funding

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Fivetran, a startup that builds automated data pipelines between data repositories and cloud data warehouses and analytics tools, announced a $15 million Series A investment led by Matrix Partners.

Fivetran helps move data from source repositories like Salesforce and NetSuite to data warehouses like Snowflake or analytics tools like Looker. Company CEO and co-founder George Fraser says the automation is the key differentiator here between his company and competitors like Informatica and SnapLogic.

“What makes Fivetran different is that it’s an automated data pipeline to basically connect all your sources. You can access your data warehouse, and all of the data just appears and gets kept updated automatically,” Fraser explained. While he acknowledges that there is a great deal of complexity behind the scenes to drive that automation, he stresses that his company is hiding that complexity from the customer.

The company launched out of Y Combinator in 2012, and other than $4 million in seed funding along the way, it has relied solely on revenue up until now. That’s a rather refreshing approach to running an enterprise startup, which typically requires piles of cash to build out sales and marketing organizations to compete with the big guys they are trying to unseat.

One of the key reasons they’ve been able to take this approach has been the company’s partner strategy. Having the ability to get data into another company’s solution with a minimum of fuss and expense has attracted data-hungry applications. In addition to the previously mentioned Snowflake and Looker, the company counts Google BigQuery, Microsoft Azure, Amazon Redshift, Tableau, Periscope Data, Salesforce, NetSuite and PostgreSQL as partners.

Ilya Sukhar, general partner at Matrix Partners, who will be joining the Fivetran board under the terms of deal sees a lot of potential here. “We’ve gone from companies talking about the move to the cloud to preparing to execute their plans, and the most sophisticated are making Fivetran, along with cloud data warehouses and modern analysis tools, the backbone of their analytical infrastructure,” Sukhar said in a statement.

They currently have 100 employees spread out across four offices in Oakland, Denver, Bangalore and Dublin. They boast 500 customers using their product including Square, WeWork, Vice Media and Lime Scooters, among others.

Powered by WPeMatico

It’s been a whirlwind few months for Forethought, a startup with a new way of looking at enterprise search that relies on artificial intelligence. In September, the company took home the TechCrunch Disrupt Battlefield trophy in San Francisco, and today it announced a $9 million Series A investment.

It’s pretty easy to connect the dots between the two events. CEO and co-founder Deon Nicholas said they’ve seen a strong uptick in interest since the win. “Thanks to TechCrunch Disrupt, we have had a lot of things going on including a bunch of new customer interest, but the biggest news is that we’ve raised our $9 million Series A round,” he told TechCrunch.

The investment was led by NEA with K9 Ventures, Village Global and several angel investors also participating. The angel crew includes Front CEO Mathilde Collin, Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev and Learnvest CEO Alexa von Tobel.

Forethought aims to change conventional enterprise search by shifting from the old keyword kind of approach to using artificial intelligence underpinnings to retrieve the correct information from a corpus of documents.

“We don’t work on keywords. You can ask questions without keywords and using synonyms to help understand what you actually mean, we can actually pull out the correct answer [from the content] and deliver it to you,” Nicholas told TechCrunch in September.

He points out that it’s still early days for the company. It had been in stealth for a year before launching at TechCrunch Disrupt in September. Since the event, the three co-founders have brought on six additional employees and they will be looking to hire more in the next year, especially around machine learning and product and UX design.

At launch, they could be embedded in Salesforce and Zendesk, but are looking to expand beyond that.

The company is concentrating on customer service for starters, but with the new money in hand, it intends to begin looking at other areas in the enterprise that could benefit from a smart information retrieval system. “We believe that this can expand beyond customer support to general information retrieval in the enterprise,” Nicholas said.

Powered by WPeMatico

Chewse, a food catering and company culture startup, just announced a $19 million fundraising round as it gears up to expand its operations in the Silicon Valley area. This brings Chewse’s total funding to more than $30 million. Chewse’s investors include Foundry Group, 500 Startups and Gingerbread Capital.

Instead of plopping down meals in the office and bouncing, Chewse aims to create a full experience for its customers by offering family-style meals. In order to ensure quality, Chewse employs drivers and meal hosts so that it can provide them with training. Chewse also offers it drivers and meal hosts benefits.

“We initially started with a contractor model but then very quickly started to realize our customers often mentioned the host or the driver in their feedback,” Chewse CEO and co-founder Tracy Lawrence told TechCrunch.

“I know there’s a lot of other companies that are like food tech or logistics but for us, it’s all about elevating and improving company culture,” Lawrence said. “We have technology but we’re investing in it to create an exceptional real-life experience.”

“On the tech side, we’re using a ton of machine learning and algorithms to learn what people like to eat and create custom meal schedules,” Lawrence said.

To date, Chewse has hundreds of customers across three markets. Chewse initially launched in Los Angeles, but paused operations for a little over one year in order to focus on achieving market profitability in San Francisco. Chewse has since relaunched in Los Angeles, in addition to launching in cities like Palo Alto and San Jose. As part of the Silicon Valley launch, Chewse has partnered with restaurants like Smoking Pig, HOM Korean Kitchen and Oren’s Hummus Shop.

