funding

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

KitchenMate is a Toronto-based startup promising businesses a fresh approach to feeding their employees.

The startup has raised $3.5 million in seed funding led by Eniac Ventures and Golden Ventures, with participation from FJ Labs and Techstars. It’s also expanding into the United States.

Founder and CEO Yang Yu said KitchenMate was founded with the goal of providing “healthy meals at an affordable cost.” The solution he and his team developed combines refrigerated, tamper-proof “smart meal-pods” containing fresh, prepared meals that are then heated in a “smart cooker.”

You might think a pandemic is the wrong time for this idea, since so many companies are still working from home. And Yu acknowledged that some of KitchenMate’s most likely customers (such as tech companies) don’t need the product right now.

At the same time, he said there are many “old-school companies” in industries like manufacturing, distribution and essential services that can’t operate that way — and in those sectors, business is “booming.”

“[Before the pandemic,] it was a nice-to-have for a lot of companies that care about employees and want to offer them a healthy meal,” he said. “It’s become a must-have for a lot of companies now that everything is closed.”

In other words, Yu said that with many restaurants and other businesses shuttered by the pandemic, KitchenMate has emerged for some employers as “the only option.” He also said it’s being used by hospitals as an efficient way to prepare healthy meals for patients.

Without a KitchenMate Smart Cooker at home, I can’t vouch for the quality of the food, but Yu showed me how he prepared a meal in the KitchenMate office: He opened the refrigerator, removed a Smart Meal-Pod and scanned it with his phone, then loaded the Meal-Pod into the cooker. A few minutes later, a tasty-looking lunch of rice, curry, vegetables and tofu was ready for him.

KitchenMate offers the equipment for sale or rent to employers. The meals are then purchased by employees via smartphone app at an average cost of $9, usually with employees paying $7 and employers subsidizing the rest.

KitchenMate delivers new Meal-Pods once or twice a week, and teams can influence what gets delivered by voting on the dishes that they want. The startup also offers an option where staff members can prepare the meals for employees, rather than having everyone raid the refrigerator and making meals for themselves.

Yu suggested that as offices reopen, people will want to avoid crowded cafeterias, and they’ll choose KitchenMate’s bulk deliveries over having lots of individual deliveries going in and out of buildings and elevators.

Yu acknowledged that there is a risk of a “backlog” in the kitchen if everyone wants their lunch at the same time, but he said KitchenMate tries to alleviate this issue by allowing people to pre-order their meals in the app.

“We create more flexibility around people eating for a lot of companies who either can’t afford catering or, post-COVID, it’s just not possible anymore to have shared meals,” he said.

Powered by WPeMatico

Warby Parker, the optical e-commerce giant, has today announced the close of a $245 million funding round from D1 Capital Partners, Durable Capital Partners, T. Rowe Price and Baillie Gifford.

A source familiar with the company’s finances confirmed to TechCrunch that this brings Warby Parker’s valuation to $3 billion.

The fresh $245 million comes as a combination of a Series F round ($125 million led by Durable Capital Partners in Q2 of this year) and a Series G round ($120 million led by D1 Capital in Q3 of this year). Neither of the two rounds was previously announced.

In the midst of COVID-19, Warby has also pivoted a few facets of its business. For one, the company’s Buy A Pair, Give A Pair program, which has focused on vision services across the globe, pivoted to stopping the spread of COVID-19 in high-risk countries. The company also used their Optical Lab in New York as a distribution center to facilitate the donation of N95 masks to healthcare workers.

The company has also launched a telehealth service for New York customers, allowing them to extend an existing glasses or contacts prescription through a virtual visit with a Warby Parker OD, and expanded its Prescription Check app to new states.

Warby Parker was founded 10 years ago to sell prescription glasses online. At the time, e-commerce was still relatively nascent and the idea of direct-to-consumer glasses was novel, to say the least. By cutting out the cost of physical stores, and competing with an incumbent who had for years enjoyed the luxury of overpricing the product, Warby was able to sell prescription glasses for less than $100/frame.

Of course, it wasn’t as simple as throwing up a few pictures of frames on a website and watching the orders pour in. The company developed a process where customers could order five potential frames to be delivered to their home, try them on, and send them back once they made a selection.

Since, the company has expanded into new product lines, including sunglasses and children’s frames, as well as expanding its footprint with physical stores. In fact, the company has 125 stores across the U.S. and in parts of Canada.

Warby also developed the prescription check app in 2017 to allow users to extend their prescription through a telehealth check up.

In 2019, Warby launched a virtual try-on feature that uses AR to allow customers to see their selected frames on their own face.

