funding

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

In developing VC markets such as the Midwest, some may think that funding from the government or economic development organizations are a godsend for local entrepreneurs. Startups are often looking for all the help they can get, and a boost in funds or an attractive set of economic incentives can be perceived as the fuel they need to take the next step in their growth journey.

While this type of funding can be helpful, a startup should ensure that funding from these sources is not a double-edged sword. The biggest positive, of course, is the money, which can help startups with product development, hiring, marketing, sales and more. But there can also be certain restrictions or limitations that are not fully understood initially—these restrictions could hinder growth at an inopportune time later on.

The inevitable question, then, is should startups consider partnering with the government or various economic development groups as they look to get off the ground? Let’s take a closer look.

Today, particularly in the Midwest, it’s common for state and local governments to offer startups incentives such as tax exemptions or grants in an effort to keep local businesses around and also attract companies from other regions.

So how do these incentives work? When it comes to tax credits or exemptions, local governments are sometimes willing to provide these incentives if a startup can demonstrate how paying lower taxes will benefit the wider community.

Powered by WPeMatico

Exercise tech company Peloton filed confidentially for IPO this week, and already the big question is whether their last private valuation at $4 billion might be too rich for the appetites of public market investors. Here’s a breakdown of the pros and cons leading up to the as-yet revealed market debut date.

The biggest thing to pay attention to when it comes time for Peloton to actually pull back the curtains and provide some more detailed info about its customers in its S-1. To date, all we really know is that Peloton has “more than 1 million users,” and that’s including both users of its hardware and subscribers to its software.

The mix is important – how many of these are actually generating recurring revenue (vs. one-time hardware sales) will be a key gauge. MRR is probably going to be more important to prospective investors when compared with single-purchases of Peloton’s hardware, even with its premium pricing of around $2,000 for the bike and about $4,000 for the treadmill. Peloton CEO John Foley even said last year that bike sales went up when the startup increased prices.

Hardware numbers are not entirely distinct from subscriber revenue, however: Per month pricing is actually higher with Peloton’s hardware than without, at $39 per month with either the treadmill or the bike, and $19.49 per month for just the digital subscription for iOS, Android and web on its own.

That makes sense when you consider that its classes are mostly tailored to this, and that it can create new content from its live classes which occur in person in New York, and then are recast on-demand to its users (which is a low-cost production and distribution model for content that always feels fresh to users).

Powered by WPeMatico

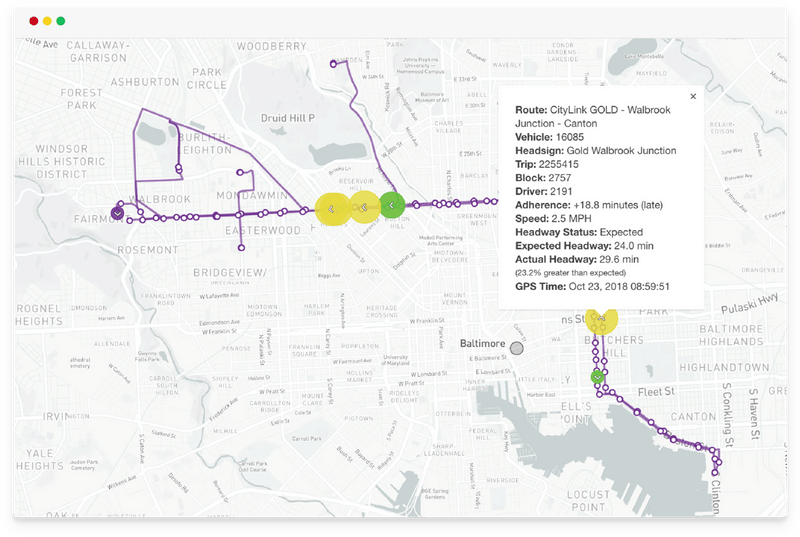

Swiftly just raised a $10 million Series A round led by VIA ID, Aster Capital, Renewal Funds and Wind Capital to grow its software-as-a-service business for cities’ transportation agencies. lt works by helping cities manage their transit systems and identify points in the schedule or route that negatively impact service efficiency and reliability.