Within the next year, the goal is to double the number of markets where Chewse operates. But Chewse faces tough competition in the corporate meal catering space.

Earlier this year, Square acquired Zesty to become part of its food delivery service, Caviar. The aim of the acquisition was to strengthen Caviar’s corporate food ordering business, Caviar for Teams.

At the time, Zesty counted about 150 restaurant customers in San Francisco, which is the only city in which it operates. Some of Zesty’s customers include Snap, Splunk and TechCrunch. Zesty, which first launched in 2013 under a different name, had previously raised $20.7 million in venture funding.

“Zesty is a direct competitor of ours for sure,” Lawrence said. “When we’re thinking about the things that set us apart from Zesty and ZeroCater, the investment in using the technology and building a meal algorithm — which is something we know they’re doing by hand — and then automatically calibrate when we’re getting feedback because we employ our hosts and our drivers. Yes, it’s more expensive for us but because it provides such a superior experience, we retain our customer longer.”

Powered by WPeMatico

In order to have innovative smart city applications, cities first need to build out the connected infrastructure, which can be a costly, lengthy, and politicized process. Third-parties are helping build infrastructure at no cost to cities by paying for projects entirely through advertising placements on the new equipment. I try to dig into the economics of ad-funded smart city projects to better understand what types of infrastructure can be built under an ad-funded model, the benefits the strategy provides to cities, and the non-obvious costs cities have to consider.

Consider this an ongoing discussion about Urban Tech, its intersection with regulation, issues of public service, and other complexities that people have full PHDs on. I’m just a bitter, born-and-bred New Yorker trying to figure out why I’ve been stuck in between subway stops for the last 15 minutes, so please reach out with your take on any of these thoughts: @Arman.Tabatabai@techcrunch.com.

When we talk about “Smart Cities”, we tend to focus on these long-term utopian visions of perfectly clean, efficient, IoT-connected cities that adjust to our environment, our movements, and our every desire. Anyone who spent hours waiting for transit the last time the weather turned south can tell you that we’ve got a long way to go.

But before cities can have the snazzy applications that do things like adjust infrastructure based on real-time conditions, cities first need to build out the platform and technology-base that applications can be built on, as McKinsey’s Global Institute explained in an in-depth report released earlier this summer. This means building out the network of sensors, connected devices and infrastructure needed to track city data.

However, reaching the technological base needed for data gathering and smart communication means building out hard physical infrastructure, which can cost cities a ton and can take forever when dealing with politics and government processes.

Many cities are also dealing with well-documented infrastructure crises. And with limited budgets, local governments need to spend public funds on important things like roads, schools, healthcare and nonsensical sports stadiums which are pretty much never profitable for cities (I’m a huge fan of baseball but I’m not a fan of how we fund stadiums here in the states).

As city infrastructure has become increasingly tech-enabled and digitized, an interesting financing solution has opened up in which smart city infrastructure projects are built by third-parties at no cost to the city and are instead paid for entirely through digital advertising placed on the new infrastructure.

I know – the idea of a city built on ad-revenue brings back soul-sucking Orwellian images of corporate overlords and logo-paved streets straight out of Blade Runner or Wall-E. Luckily for us, based on our discussions with developers of ad-funded smart city projects, it seems clear that the economics of an ad-funded model only really work for certain types of hard infrastructure with specific attributes – meaning we may be spared from fire hydrants brought to us by Mountain Dew.

While many factors influence the viability of a project, smart infrastructure projects seem to need two attributes in particular for an ad-funded model to make sense. First, the infrastructure has to be something that citizens will engage – and engage a lot – with. You can’t throw a screen onto any object and expect that people will interact with it for more than 3 seconds or that brands will be willing to pay to throw their taglines on it. The infrastructure has to support effective advertising.

Second, the investment has to be cost-effective, meaning the infrastructure can only cost so much. A third-party that’s willing to build the infrastructure has to believe they have a realistic chance of generating enough ad-revenue to cover the costs of the projects, and likely an amount above that which could lead to a reasonable return. For example, it seems unlikely you’d find someone willing to build a new bridge, front all the costs, and try to fund it through ad-revenue.

A LinkNYC kiosk enabling access to the internet in New York on Saturday, February 20, 2016. Over 7500 kiosks are to be installed replacing stand alone pay phone kiosks providing free wi-fi, internet access via a touch screen, phone charging and free phone calls. The system is to be supported by advertising running on the sides of the kiosks. ( Richard B. Levine) (Photo by Richard Levine/Corbis via Getty Images)

To get a better understanding of the types of smart city hardware that might actually make sense for an ad-funded model, we can look at the engagement levels and cost structures of smart kiosks, and in particular, the LinkNYC project. Smart kiosks – which provide free WiFi, connectivity and real-time services to citizens – have been leading examples of ad-funded smart city projects. Innovative companies like Intersection (developers of the LinkNYC project), SmartLink, IKE, Soofa, and others have been helping cities build out kiosk networks at little-to-no cost to local governments.