The D2C giant, in its 10 years of existence, has balanced its technological innovation with its physical expansion, which could explain its newfound triple-unicorn status. These latest rounds bring Warby Parker’s total funding to $535.5 million.

Powered by WPeMatico

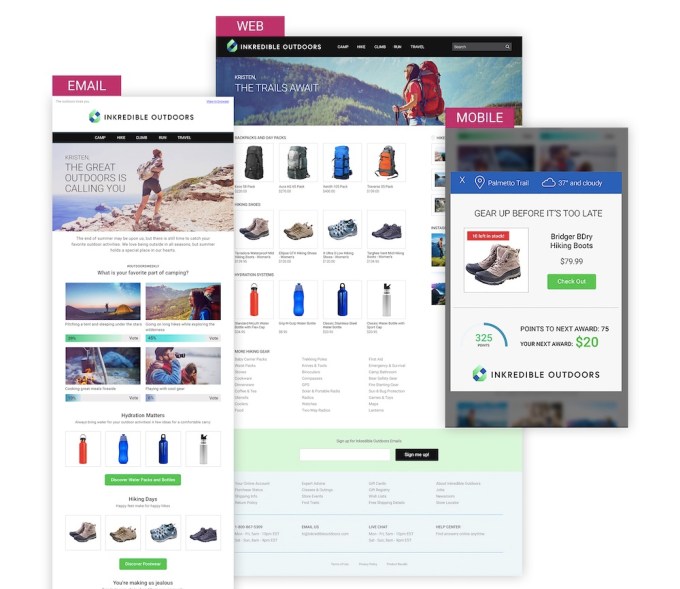

Narrative has raised $8.5 million in Series A funding and is launching a new product designed to further simplify the process of buying and selling data.

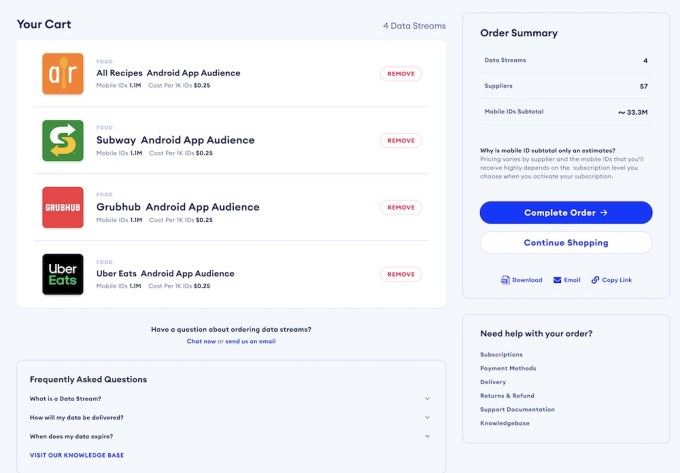

I’ve already written about the company’s existing marketplace and software for managing data transactions. With the new Data Streams Marketplace, the process should be simpler than ever — not much different than buying products on Amazon.

“Essentially, the idea was to take the best parts of the e-commerce and search models and apply that to a non-consumer offering to find, discover and ultimately buy data,” founder and CEO Nick Jordan (pictured above on the left) told me. “The premise is make it as easy to buy data as it is to buy stuff online.”

For example, Jordan showed me how a marketer could browse and search for different types of data in the marketplace. Once they find something they want to purchase (say, the mobile IDs of people who have the Uber Driver app installed on their phones, or the Zoom app) at a price they’re willing to pay (usually via subscription), they can just add the data set to their shopping cart, enter their credit card information, accept the terms of service and check out.

In Jordan’s view, this approach has become more attractive in recent months, because with all the uncertainty, companies need more data, and they need it quickly. For example, he suggested that a large company spending tens of millions of dollars on advertising “needs a way to find and buy the data almost programmatically and have the whole thing take five minutes instead of five months — those are the orders of magnitude we’re talking about here.”

Image Credits: Narrative

This data is generally sold by third-party sellers who are vetted by Narrative before they join the platform. Jordan also said the marketplace allows buyers to learn more about who they’re buying data from and even to establish a direct relationship — something that could be important for understanding things like regulatory compliance and data quality.

Although Narrative works to “deeply understand [sellers’] data collection methodologies,” Jordan warned, “There’s not necessarily a silver bullet for things being safe from a regulatory perspective.”

Similarly, he said that Narrative isn’t going to be grading the quality of the data sold on the platform. He argued, “Data quality is in the eye of the beholder. Someone’s signal is someone else’s noise.”

The goal with both of these issues is to provide transparency and allow buyers to do more research when necessary. Jordan also said Narrative is building out a marketplace of third-party applications — and that could include applications that score the quality of a data set.

