make cash payments for services at convenience stores, McKenna said. The startup is now working on a system for schools in areas that don’t have access to convenience store chains and banks.

Before building InfraDigital’s network, McKenna and Maryani had to understand why many schools still rely on cash payments and paper ledgers to manage tuition.

“Banks have been trying to tap into the education market for a long time, 12 to 15 years probably, but no one has become the biggest bank for schools,” said Maryani. “The reason behind that is because they come in with their own products and they don’t try to resolve the issues schools are facing. Since they are focused on the consumer side, they don’t really see schools or other offline businesses as their customers, and there is a lot of customization that they need to do.”

For example, a school might have 2,000 students and charge each of them about USD $10 a month in school fees. But they also collect separate payments for books, uniforms, and building fees. InfraDigital’s founders say schools typically send out an average of about 2.5 invoices a month.

Digitizing payments also makes it easier for schools to track their finances. InfraDigital provides its clients with a backend application for accounting and enrollment management. It automatically tracks tuition payments as they come in.

“People don’t get paid that much and they are ridiculously busy taking care of thousands of kids. It’s really, really tough,” McKenna said. “When you’re giving them a solution, it’s not about features, it’s not about tools, it’s about the practicalities of their day-to-day life and how we are going to assist them with it. So you remove that burden from them.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in movement restriction orders in different areas of Indonesia, InfraDigital’s founders say the platform was able to forecast trends even before schools officially closed. They started surveying schools in their client base, and sent back data to help them forecast how school closures would affect their income.

“From the school’s perspective, it’s a really damaging situation, with 30% to 60% income drops. Teachers don’t get paid. If the economy goes down, parents at lower-income schools, which are a big part of our client base, won’t be able to pay,” McKenna said. “It’s built into the model, and we’ll continue seeing that however long the economic impact of COVID-19 lasts.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Buildkite, a Melbourne-based company that provides a hybrid continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD) platform for software developers, announced today that it has raised AUD $28 million (about USD $20.2 million) in Series A funding, bringing its valuation to more than AUD $200 million (about USD $145 million).

The funding was led by OpenView, an investment firm that focuses on growth-stage enterprise software companies, with participation from General Catalyst.

This round is the company’s first since Buildkite raised about AUD $200,000 in seed funding when it was founded in 2013.

Co-founder and chief executive officer Lachlan Donald told TechCrunch that Buildkite didn’t seek more funding earlier because it was growing profitably. In fact, the company turned away interested investors “because we wanted to focus on sustainable growth and maintain control of our destiny.”

But Donald said they were open to investment from OpenView and General Catalyst because they see the two investors as “true partners as we enter and define this next generation of CI/CD.”

Buildkite’s team is small, with just 26 employees. “We’re a lean, focused team, so their expert advice and guidance will help more software teams around the world discover Buildkite,” Donald said. He added that part of the funding round will be used to give 42X returns to early investors and shareholders, and the rest will be used on product development.

In a statement about the funding, OpenView partner Mackey Craven said, “The global pandemic and the resulting economic uncertainty underlines the importance for companies to maximize efficiencies and build for growth. As the world continues to build digital-first applications, we believe Buildkite’s unique approach will be the new enterprise standard of CI/CD and we’re excited to be supporting them in realizing this ambition.”

Continuous integration gives software teams an automated way to develop and test applications, making collaboration more efficient, while continuous delivery refers to the process of pushing code to environments for further testing by other teams, or deploying it to customers. CI/CD platforms make it easier for fast-growing tech companies to test and deliver software. Buildkite says it now has more than 1,000 customers, including Shopify, Pinterest and Wayfair.

As part of the round, Jean-Michel Lemieux, Shopify’s chief technology officer, and Ashley Smith, chief revenue officer at Gatsby and OpenView venture partner, will join Buildkite’s board.

The increased use of online applications caused by the COVID-19 pandemic means there is more demand for CI/CD platform, since engineering teams need to work more quickly.

“A good example is Shopify, one of our longstanding partners. They came to us after they outgrew their previous hosted CI provider,” Donald said. “Their challenge is one we see across all of customers — they needed to reduce build time and scale their team across multiple time zones. Once they wrapped Buildkite into their development flow, they saw a 75% reduction in build wait times. They grew their team by 300% and have still been able to keep build time under 10 minutes.”

Other CI platforms available include Jenkins, CircleCI, Travis, Codeship and GitLab. Co-founder and chief technology officer Keith Pitt said one of the ways that BuildKite differentiates from its rivals is its focus on security, which prompted his interest in building the platform in the first place.