LinkNYC provides public access to much of its data on the New York City Open-Data website. Using some back-of-the-envelope math and a hefty number of assumptions, we can try to get to a very rough range of where cost and engagement metrics generally have to fall for an ad-funded model to make sense.

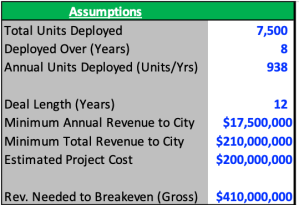

To try and retrace considerations for the developers’ investment decision, let’s first look at the terms of the deal signed with New York back in 2014. The agreement called for a 12-year franchise period, during which at least 7,500 Link kiosks would be deployed across the city in the first eight years at an expected project cost of more than $200 million. As part of its solicitation, the city also required the developers to pay the greater of either a minimum annual payment of at least $17.5 million or 50 percent of gross revenues.

Let’s start with the cost side – based on an estimated project cost of around $200 million for at least 7,500 Links, we can get to an estimated cost per unit of $25,000 – $30,000. It’s important to note that this only accounts for the install costs, as we don’t have data around the other cost buckets that the developers would also be on the hook for, such as maintenance, utility and financing costs.

Source: LinkNYC, NYC.gov, NYCOpenData

Turning to engagement and ad-revenue – let’s assume that the developers signed the deal with the expectations that they could at least breakeven – covering the install costs of the project and minimum payments to the city. And for simplicity, let’s assume that the 7,500 links were going to be deployed at a steady pace of 937-938 units per year (though in actuality the install cadence has been different). In order for the project to breakeven over the 12-year deal period, developers would have to believe each kiosk could generate around $6,400 in annual ad-revenue (undiscounted).

Source: LinkNYC, NYC.gov, NYCOpenData

The reason the kiosks can generate this revenue (and in reality a lot more) is because they have significant engagement from users. There are currently around 1,750 Links currently deployed across New York. As of November 18th, LinkNYC had over 720,000 weekly subscribers or around 410 weekly subscribers per Link. The kiosks also saw an average of 18 million sessions per week, or 20-25 weekly sessions per subscriber, or around 10,200 weekly sessions per kiosk (seasonality might even make this estimate too low).

And when citizens do use the kiosks, they use it for a long time! The average session for each Link unit was four minutes and six seconds. The level of engagement makes sense since city-dwellers use these kiosks in time or attention-intensive ways, such making phone calls, getting directions, finding information about the city, or charging their phones.

The analysis here isn’t perfect, but now we at least have a (very) rough idea of how much smart kiosks cost, how much engagement they see, and the amount of ad-revenue developers would have to believe they could realize at each unit in order to ultimately move forward with deployment. We can use these metrics to help identify what types of infrastructure have similar profiles and where an ad-funded project may make sense.

Bus stations, for example, may cost about $10,000 – $15,000, which is in a similar cost range as smart kiosks. According to the MTA, the NYC bus system sees over 11.2 million riders per week or nearly 700 riders per station per week. Rider wait times can often be five-to-ten minutes in length if not longer. Not to mention bus stations already have experience utilizing advertising to a certain degree. Projects like bike-share docking stations and EV charging stations also seem to fit similar cost profiles while having high engagement.

And interactions with these types of infrastructure are ones where users may be more receptive to ads, such as an EV charging station where someone is both physically engaging with the equipment and idly looking to kill up sometimes up to 30 minutes of time as they charge up. As a result, more companies are using advertising models to fund projects that fit this mold, like Volta, who uses advertising to offer charging stations free to citizens.

When it makes sense for cities and third-party developers, advertising-funded smart city infrastructure projects can unlock a tremendous amount of value for a city. The benefits are clear – cities pay nothing, citizens are offered free connectivity and real-time information on local conditions, and smart infrastructure is built and can possibly be used for other smart city applications down the road, such as using locational data tracking to improve city zoning and congestion.

Yes, ads are usually annoying – but maybe understanding that advertising models only work for specific types of smart city projects may help quell fears that future cities will be covered inch-to-inch in mascots. And ads on projects like LinkNYC promote local businesses and can tap into idiosyncratic conditions and preferences of regional communities – LinkNYC previously used real-time local transit data to display beer ads to subway riders that were facing heavy delays and were probably in need of a drink.

Like everyone’s family photos from Thanksgiving, the picture here is not all roses, however, and there are a lot of deep-rooted issues that exist under the surface. Third-party developed, advertising-funded infrastructure comes with externalities and less obvious costs that have been fairly criticized and debated at length.

When infrastructure funding is derived from advertising, concerns arise over whether services will be provided equitably across communities. Many fear that low-income or less-trafficked communities that generate less advertising demand could end up having poor infrastructure and maintenance.

Even bigger points of contention as of late have been issues around data consent and treatment. I won’t go into much detail on the issue since it’s incredibly complex and warrants its own lengthy dissertation (and many have already been written).