“In the long run, I can imagine a number of use cases that’s almost infinite,” he said.

Narrative had previously raised $5.3 million in funding, according to Crunchbase. The Series A was led by G20 Ventures, with additional funding from existing investors Glasswing Ventures, MathCapital, Revel Partners, Tuhaye Venture Partners and XSeed Capital.

Jordan said the new round will allow the company to hire in areas like product, engineering, sales and marketing. He also noted that Narrative has long prioritized hiring team members from across North America, and recently it’s been placing a bigger focus on outreach and hiring from underrepresented groups.

“It’s easier said than done,” he acknowledged. “Any company that’s doing it well has to make it a priority and not just something they hope happens.”

Powered by WPeMatico

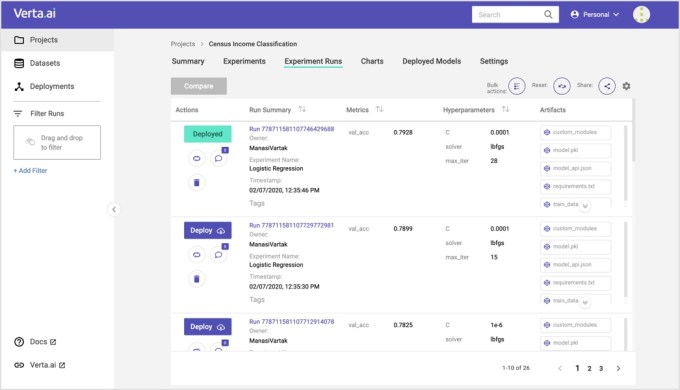

Manasi Vartak, founder and CEO of Verta, conceived of the idea of the open-source project ModelDB database as a way to track versions of machine models while she was still in grad school at MIT. After she graduated, she decided to expand on that vision to build a product that could not only track model versions, but provide a way to operationalize them — and Verta was born.

Today, that company emerged from stealth with a $10 million Series A led by Intel Capital with participation from General Catalyst, which also led the company’s $1.7 million seed round.

Beyond providing a place to track model versioning, which ModelDB gave users, Vartak wanted to build a platform for data scientists to deploy those models into production, which has been difficult to do for many companies. She also wanted to make sure that once in production, they were still accurately reflecting the current data and not working with yesterday’s playbook.

“Verta can track if models are still valid and send out alarms when model performance changes unexpectedly,” the company explained.

Image Credits: Verta

Vartak says having that open-source project helped sell the company to investors early on, and acts as a way to attract possible customers now. “So for our seed round, it was definitely different because I was raising as a solo founder, a first-time founder right out of school, and that’s where having the open-source project was a huge win,” she said.

Certainly Mark Rostick, VP and senior managing director at lead investor Intel Capital, recognized that Verta was trying to solve a fundamental problem around machine learning model production. “Verta is addressing one of the key challenges companies face when adopting AI — bridging the gap between data scientists and developers to accelerate the deployment of machine learning models,” Rostick said.

While Vartak wasn’t ready to talk about how many customers she has just yet at this early stage of the company, she did say there were companies using the platform and getting models into production much faster.

Today, the company has 9 employees, and even at this early stage, she is taking diversity very seriously. In fact, her current employee makeup includes four Indian, three Caucasian, one Latino and one Asian, for a highly diverse mix. Her goal is to continue on this path as she builds the company. She is looking at getting to 15 employees this year, then doubling that by next year.

One thing Vartak also wants to do is have a 50/50 gender split, something she was able to achieve while at MIT in her various projects, and she wants to carry on with her company. She is also working with a third party, Sweat Equity Ventures, to help with recruiting diverse candidates.

She says that she likes to work iteratively to build the platform, while experimenting with new features, even with her small team. Right now, that involves interoperability with different machine learning tools out there like Amazon SageMaker or Kubeflow, the open-source machine learning pipeline tool.

“We realized that we need to meet customers where they are at their level of maturity. So we focused a lot the last couple of quarters on building a system that was interoperable so you can pick and choose the components kind of like Lego blocks and have a system that works end to end seamlessly.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Feeling like you should better understand special purpose acquisition vehicles – or SPACs — than you do? You aren’t alone.

It isn’t like you’re totally clueless, right? You’re probably aware that Paul Ryan now has a SPAC, as does baseball executive Billy Beane and Silicon Valley stalwart Kevin Hartz.

You likely know, too, that brash entrepreneur Chamath Palihapitiya seemed to kick off the craze around SPACs — blank-check companies that are formed for the purpose of merging or acquiring other companies — in 2017 when he raised $600 million for a SPAC. Called Social Capital Hedosophia Holdings, it was ultimately used to take a 49% stake in the British spaceflight company Virgin Galactic.