“Back in 2013, my then-employer asked that I stop using a cloud-based CI/CD platform due to security concerns, but I found the self-hosted alternatives to be incredibly outdated,” Pitt said. “I realized a hybrid approach was the solution for testing and deploying software at scale without compromising security or performance, but was surprised to find a hybrid CI/CD tool didn’t exist yet. I decided to create it myself, and Buildkite was born.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Movable Ink, a company that helps businesses deliver more personalized and relevant email marketing, is announcing that it has raised $30 million in Series C funding.

The company will be 10 years old in October, and founder and CEO Vivek Sharma told me that it’s always been “capital efficient” — even with the new round, Movable Ink has only raised a total of $39 million.

However, Sharma noted that with COVID-19, it felt like “a good idea to have some dry powder on our balance sheet … if things turned south.”

At the same time, he suggested that the pandemic’s impact has been more limited than he anticipated, and has been “really focused” on a few sectors like travel, hospitality and “old line retailers.”

“Those who are adopting to e-commerce really quickly have done well, financial services has done well, media has done well,” he said.

The company’s senior vice president of strategy Alison Lindland added that clients using Movable Ink were able to move much more quickly, with campaigns that would normally take months launching in just a few days.

“We really saw those huge, wholesale digital transformations in a time of duress,” Lindland said. “Obviously, large Fortune 500 companies were making difficult decisions, were putting vendors on hold, but email marketers are always the last people furloughed themselves, because of how critical email marketing is to their businesses. We were just as critical to their operations.”

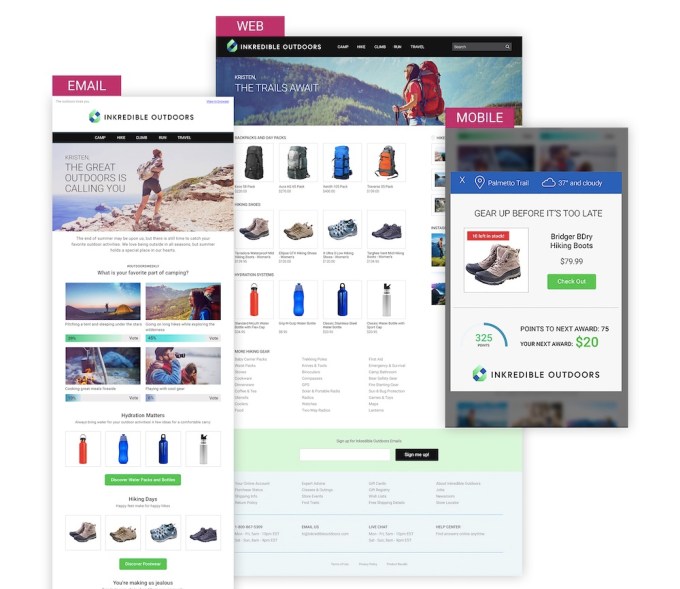

Image Credits: Movable Ink

The company said it now works with more than 700 brands, and in the run up to the 2020 election, its customers include the Democratic National Committee.

The new funding comes from Contour Venture Partners, Intel Capital and Silver Lake Waterman. Sharma said the money will be spent on three broad categories: “Platforms, partners and people.”

On the platform side, that means continuing to develop Movable Ink’s technology and expanding into new channels. He estimated that around 95% of Movable Ink’s revenue comes from email marketing, but he sees a big opportunity to grow the web and mobile side of the business.

“We take any data the brand has available to it and activate and translate it into really engaging creative,” he said, arguing that this approach is applicable in “every other channel where there’s pixels in front of the consumer’s eyes.”

The company also plans to make major investments into AI. Sharma said it’s too early to share details about those plans, but he pointed to the recent hire of Ashutosh Malaviya as the company’s vice president of artificial intelligence.

As for partners, the company has launched the Movable Ink Exchange, a marketplace for integrations with data partners like Oracle Commerce Cloud, MessageGears Engage, Trustpilot and Yopto.

And Movable Ink plans to expand its team, both through hiring and potential acquisitions. To that end, it has hired Katy Huber as its senior vice president of people.

Sharma also said that in light of the recent conversations about racial justice and diversity, the company has been looking at its own hiring practices and putting more formal measures in place to track its progress.

“We use OKRs to track other areas of the business, so if we don’t incorporate [diversity] into our business objectives, we’re only paying lip service,” he said. “For us, it was really important to not just have a big spike of interest, and instead save some of that energy so that it’s sustained into the future.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Robinhood announced this morning that it has raised $200 million more at a new, higher $11.2 billion valuation. The new capital came as a surprise.