But some of the major uncertainties and questions cities are trying to answer include: If third-parties pay for, manage and operate smart city projects, who should own data on citizens’ living behavior? How will citizens give consent to provide data when tracking systems are built into the environment around them? How can the data be used? How granular can the data get? How can we assure citizens’ information is secure, especially given the spotty track records some of the major backers of smart city projects have when it comes to keeping our data safe?

The issue of data treatment is one that no one has really figured out yet and many developers are doing their best to work with cities and users to find a reasonable solution. For example, LinkNYC is currently limited by the city in the types of data they can collect. Outside of email addresses, LinkNYC doesn’t ask for or collect personal information and doesn’t sell or share personal data without a court order. The project owners also make much of its collected data publicly accessible online and through annually published transparency reports. As Intersection has deployed similar smart kiosks across new cities, the company has been willing to work through slower launches and pilot programs to create more comfortable policies for local governments.

But consequential decisions related to third-party owned smart infrastructure are only going to become more frequent as cities become increasingly digitized and connected. By having third-parties pay for projects through advertising revenue or otherwise, city budgets can be focused on other vital public services while still building the efficient, adaptive and innovative infrastructure that can help solve some of the largest problems facing civil society. But if that means giving up full control of city infrastructure and information, cities and citizens have to consider whether the benefits are worth the tradeoffs that could come with them. There is a clear price to pay here, even when someone else is footing the bill.

Powered by WPeMatico

Asana, a service that teams and individuals use to plan and track the progress of work projects, is doubling down on its own project: to shape “the future of work,” in the words of co-founder and CEO Dustin Moskovitz. The startup, whose products are used by millions of free and paying users, today is announcing that it has raised another $50 million in funding — a Series E that catapults Asana into unicorn status with a $1.5 billion valuation — to invest in international and product expansion.

Asana has been on a funding tear: It raised $75 million just 11 months ago at a $900 million post-money valuation, bringing the total this year to $125 million, and $213 million since being founded in 2008.

Led by Generation Investment Management — the London firm co-founded by former US Vice President Al Gore that also led that Series D in January — this latest round also includes existing investors 8VC, Benchmark Capital and Founders Fund as well as new investors Lead Edge Capital and World Innovation Lab.

Asana has lately been focused on international growth — half of its new sales are already coming from outside the US — and expanding its product as it inches toward profitability. These are the areas where its latest investment will go, too.

Specifically, it plans to open an AWS-based data center in Frankfurt in the first half of next year, and it will set down more roots in Asia-Pacific, with offices in Sydney and Tokyo. It is also hiring in both markets. Asana has customers in 195 countries and six languages, and it looks like it’s homing in on these two regions because it’s seeing the most traction there.

On the product side, the company has been gradually adding machine learning, predictive and other AI features and it will continue to do that as part of a “long-term vision for marrying computer and human intelligence to run entire companies.”

“Our role is to help leaders understand where their attention can be most useful and what to be focused on,” Moskovitz, pictured right with co-founder Justin Rosenstein, said to me in an interview earlier this month when describing the company’s AI push.

The funding caps off an active year for Asana.

In addition to raising $75 million in January, it announced 50,000 paying organizations and “millions” of free users in September. It also introduced new products and features, such as a paid tier, Asana for Business, for larger organizations managing multiple projects; Timelines for drilling into sequential tasks and milestones; and its first steps into AI, services that start to anticipate what users need to see first and prioritise, based on previous behaviour, which team the user is on, and so on:

Asana has been close to profitability this year, although it doesn’t look like it has quite reached that point yet. Moskovitz told me that in fact, it has held on to most of its previous funding (that’s before embarking on this next wave of ambitious expansions, though).

“We have so much money in the bank that we have quite a lot of options [and are in a] strong position so choose what makes the most sense strategically,” he said. “We’ve been fortunate with investors. The prime thing is vision match: do they think about the long-term future in the same way we do? Do they have the same values and priorities? Generation nailed that on so many levels as a firm.”

Asana’s growth and mission both mirror trends in the wider world of enterprise IT and collaboration within it.

Slack, Microsoft Teams, Workplace from Facebook and other messaging and chat apps have transformed how coworkers communicate with each other, both within single offices and across wider geographies: they have replaced email, phone and other communication channels to some extent.

Meanwhile, the rise of cloud-based services like Dropbox, Box, Google Cloud, AWS and Microsoft’s Azure have transformed how people in organizations manage and ultimately collaborate on files: the rise of mobile and mobile working have increased the need for more flexible file management and access.

The third area that has been less covered is work management: as people continue to multitask on multiple projects – partly spurred by the rise in the other two collaboration categories – they need a platform that helps keep them organised and on top of all that work. This is where Asana sits.

“We think about collaboration as three markets,” Moskovitz said, “file collaboration, messaging, and work management. Each of these has a massive surface area and depth to them. We think it’s important that all companies have tools that they use from each of these big buckets.”

It is not the only one in that big bucket.