But how do SPACs come together in the first place, how do they work exactly, and should you be thinking of launching one? We talked this week with a number of people who are right now focused on almost nothing but SPACs to get our questions — and maybe yours, too — answered.

Why are SPACs suddenly sprouting up everywhere?

Kevin Hartz — who we spoke with after his $200 million blank-check company made its stock market debut on Tuesday — said their popularity ties in part to “Sarbanes Oxley and the difficulty in taking a company public the traditional route.”

Troy Steckenrider, an operator who has partnered with Hartz on his newly public company, said the growing popularity of SPACs also ties to a “shift in the quality of the sponsor teams,” meaning that more people like Hartz are shepherding these vehicles versus “people who might not be able to raise a traditional fund historically.”

Don’t forget, too, that there are whole lot of companies that have raised tens and hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital and whose IPO plans may have been derailed or slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some need a relatively frictionless way to get out the door, and there are plenty of investors who would like to give them that push.

How does one start the process of creating a SPAC?

The process is really no different than a traditional IPO, explains Chris Weekes, a managing director in the capital markets group at the investment bank Cowen. “There’s a roadshow that will incorporate one-on-one meetings between institutional investors like hedge funds and private equity funds and the SPAC’s management team” to drum up interest in the offering.

At the end of it, institutional investors, which also right now include a lot of family offices, buy into the offering, along with a smaller percentage of retail investors.

Who can form a SPAC?

Pretty much anyone who can persuade shareholders to buy its shares.

What happens right after SPAC has raised its capital?

The money is moved into a blind trust until the management team decides which company or companies it wants to acquire. Share prices don’t really move much during this period as no investors know (or should know, at least) what the target company will be yet.

These SPACs all seem to sell their shares at $10 apiece. Why?

Easier accounting? Tradition? It’s not entirely clear, though Weekes says $10 has “always been the unit price” for SPACs and continues to be with the very occasional exception, such as with hedge fund billionaire Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square Capital Management. (Last month it launched a $4 billion SPAC that sold units for $20 each.)

Have SPACs changed structurally over the years?

They have! Years back, when a SPAC told its institutional investors (under NDA) about the company it had settled on buying, these investors would either vote ‘yes’ to the deal if they wanted to keep their money in, or ‘no’ if they wanted to redeem their shares and get out. But sometimes investors would team up and threaten to torpedo a deal if they weren’t given founder shares or other preferential treatment in what was to become the newly combined company. (“There was a bit of bullying in the marketplace,” says Weekes.)

Regulators have since separated the right to vote and the right to redeem one’s shares, meaning investors today can vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and still redeem their capital, making the voting process more perfunctory and enabling most deals to go through as planned.

I’ve read something about warrants.

That’s because when buying a unit of a SPAC, institutional investors typically get a share of common stock, plus a warrant or a fraction of a warrant, which is a security that entitles the holder to buy more stock of the issuing company at a fixed price at a later date. It’s basically an added sweetener to motivate them to buy into the SPAC.

Are SPACs safer investments than they once were? They haven’t had the best reputation historically.

They’ve “already gone through their junk phase,” suspects Albert Vanderlaan, an attorney in the tech companies group of Orrick, the global law firm. “In the ’90s, these were considered a pretty junky situation,” he says. “They were abused by foreign investors. In the early 2000s, they were still pretty disfavored.” Things could turn on a dime again, he suggests, but over the last couple of years, the players have changed for the better, which is making a big difference.

How much of the money raised does a management team like Hartz and Steckenrider keep?

The rough rule of thumb is 2% of the SPAC value, plus $2 million, says Steckenrider. The 2% roughly covers the initial underwriting fee; the $2 million then covers the operating expenses of the SPAC, from the initial cost to launch it, to legal preparation, accounting, and NYSE or NASDAQ filing fees. It also “provides the reserves for the ongoing due diligence process,” he says.

Is this money like the carry that VCs receive, and do a SPAC’s managers receive it no matter how the SPAC performs?

Yes and yes.

Here’s how Hartz explains it: “On a $200 million SPAC, there’s a $50 million ‘promote’ that is earned.” But “if that company doesn’t perform and, say, drops in half over a year or 18-month period, then the shares are still worth $25 million.”

Hartz calls this “egregious,” though he and Steckenrider formed their SPAC in exactly the same way rather than structure it differently.

Says Steckrider, “We ultimately decided to go with a plain-vanilla structure [because] as a first-time SPAC sponsor, we wanted to make sure that the investment community had as easy as a time as possible understanding our SPAC. We do expect to renegotiate these economics when we go and do the [merger] transaction with the partner company,” he adds.