Swiftly also offers real-time passenger info that will “predict when the bus will arrive in a way that is much more accurate than the current system,” Swiftly co-founder and CEO Jonny Simkin told TechCrunch. In fact, Simkin says Swiftly is up to 30% more accurate than current systems.

“It’s one thing to tell someone their bus is 10 minutes delayed, but if we can get to the root of the problem, it’s better for the city and stimulates the economy,” he said.

That’s where Swifty’s data platform comes in to gather insights and analyze historical data to rethink route planning and where to place stops. In one city, these insights led the customer to implement processes to change lights to green when a bus is running behind schedule.

Swiftly currently works with more than 50 cities and 2,500 transit professionals throughout the country. That comes out to powering more than 1.2 billion passenger trips per year. If you’ve never heard of Swiftly, you’re not alone. And that’s by design.

Swiftly is meant to be behind-the-scenes software that enables local transportation agencies to better manage their fleets and offerings to their respective riders. Swiftly’s customer is generally either a transit agency, a city or department of transportation.

“They buy our platform because they want to improve the passenger experience, and improve service reliability and efficiency,” Simkin said.

For the passenger, they experience Swiftly when they open Google Maps and look for transit routes or when they open a city’s specific transit service. One of Swiftly’s customers is the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority in San Jose, Calif. Its CIO, Gary Miskell, says Swiftly is one of the authority’s early innovation partners.

“With Swiftly’s innovative product development, VTA has been able to improve our real time information accuracy and provide cutting edge data to our planning and operations staff thus improving our transit system performance,” Miskell said in a statement.

With the funding, the plan is to expand to several hundred cities in the U.S. and worldwide.

“Public transit is very important to our communities and cities and it’s something that needs to be more efficient,” Simkin said. “Public transit is this extensive piece of the community and there to serve everyone, but often times those tools fall short.”

Powered by WPeMatico

The rising popularity of omni-channel commerce — selling to customers wherever they happen to be spending time online — has spawned an army of shopping tools and platforms that are giving legacy retail websites and marketplaces a run for their money. Now, one of the faster growing of these is announcing an impressive round of funding to stay on trend and continue building its business.

Depop, a London startup that has built an app for individuals to post and sell (and mainly resell) items to groups of followers by way of its own and third-party social feeds, has closed a Series C round of $62 million led by General Atlantic. Previous investors HV Holtzbrinck Ventures, Balderton Capital, Creandum, Octopus Ventures, TempoCap and Sebastian Siemiatkowski, founder and CEO of Swedish payments company Klarna, all also participated.

The funding will be used in a couple of areas. First, to continue building out the startup’s technology — building in more recommendation and image detection algorithms is one focus.

And second, to expand in the U.S., which CEO Maria Raga said is on its way to being Depop’s biggest market, with 5 million users currently and projections of that going to 15 million in the next three years.

That’s despite strong competition from other peer-to-peer selling platforms like Vinted and Poshmark, and social platforms that have been doubling down on commerce, like Instagram and Pinterest. On the other hand, the opportunity is big: A recent report from ThredUp, another second-hand clothes sales platform, estimated that the total resale market is expected to more than double in value to $51 billion from $24 billion in the next five years, accounting for 10% of the retail market.

Prior to this, Depop had raised just under $40 million. It’s not disclosing its valuation except to say it’s a definite up round. “I’m extremely happy,” Raga said when I asked her about it this week.

The funding comes on the heels of strong growth and strong focus for the startup.

If “social shopping,” “selling to groups of followers,” and the “use of social feeds” (or my headline…) didn’t already give it away, Depop is primarily aimed at millennial and Gen Z consumers. The company said that about 90% of its active users are under the age of 26, and in its home market of the U.K. it’s seen huge traction, with one-third of all 16 to 24-year-olds registered on Depop.

Its rise has dovetailed with some big changes that the fashion industry has undergone, said Raga. “Our mission is to redefine the fashion industry in the same way that Spotify did with music, or Airbnb did with travel accommodation,” she said.

“The fashion world hasn’t really taken notice” of how things have evolved at the consumer end, she continued, citing concerns with sustainability (and specifically the waste in the fashion industry), how trends are set today (no longer dictated by brands but by individuals) and how anything can be sold by anyone, from anywhere, not just from a store in the mall, or by way of a well-known brand name website. “You can now start a fashion business from your bedroom,” she added.