Asana alternatives include Airtable, Wrike, Trello and Basecamp. As we have pointed out before, that competitive pressure is another reason Asana is on the path to continue growing and making its service more sticky.

Indeed, just earlier this month Airtable raised $100 million at a $1.1 billion valuation. Airtable has a different approach – its platform can be used for more than project management – but it’s most definitely used to build templates precisely to track projects.

You might even argue that Airtable’s existing offering could present a type of product roadmap for what might be considered next for Asana.

For now, though, Asana is building up big customers for its existing services.

The product initially got its start when Moskovitz and Rosenstein – as respectively as co-founder and early employee of Facebook – built something to help their coworkers at the social network manage their workloads. Now, it has a range of users that include a number of other tech firms, but also others.

London’s National Gallery, for example, uses Asana to plan and launch exhibitions and business projects; the supermarket chain Tesco’s digital campaigns; Sony Music, which also uses it for marketing management but also to track a digitization project for its back music catalog; Uber, which has managed some 600 city expansions through Asana to date.

“At Generation Investment Management, we’re grounded in the philosophy that through strategic investments in leading, mission-driven companies we can move towards a more sustainable future,” said Colin le Duc, co-founder and partner, Generation Investment Management, in a statement.

“We see Collaborative Work Management as a distinct and rapidly expanding segment, and Asana has the right product and team to lead the market. Through Dustin and the team, Asana is changing how businesses around the world collaborate, epitomizing what it means to deliver results with a mission-driven ethos.”

Powered by WPeMatico

After eight years of bootstrapping, Deputy sought scale. So the workforce management platform turned to venture capital, quickly raising a $25 million Series A in early 2017. Today, Deputy is announcing a major accomplishment: the close of an $81 million round — the largest Series B in Australian history.

IVP led the investment for the Sydney and Atlanta-headquartered company, with support from OpenView Venture Partners, Square Peg Capital and Equity Venture Partners. Deputy plans to invest the funds in engineering and product, building out those teams in both HQs.

Co-founder and chief executive officer Ashik Ahmed declined to disclose the valuation.

Deputy’s employee management tool makes scheduling, time sheets, tasks and workplace communication easier for hourly and shift workers. Ahmed tells TechCrunch the 10-year-old company has 90,000 customers in 80 countries, including Amazon, Google, McDonald’s, Compass and Uber. It’s scheduled some 200 million shifts, or 1.2 billion hours of work, and facilitated more than $30 billion in payroll payments.

“Right now, the company grows every month as much as we did in [the first] six years,” Ahmed said. “Our growth … has really skyrocketed.”

Ahmed credits that growth to support from VCs.

“It’s not about the money but more about the expertise that we have been able to bring in,” he said. “OpenView, for example, has been really, really instrumental for the next stage of our journey.”

Deputy co-founder and CEO Ashik Ahmed

Around the globe, most workers earn money on an hourly basis. In the U.S., according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ data from 2015, roughly 80 million workers were hourly, or about 60 percent of all wage and salary workers in the country.

“The world of work is changing,” he said. “We are becoming more about instant gratification, we want what we want when we want it, and work is no different.”

“If businesses of today do not recognize the change that is happening, if they don’t adapt to it, they will become irrelevant tomorrow. Our goal is to help our customers adapt to this change by offering more flexibility in how they engage their workers. Our vision is to help these businesses thrive in the future world.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Second Home, the “creative workspace” company co-founded by Rohan Silva, a former tech and startup policy advisor for then British Prime Minister David Cameron, is closing in on a new funding round, TechCrunch has learned.

According to sources, the London startup, which is also co-founded by Sam Aldenton, has secured £20 million in investment from Boston-based investor Gerald Chan, who owns Hang Lung Group with his brother Ronnie Chan. Both were the first investors in Xiaomi, and Gerald Chan recently gave the biggest-ever philanthropic gift to Harvard University, totaling a hefty $350 million.

I understand that the injection of capital will be used to expand to L.A. in the U.S., and possibly another five locations, as Second Home continues to scale up its operations and the number of physical locations it has under management. The funding could be announced as soon as next week.

Second Home’s existing investors include: Yuri Milner, Index Ventures, Atomico, Talis Capital, Tencent founder Martin Lau and former Goldman Sachs chief economist Jim O’Neill.

The company’s original East London site opened in November 2014. It then opened Second Home Lisbon in 2016, and added another London space in Holland Park this year. A third London Second Home in Clerkenwell Green will open its doors next month.

I’m told that all three are fully occupied, and Silva has previously said that 97 percent of new customers come via referrals and other “organic channels.”

Meanwhile, the companies, charities and teams based at Second Home across various sites include energy upstart Bulb (which employs 280 people located at Spitalfields), Threads Styling, Help Refugees, Kickstarter, TaskRabbit, Vice Media, Spotify, Volkswagen, Taylor Wessing, Ermenegildo Zegna and others.

Silva couldn’t be reached for comment at the time of publication. I’ll update this article if and when I hear back.