Does a $200 million SPAC look to acquire a company that’s valued at around the same amount?

No. According to law firm Vinson & Elkins, there’s no maximum size of a target company — only a minimum size (roughly 80% of the funds in the SPAC trust).

In fact, it’s typical for a SPAC to combine with a company that’s two to four times its IPO proceeds in order to reduce the dilutive impact of the founder shares and warrants.

In the case of Hartz’s and Steckenrider’s SPAC (it’s called “one”), they are looking to find a company “that’s approximately four to six times the size of our vehicle of $200 million,” says Hartz, “so that puts us around in the billion dollar range.”

Where does the rest of the money come from if the partner company is many times larger than the SPAC itself?

It comes from PIPE deals, which, like SPACs, have been around forever and come into and out of fashion. These are literally “private investments in public equities” and they get tacked onto SPACs once management has decided on the company with which it wants to merge.

It’s here that institutional investors get different treatment than retail investors, which is why some industry observers are wary of SPACs.

Specifically, a SPAC’s institutional investors — along with maybe new institutional investors that aren’t part of the SPAC — are told before the rest of the world what the acquisition target is under confidentiality agreements so that they can decide if they want to provide further financing for the deal via a PIPE transaction.

The information asymmetry seems unfair. Then again, they’re restricted not only from sharing information but also from trading the shares for a minimum of four months from the time that the initial business combination is made public. Retail investors, who’ve been left in the dark, can trade their shares any time.

How long does a SPAC have to get all of this done?

It varies, but the standard is around two years.

And if they can’t get it done in the designated time frame?

The money goes back to shareholders.

What do you call that phase of the deal after the partner company has been identified and agrees to merge, but before the actual combination?

That’s called the de-SPAC’ing process, and during this stage of things, the SPAC has to obtain shareholder approval, followed by a review and commenting period by the SEC.

Toward the end of this stretch — which can take 12 to 18 weeks altogether — bankers start taking out the new operating team in the style of a traditional roadshow and getting the story out to analysts who cover the industry so that when the combined new company is revealed, it receives the kind of support that keeps public shareholders interested in a company.

Will we see more people from the venture world like Palihapitiya and Hartz start SPACs?

Weekes, the investment banker, says he’s seeing less interest from VCs in sponsoring SPACs and more interest from them in selling their portfolio companies to a SPAC. As he notes, “Most venture firms are typically a little earlier stage investors and are private market investors, but there’s an uptick of interest across the board, from PE firms, hedge funds, long-only mutual funds.”

That might change if Hartz has anything to do with it. “We’re actually out in the Valley, speaking with all the funds and just looking to educate the venture funds,” he says. “We’ve had a lot of requests in. We think we’re going to convert [famed VC] Bill Gurley from being a direct listings champion to the SPAC champion very soon.”

In the meantime, asked if his SPAC has a specific target in mind already, Hartz says it does not. He also takes issue with the word “target.”

Says Hartz, “We prefer ‘partner company.’” A target, he adds, “sounds like we’re trying to assassinate somebody.”

Powered by WPeMatico

You’d be hard pressed to hang out with a designer and not hear the name Figma .

The company behind the largely browser-based design tool has made a huge splash in the past few years, building a massive war chest with more than $130 million from investors like A16Z, Sequoia, Greylock, Kleiner Perkins and Index.

The company was founded in 2012 and spent several years in stealth, raising both its seed and Series A without having any public product or user metrics.

At Early Stage, we spoke with co-founder and CEO Dylan Field about the process of hiring and fundraising while in stealth and how life at the company changed following its launch in 2016. Field, who was 20 when he founded the company, also touched on the lessons he’s learned from his team about leadership. Chief among them: the importance of empowering the people you hire.

You can check out the full conversation in the video embedded below, as well as a lightly edited transcript.

I actually had approached John Lilly from Greylock in our seed round. For those who don’t know, John Lilly was the CEO of Mozilla and an amazing guy. He’s on a lot of really cool boards and has a bunch of interesting experience for Figma, with very deep roots in design. I had approached him for the seed round, and he basically said to us, “You know, I don’t think you guys know what you’re doing, but I’m very intrigued, so let’s keep in touch.” This is the famous line that you hear from every investor ever. It’s like “Yeah, let’s keep in touch, let me know if I can be helpful.” Sometimes, they actually mean it. In John’s case, he actually would follow up every few months or I would follow up with him. We’d grab coffee, and he helped me develop the strategy to a point that got us to what we are today. And that was a collaboration. I could really learn a lot from him on that one.