Astute observers of all things fintech will recall that Robinhood, a popular stock trading service, has raised capital multiple times this year, including an initial $280 million round at an $8.3 billion valuation, and a later $320 million addition that brought its valuation to $8.6 billion.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money. You can read it every morning on Extra Crunch, or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

Those rounds, coming in May and July, now feel very passé in the sense that they are frightfully cheap compared to the price at which Robinhood just added new funds. D1 Partners — a private capital pool founded in 2018 — led the funding.

The unicorn’s new nine-figure tranche, a Series G, values the firm at $11.2 billion. A $2.6 billion bump in about a month is an impressive result, one that points to an inescapable conclusion: Robinhood is still growing, and fast.

How fast is the question. There are three things to bring up in this regard: Trading growth at Robinhood, the company’s soaring incomes from selling order flow to other financial institutions, and, oddly enough, crypto. Let’s peek at each and come up with a good why as to the new Robinhood valuation.

After all, we’re going to see an IPO from this company before the markets get less interesting, if it’s smart.

Robinhood is currently walking a line between enthusiasm that its trading volume is growing and conservatism, arguing that its userbase is not majority-comprised of day traders. The company is stuck between the need for huge revenue growth and keeping pedestrian users from tanking their net worth with unwise options bets.

It’s worth noting that Robinhood spent a lot of its funding round announcement email to TechCrunch talking about its users safety and education work. It makes sense given that we know that the company is seeing record trades, and record incomes from options themselves. After a Robinhood user killed themself after misunderstanding an options trade on the platform, Robinhood pledged to do better. We’re keeping tabs on how well it manages to meet the mark of its promise.

But back to the revenue game, let’s talk volume. On the trading front Robinhood has lots of darts. And by darts we mean daily average revenue trades. Robinhood had 4.31 million DARTs in June, with the company adding that “DARTs in Q2 more than doubled compared to Q1” in an email.

The huge gain in trading volume does not mean that most Robinhood users are day trading, but it does imply that some are given the huge implied trading volume results that the DARTs figure points to. Robinhood saw around 129,300,000 trades in June, which is 30 days. That’s a lot!

Powered by WPeMatico

At Disrupt this year TechCrunch is digging into the $100 million annual recurring revenue (ARR) threshold. To help us explore the software revenue milestone, we’re bringing in a number of CEOs that have already reached it: Egnyte’s Vineet Jain, GitLab’s Sid Sijbrandij and Kaltura’s Michal Tsur.

Join us on the Extra Crunch stage to hear this session, along with several other sessions around how founders can navigate the choppy startup waters. You can snag a ticket here.

The modern software world, often called software as a service, or SaaS, operates against a well-defined set of inflection points. These include $1 million ARR, a key moment for startups looking to raise their first Series-defined round of capital; the $10 million ARR mark, at which point the same companies become hard to kill; and $100 million ARR, at which point startups can start to prep for a public offering, or regular, large capital raises from private investors.

It’s that last milestone we want to explore. With three executives from companies that we’ve included in our series on $100 million ARR companies, we’ll dig into what they had to learn the hard way as they grew to material business scale, what went well and what they might be able to share with startups that aspire to a similar level of success.

That we’ll be hosting the conversation during a mini-IPO wave will make it all the more exciting; these three business leaders will certainly have at least one eye on the public markets. And as we’ll have the chat in the shadow of COVID-19, we’ll learn about how the highly valued private companies have had to adapt to a changed economic environment and working setup.

We’ll lean into lessons, learnings and other operational questions with the CEO of Egnyte, an enterprise content and management service provider; the CEO of GitLab, a DevOps company that has long had a distributed-employee model that is incredibly pertinent to the current moment; and the president of Kaltura, a software company that powers online video for other companies.

Since TechCrunch started compiling a list of companies that had either reached $100 million ARR, or were on their way, we’ve collected dozens of firms to the list. The three we’re talking to are among the most interesting. At a minimum, the conversation should be an interesting look into the next set of leaders in the software and startup space. See you there.

You can read our entries from the $100 million ARR series on each firm below:

Disrupt is happening for five action-packed days — September 14-18 — and if you want to partake in this session (or any other session on the Extra Crunch stage), you’ll need to get your Digital Pro Pass for just $345 for a limited time. Or if you are a founder, showcase your startup in Digital Startup Alley for just $445 for you PLUS another member of your team. Get your pass today!

Powered by WPeMatico