Powered by WPeMatico

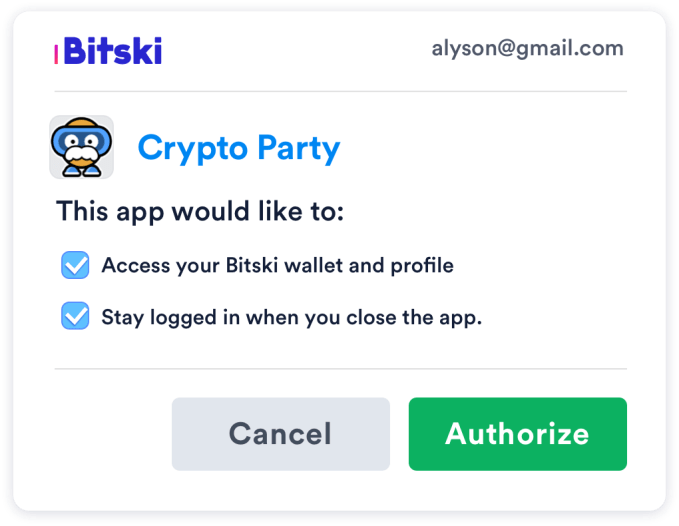

The mainstream will never adopt blockchain-powered decentralized apps (dApps) if it’s a struggle to log in. They’re either forced to manage complex security keys themselves, or rely on a clunky wallet-equipped browser like MetaMask. What users need is for signing in to blockchain apps to be as easy as Login with Facebook. So that’s what Bitski built. The startup emerges from stealth today with an exclusive on TechCrunch about the release of the developer beta of its single sign-on cryptocurrency wallet platform.

Ten projects, including 7 game developers, are lined up to pay a fee to integrate Bitski’s SDK. Then, whenever they need a user’s identity or to transact a payment, their app pops open a Bitski authorization screen, where users can grant permissions to access their ID, send money or receive items. Users sign up just once with Bitski, and then there’s no more punching in long private keys or other friction. Using blockchain apps becomes simple enough for novices. Given the recent price plunge, the mainstream has been spooked about speculating on cryptocurrencies. But Bitski could unlock the utility of dApps that blockchain developers have been promising but haven’t delivered.

“One of the great challenges for protocol teams and product companies in crypto today is the poor UX in dApps, specifically onboarding, transactions, and sign-in/password recovery,” says co-founder and CEO Donnie Dinch. “We interviewed a ton of dApp developers. The minute they used a wallet, there was a huge drop-off of folks. Bitski’s vision is to solve user onboarding and wallet usability for developers, so that they can in-turn focus on creating unique and useful dapps.”

The scrappy Bitski team raised $1.5 million in pre-seed capital from Steve Jang’s Kindred Ventures, Signia, Founders Fund, Village Global and Social Capital. They were betting on Dinch, a designer-as-CEO who’d built concert discovery app WillCall that he sold to Ticketfly, which was eventually bought by Pandora. After 18 months of rebranding Ticketfly and overhauling its consumer experience, Dinch left and eventually recruited engineer Julian Tescher to come with him to found Bitski.

Bitski co-founder and CEO Donnie Dinch

After Riff failed to hit scale, the team hung up its social ambitions in late 2017 and “started kicking around ideas for dApps. We mocked up a Venmo one, a remittance app…but found the hurdle to get someone to use one of these products is enormous,” Dinch recalls. “Onboarding was a dealbreaker for anyone building dApps. Even if we made the best crypto Venmo, to get normal people on it would be extremely difficult. It’s already hard enough to get people to install apps from the App Store.” They came up with Bitski to let any developer ski jump over that hurdle.

Looking across the crypto industry, the companies like Coinbase and Binance with their own hosted wallets that permitted smooth UX were the ones winning. Bitski would bring that same experience to any app. “Our hosted wallet SDK lets developers drop the Bitski wallet into their apps and onboard users with standards web 2.0 users have grown to know and love,” Dinch explains.

Imagine an iOS game wants to reward users with a digital sword or token. Users would have to set up a whole new wallet, struggle with their credentials or use another clumsy solution. They’d have to own Ethereum already to pay the Ethereum “gas” price to power the transaction, and the developer would have to manually approve sending the gift. With Bitski, users can approve receiving tokens from a developer from then on, and developers can pay the gas on users’ behalf while triggering transactions programmatically.

Magik is an AR content platform that’s one of Bitski’s first developers. Magik’s founders tell me, “We’re building towards reaching millions of mainstream consumers, and Bitski is the only wallet solution that understands what we need to reach users at that scale. They provide a dead-simple, secure and familiar interface that addresses every pain point along the user-onboarding journey.”

Bitski will offer a free tier, priced tiers based on transaction volume or a monthly fee and an enterprise version. In the future, the company is considering doubling-down on premium developer services to help them build more on top of the blockchain. “We will never, ever monetize user data. We’ve never had any intent at looking at it,” Dinch vows. The startup hopes developers will seize on the network effects of a cross-app wallet, as once someone sets up Bitski to use one product, all future sign-ins just require a few clicks.