When we started off the idea was: Let’s have this global community around design, and you’ll be able to use the tool to post to the community and someday we’ll think about how people can pay us. Talking with John got me to the point where I realized we need to start with a business tool. We’ll build the community later. Now, we’re starting to work toward that.

At some point, John told me, “Hey, if you ever think about raising again, let me know.” A few weeks later, I told him maybe we would raise because I just wanted to work with him. We talked to a few other investors. I think it’s pretty important that there’s always a competitive dynamic in the round. But really, it was just him that we were really considering for that round. He really did us a solid. He really believed in us. At the time, it wasn’t like there were metrics to look at. He had conviction in the space, a conviction in the attack, and he had conviction in me and Evan, which I feel very, very honored by. He’s a dear mentor to this day, and he’s on our board. And it’s been a really deep relationship.

Powered by WPeMatico

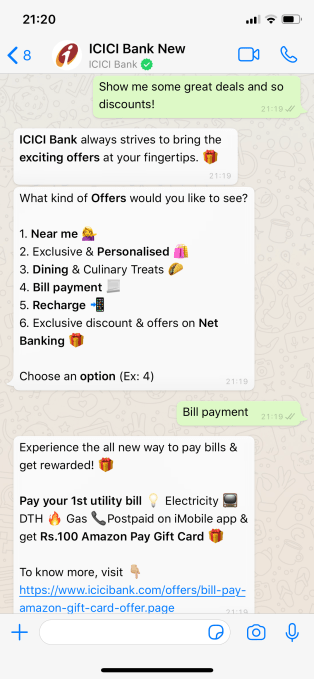

Yalochat, a five-year-old, Mexico City-based conversational commerce platform that enables customers like Coca-Cola and Walmart to upsell, collect payments and provide better service to their own customers over WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger and WeChat in China, has closed on $15 million in Series B funding led by B Capital Group.

Sierra Ventures, which led a $10 million Series A financing for the company in early 2019, also participated.

The round isn’t so surprising if Yalochat’s numbers are to be believed. It says that since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, its platform has seen a tenfold increase in volume, and a 650% increase of message volume as more large enterprises — especially outside of the U.S. — use messaging apps to manage some of their sales operations and much of their customer service.

Yalochat is chasing a fast-growing market, too. According to the 10-year-old, India-based market research company MarketsandMarkets, the conversational AI software market should see $4.8 billion in revenue this year and more than triple that amount by 2025.

Certainly, having conglomerates on board is speeding along the company’s growth.

“With Coca-Cola, we started in Brazil and we helped them run their commerce when it comes to talking with small mom-and-pop shops,” says Yalochat founder and CEO Javier Mata, a Columbia University grad who studied engineering and founded three other companies beginning in 2013 before launching Yalochat.

“They had such success running their ordering process that they then took us to Mexico and Colombia, and we’re talking with [them about entering into the] Philippines and India.” Says Mata, “You try to get fast success in one market, then the conglomerate takes you into other areas of business so they can optimize their workflows around sales and customer service in other countries.”

Mata makes the process sound awfully easy, particularly considering that dozens of startups are also focused on conversational commerce and also raising funding right now.

Still, he argues that if you build your product the right way, it becomes a no-brainer for customers.

In pitching companies like Walmart, for example, he says Yalochat would “start with something super simple but high value that they could launch in a week. We’d say, ‘That process for sales that it has taken you years [to organize], we can get it out for you by Friday.’ Then we’d just do it.

“It was low stakes for them to try us out, and as soon as they saw our conversion rates, we were introduced to other [units] with the corporation.” Says Mata, “I think why a lot of other companies haven’t been successful is that [their tech] is not simple or doesn’t really work. We made ours scalable, easy to launch and capable of running smoothly without passing that complexity to end users.”

B Capital is plainly buying what Yalochat is selling. Firm co-founder Eduardo Saverin — who famously co-founded Facebook — calls Mata and his team “phenomenally strong” and suggests there’s little to stop their trajectory right now. “Yalo is an example of a Latin American business that is already today in Asia. And if you’re building a conversational commerce enablement for large enterprises that redefines the way they touch customers — [meaning] messaging applications, the most engaging medium in the world today — should that really be confined to Latin America or Asia? Absolutely not.”

Saverin compares the startup to B Capital itself, which has offices in LA, San Francisco, New York and Singapore.

The firm has already made bets in the U.S., Europe and Asia, since getting off the ground in 2015. Now, with Yalo, it has its first investment that’s principally headquartered in Latin America, as well. “For us,” says Saverin, who grew up in Brazil, “we didn’t start investing everywhere on day one. But that’s the mission.”