In August, Coinbase acquired a startup called Distributed Systems that was building a similar crypto identity platform called the Clear Protocol. A “login with Coinbase” feature could be popular if launched, but the company’s focus is to spread a ton of blockchain projects. “If [login with Coinbase] launched tomorrow, they wouldn’t be able to support games or anything with a unique token. We’re a lockbox, they’re a bank,” Dinch claims.

The spectre of single sign-on’s biggest player, Facebook, looms, as well. In May it announced the formation of a blockchain team we suspect might be working on a crypto login platform or other ways to make the decentralized world more accessible for mom and pop. Dinch suspects that fears about how Facebook uses data would dissuade developers and users from adopting such a product. Still, Bitski’s haste in getting its developer platform into beta just a year after forming shows it’s eager to beat them to market.

Building a centralized wallet in a decentralized ecosystem comes with its own security risks. But Dinch assures me Bitski is using all its own hardware with air-gapped computers that have been stripped of their Wi-Fi cards, and it’s taking other secret precautions to prevent anyone from snatching its wallets. He believes cross-app wallets will also deliver a future where users actually own their virtual goods instead of just relying on the good will of developers not to pull them away or shut them down.” The idea of we’ve never been able to provably own unique digital assets is crazy to me,” Dinch notes. “Whether it’s a skin in Fortnite or a movie on iTunes that you purchase, you don’t have liquidity to resell those things. We think we’ll look back in 5 to 10 years and think it’s nuts that no one owned their digital items.”

While the crypto prices might be cratering and dApps like Cryptokitties have cooled off, Dinch is convinced the blockchain startups won’t fade away. “There is a thriving developer ecosystem hellbent on bringing the decentralized web to reality; regardless of token price. It’s a safe assumption that prices will dip a bit more, but will eventually rise whenever we see real use cases for a lot of these tokens. Most will die. The ones that succeed will be outcome-oriented, building useful products that people want.” Bitski’s a big step in that direction.

Powered by WPeMatico

PlayVS, the company bringing esports infrastructure to high schools across the country, has today announced the close of a $30.5 million Series B financing. The round was led by Elysian Park Ventures, the investment arm of the L.A. Dodgers, with participation from five existing investors, including New Enterprise Associates, Science Inc., Crosscut Ventures, Coatue Management and WndrCo.

New investors also joined in on the round, including Adidas (the company’s first esports investment), Samsung NEXT, Plexo Capital, as well as angel investors such as Sean “Diddy” Combs, David Drummond, DST Global partner Rahul Mehta, Michael Dubin and others.

It’s certainly worth noting that PlayVS raised a $15 million Series A just six short months ago. Founder and CEO Delane Parnell explained that this Series B was an opportunistic raise, as the company received a lot of inbound from investors to get a slice of the next round.

“This gives us much more stability and runway so that we can hire more senior employees and leadership,” said Parnell. “It also gives us a bit of a war chest to let the team go out and work their strategies.”

Alongside the raise, PlayVS also announced new game partnerships, bringing Rocket League and SMITE into the company’s portfolio. Rocket League and SMITE join League of Legends, which was added to the platform two months ago.

PlayVS launched early this year with a relatively novel approach to the esports world. Instead of focusing on the current esports space, PlayVS realized there was a huge opportunity to bring infrastructure to the esports landscape in high school. As more and more esports careers are created through investment by colleges (via scholarships) and esports orgs, PlayVS gives students a place to show off their skills and get in front of recruiters.

The first step in the process was establishing a partnership between PlayVS and the NHFS, which is essentially the NCAA of high school sports. Through that partnership, PlayVS handles team schedules, district league schedules, coaching clinics and referees, and sets up an in-person live spectator event for the State Championship at the end of the year.

Right now, the company is in the midst of its Season Zero, testing out the platform with a small number of states — Connecticut, Georgia, Kentucky, Massachusetts and Rhode Island — in preparation for the official Inaugural Season, which will begin in 2019. Today, PlayVS is adding Alabama (AHSAA), Mississippi (MISSHSAA) and parts of Texas (TCSAAL).

But the growth of the company is largely dependent on states and school districts, which is why PlayVS is announcing the launch of Club Leagues. Club Leagues is identical to the PlayVS sports league product, except there is no State Championship at the end. Still, students who do not yet have access to the official PlayVS sports league can create teams, join up and play matches.

Eventually, Parnell says, the company will phase out Club Leagues as soon as official sports leagues are available to those players.

Powered by WPeMatico

“I wasn’t asking to pay in Bitcoin!” Plastiq CEO and co-founder Eliot Buchanan recalls with a laugh. “I went to pay part of my tuition at Harvard and I was told that they didn’t (and never would) accept credit cards. It was inconvenient and seemed odd. Credit cards had been around for 50 years.” That set off the a light bulb in his head. “Why couldn’t I use a credit card to pay for this important bill? So, I set out to solve my own problem.”