Powered by WPeMatico

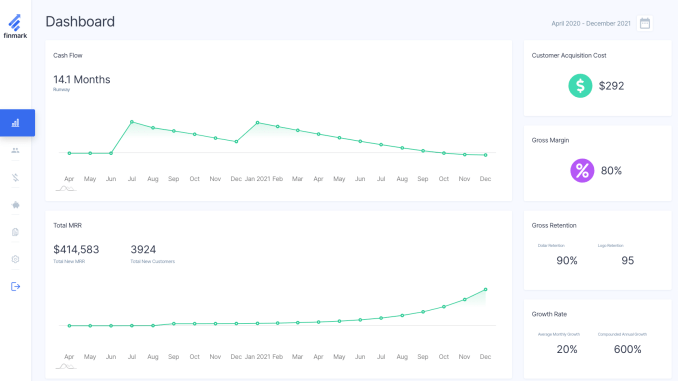

Finmark, a member of the Summer 2020 Y Combinator cohort, is not your typical YC startup. In fact company co-founder Rami Essaid has already built Distil, a security startup, and saw it through to exit when he sold the company to Imperva last year.

As he pondered what to do next, he took a quick turn at InsightFinder before turning his attention to a problem every startup founder faces: modeling what your financial future could look like. “Finmark is financial modeling for startups. We want to help founders understand their runway, their cash flow, their hiring plans and be able to do it in an easy way,” Essaid told TechCrunch.

It’s a problem he saw firsthand when he was co-founder at Distil. Like most startups, these projections were kind of a crapshoot in Excel. He wants to make it more precise and easy to get the big picture of your company’s finances before you can afford more sophisticated financial tracking software.

“One of the biggest pain points was always understanding where our projections were relative to what we were actually doing as a company. So many times we were running our entire business off of Excel, and so many times the forecasts of what we thought we were going to do were wrong,” he said.

He says it’s tough enough, even after you hire your first CFO and have professional rigor applied to your projections. As he sees it, the problem is you’re always looking back and always playing catchup. What’s more, because it’s done manually in Excel, he says that it introduces a lot of room for error.

Image Credits: Finmark

He admits this isn’t exactly a new idea. Companies like Anaplan and Adaptive Insights have been able to move modeling like this beyond Excel, but up until now he says that these tools have been designed for large enterprises, and he wanted to come up with a tool within reach of anyone, regardless of their size.

If you think it’s too limited a market, Essaid doesn’t agree. He sees a need and he thinks he can turn early-stage startups into paying customers, who eventually will pay significant money to have a tool like this to help them manage all of their finances in a professional manner. One way to build his customer base could be to partner with early-stage venture capitalists, whose portfolio companies could benefit from a service like this, an avenue he intends to pursue.

So why does an experienced entrepreneur join Y Combinator? Essaid candidly says that he saw the program as a good way to market the product. YC companies are his prime target audience. “Even as a repeat founder with some gray hair, I thought access to the network alone was worth the equity of YC,” he said.

But beyond the practical aspects, he says he still has plenty to learn. “Even with all of the lessons that I have learned, you don’t know everything, and they see a lot more companies than the ones that I’ve had a chance to operate, so I still find nuggets of wisdom in going through the program,” he said.

While Essaid has a company under his belt, which dedicated hundreds of thousands of dollars to scholarships for women in STEM, he admits that it’s hard to build a diverse organization and it’s something he’s still working on. He co-founded the company with two ex-Distil engineers, and he says there is a natural inclination to go back to the people he worked with before at Distil as he adds early employees, but he recognizes that he will not necessarily grow a diverse group of employees that way.

“I don’t have an answer to solving it yet. [ … ] We’ve been hiring from ex-Distilers but once we look outside of that, I think it’s really important to set up things in a way where you can look [ … ] at resumes with an unbiased lens,” he said.

For now, with 15 employees on the payroll, he’s just trying to build the company. He hinted that he is working on obtaining funding, but didn’t have anything definitive to say just yet.

Powered by WPeMatico

Dutchie, a nearly three-year-old, Bend, Oregon-based software company focused on connecting consumers with cannabis dispensaries that pay it a monthly subscription fee to create and maintain their websites, process their orders and track what needs to be ready for pickup, has raised $35 million in Series B funding. The capital came both new investors Thrive Capital and Starbucks founder Howard Schultz, along with earlier backers, including Kevin Durant’s Thirty Five Ventures and the cannabis-focused fund Casa Verde Capital.

The money comes hot on the heels of Dutchie’s first major round of funding — $15 million that it closed last September — and suggests that the cannabis industry has fared better during the COVID-19 pandemic than people outside the industry might imagine.

We had a fast chat yesterday with the company’s co-founder and CEO, Ross Lipson, about the year that Dutchie is having.