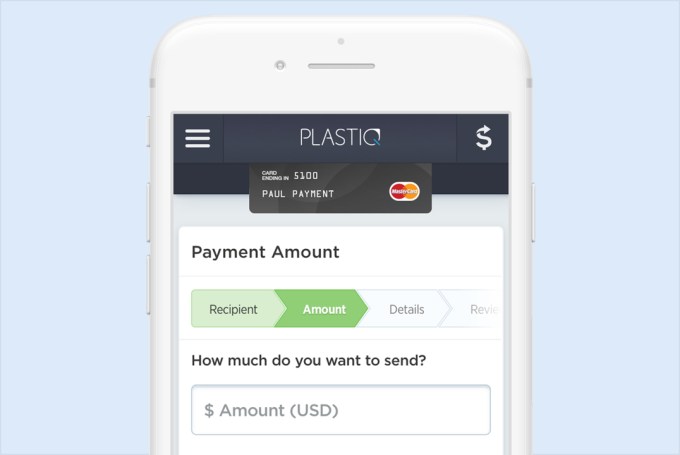

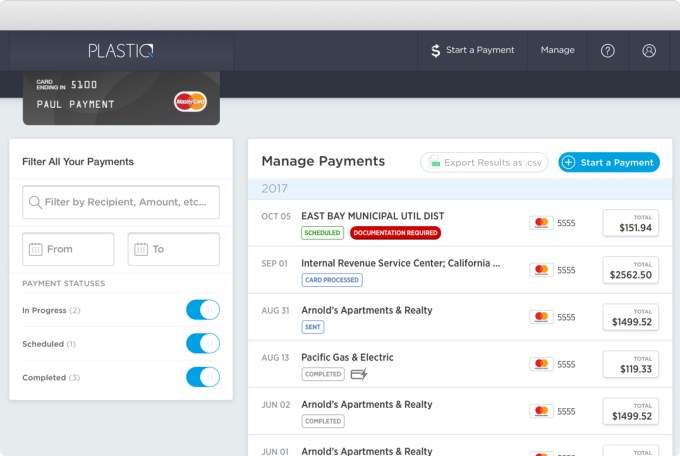

Whether you’re trying to pay your rent or tuition on credit, or you have a business and want to invest in a new opportunity or get a better rate by paying vendors up front, Plastiq can help. For a flat 2.5 percent fee, you pay Plastiq through your credit card, and it issues the proper wire transfer, check or deposit for up to $500,000, or even more, on your behalf to whomever you owe.

Now with more than 1 million clients, growth-stage VCs are taking notice. Kleiner Perkins has just led a $27 million Series C for Plastiq with partner Ilya Fushman joining the board. A source says the raise that also comes from DST Global between doubles and triples Plastiq’s valuation over its 2017 Series B-1 rounds of $11 million and $16 million. Now with $73 million in total funding, it plans to add 100 people to its current team of 60, while building out its small business product and bank partnerships.

“As tens of thousands of business owners started using Plastiq actively for billions of dollars in payments, we realized we had this incredible opportunity to serve as the hub/platform on which they (SMBs) could run all their payments. The very fabric of America’s economy — and certainly much of the world — is run by rising or aspiring small business owners,” Buchanan tells me. He says that’s “the main reason that seeded this Kleiner financing and our renewed vision to ‘accelerate how small businesses grow.’ [Helping people pay with credit cards] is merely the entry point to a much broader play where we are central to how a small business runs.”

For example, if a small business wants to ramp up production of something it’s selling, it’d typically have to pay up front for manufacturing, but wait months until the stuff is shipped and sold to recoup its investment. That can put a major squeeze on the company’s operating capital. With Plastiq, the business can pay with credit up front so they don’t have to worry about being in danger of running out of money in the meantime. Plastiq also lets businesses accept credit card payments, which can win them favor with partners.

Plastiq co-founders (from left): Eliot Buchanan and Dan Choi

Specialty medical clinic chain Metro Vein pays vendors who don’t take credit with Plastiq instead. “I was able to invest in a new line of business that has enabled me to more than double our revenues in the last 10 months,” said CEO Dmitri Ivanov. And thanks to tax write-offs, business users of Plastiq can push its realized fee down to 2 percent.

Buchanan claims Plastiq doesn’t have any direct competitors that allow SMBs to pay for all their bills via credit. It does carry platform risk, though. “Like any payments business, we rely heavily on Visa, MasterCard and American Express. A challenge or risk factor is that you’re relying on very large companies that are very successful. You have to learn to work hand in hand with those partners instead of ‘disrupt them.’” He says Plastiq’s relationships with them are positive right now since it’s driving new revenue for them and helping their customers spend in new areas.

There’s also the risk that people misuse Plastiq to procrastinate on actually paying their personal bills or get in over their head investing in their business. But Plastiq’s new board member Fushman calls the service “this elegant way for businesses to tap into credit they’ve been issued but they haven’t been able to utilize before.” For many who are happy to pay though just need some time and flexibility, Plastiq can pitch in.

Powered by WPeMatico