TC: I’d seen recently that Dutchie has added contactless payments.

RL: Yes, when the pandemic hit, virtually all of our dispensaries shifted to a curbside pickup model. We built a solution that allows customers to select curbside at checkout, and also includes a way to notify the dispensary when they arrive and provides them information on how to locate their vehicle.

TC: A year ago, there were more than 30 states where cannabis was either medically legal or that had legalized the recreational use of marijuana. How has that changed?

RL: We now work with over 1,300 dispensaries in 32 markets. By comparison, a year ago we were only operating in 9 markets. Nationwide, 47 out of 50 states now allow some form of legal cannabis, and 2020 could bring full legalization in major markets such as New Jersey and Arizona.

TC. Can you put that into context? How many dispensaries are there in the U.S.?

RL: Dutchie processes 10% of all legal cannabis sales worldwide and powers over 25% of dispensaries. That’s more than 75,000 orders a day.

TC: You had 36 employees the last time we talked. What’s that number now?

RL: We currently have 102 employees and we aim to double our team by the end of 2021.

TC: Aside from helping dispensaries shift to a curbside model, how has the pandemic impacted your business?

RL: Virtually all states deemed cannabis dispensaries as essential businesses [once COVID took hold]. Many still had to comply with state laws and close their physical stores, though, leaving only one option for sales — online ordering. We saw dispensaries shift from about 30% of overall sales coming from Dutchie to upwards of 100%, and our business grew 600% in roughly one month.

Overall, we’ve seen a 700% surge in sales volume during the pandemic. We had to scale quickly to deal with six times the load on our technology.

TC: Think those numbers will shift around as some parts of the country open up?

RL: Dispensaries are poised to keep online ordering and e-commerce options available because it is part of what their customers now expect.

Pictured, left to right, above: Ross and Zach Lipson (Zach, Ross’s brother, is the company’s co-founder and chief product officer).

Powered by WPeMatico

Movable Ink, a company that helps businesses deliver more personalized and relevant email marketing, is announcing that it has raised $30 million in Series C funding.

The company will be 10 years old in October, and founder and CEO Vivek Sharma told me that it’s always been “capital efficient” — even with the new round, Movable Ink has only raised a total of $39 million.

However, Sharma noted that with COVID-19, it felt like “a good idea to have some dry powder on our balance sheet … if things turned south.”

At the same time, he suggested that the pandemic’s impact has been more limited than he anticipated, and has been “really focused” on a few sectors like travel, hospitality and “old line retailers.”

“Those who are adopting to e-commerce really quickly have done well, financial services has done well, media has done well,” he said.

The company’s senior vice president of strategy Alison Lindland added that clients using Movable Ink were able to move much more quickly, with campaigns that would normally take months launching in just a few days.

“We really saw those huge, wholesale digital transformations in a time of duress,” Lindland said. “Obviously, large Fortune 500 companies were making difficult decisions, were putting vendors on hold, but email marketers are always the last people furloughed themselves, because of how critical email marketing is to their businesses. We were just as critical to their operations.”

Image Credits: Movable Ink

The company said it now works with more than 700 brands, and in the run up to the 2020 election, its customers include the Democratic National Committee.

The new funding comes from Contour Venture Partners, Intel Capital and Silver Lake Waterman. Sharma said the money will be spent on three broad categories: “Platforms, partners and people.”

On the platform side, that means continuing to develop Movable Ink’s technology and expanding into new channels. He estimated that around 95% of Movable Ink’s revenue comes from email marketing, but he sees a big opportunity to grow the web and mobile side of the business.

“We take any data the brand has available to it and activate and translate it into really engaging creative,” he said, arguing that this approach is applicable in “every other channel where there’s pixels in front of the consumer’s eyes.”

The company also plans to make major investments into AI. Sharma said it’s too early to share details about those plans, but he pointed to the recent hire of Ashutosh Malaviya as the company’s vice president of artificial intelligence.

As for partners, the company has launched the Movable Ink Exchange, a marketplace for integrations with data partners like Oracle Commerce Cloud, MessageGears Engage, Trustpilot and Yopto.

And Movable Ink plans to expand its team, both through hiring and potential acquisitions. To that end, it has hired Katy Huber as its senior vice president of people.

Sharma also said that in light of the recent conversations about racial justice and diversity, the company has been looking at its own hiring practices and putting more formal measures in place to track its progress.

“We use OKRs to track other areas of the business, so if we don’t incorporate [diversity] into our business objectives, we’re only paying lip service,” he said. “For us, it was really important to not just have a big spike of interest, and instead save some of that energy so that it’s sustained into the future.”

Powered by WPeMatico