For this generation of bedroom entrepreneurs, social apps are not a choice, but simply the basis and source of all their online engagement. Depop notes that the average daily user opens the app “several times per day” both to browse things, check up on those that they follow, to message contacts and comment on items and, of course, to buy and sell. On average, Depop users collectively follow and message each other 85 million times each month.

This rapid uptake and strong usage of the service has driven it to 13 million users, revenue growth of 100% year-on-year for the past few years and gross merchandise value of more than $500 million since launch. (Depop takes a 10% cut, which would work out to total revenues of about $50 million for the period.)

When we first wrote about Depop back in 2015 (and even prior to that), the startup and app were primarily aiming to provide a way for users to quickly snap pictures of their own clothes and other used items to post them for sale, one of a wave of flea-market-inspired apps that were emerging at that time. (It also had an older age group of users, extending into the mid-thirties.)

Fast-forward a few years and Depop’s growth has been boosted by an altogether different trend: the emergence of people who go to great efforts to buy limited editions of collectable, or just currently very hot, items, and then resell them to other enthusiasts. The products might be lightly used, but more commonly never used, and might include limited-edition sneakers, expensive t-shirts released in “drops” by brands themselves or items from one-off capsule collections.

It may have started as a way of decluttering by shifting unused items of your own, but it’s become a more serious endeavor for some. Raga notes that Depop’s top sellers are known to clear $100,000 annually. “It’s a real business for them,” she said.

And Depop still sells other kinds of goods, too. These pressed-flower phone cases, for example, have seen a huge amount of traction on Twitter, as well as in the app itself in the last week:

Ordered a new phone case off this woman from depop who makes them with pressed flowers n she sent me this :’) pic.twitter.com/oBtRtQ1MJc

— megan (@__meganbenson) June 1, 2019

Alongside its own app and content shared from there to other social platforms, Depop extends the omnichannel approach with a selection of physical stores, too, to showcase selected items.

The startup has up to now taken a very light-touch approach to the many complexities that can come with running an e-commerce business — a luxury that’s come to it partly because its sellers and buyers are all individuals, mostly younger individuals and, leaning on the social aspect, the expectation that people will generally self-police and do right by each other, or risk getting publicly called out and lose business as a result.

I think that as it continues to grow, some of that informality might need to shift, or at least be complemented with more structure.

In the area of shipping, buyers generally do not seem to expect the same kind of shipping tracking or delivery professionals appearing at their doors. Sellers handle all the shipping themselves, which sometimes means that if the buyer and seller are in the same city, an in-person delivery of an item is not completely unheard of. Raga notes that in the U.S. the company has now at least introduced pre-paid envelopes to help with returns (not so in the U.K.).

Payments come by way of PayPal, with no other alternatives at the moment. Depop’s 10% cut on transactions is in addition to PayPal’s fees. But having the Klarna founder as a backer could pave the way for other payment methods coming soon.

One area where Depop is trying to get more focused is in how its activities line up with state laws and regulations.

For example, it currently already proactively looks for and takes down posts offering counterfeit or other illicit goods on the platform, but also relies on people or brands reporting these. (Part of the tech investment into image detection will be to help improve the more automated algorithms, to speed up the rate at which illicit items are removed.)

Then there is the issue of tax. If top sellers are clearing $100,000 annually, there are taxes that will need to be paid. Raga said that right now this is handed off to sellers to manage themselves. Depop does send alerts to sellers, but it’s still up to the sellers themselves to organise sales tax and other fees of that kind.

“We are very close to our top sellers,” Raga said. “We’re in contact on a daily basis and we inform of what they have to do. But if they don’t, it’s their responsibility.”

While there is a lot more development to come, the core of the product, the approach Depop is taking and its success so far have been the winning combination to bring on this investment.

“Technology continues to transform the retail landscape around the world and we are incredibly excited to be investing in Depop as it looks to capture the huge opportunity ahead of it,” said Melis Kahya, General Atlantic head of Consumer for EMEA, in a statement. “In a short space of time the team has developed a truly differentiated platform and globally relevant offering for the next generation of fashion entrepreneurs and consumers. The organic growth generated in recent years is a testament to the impact they are having and we look forward to working with the team to further accelerate the business.”

Powered by WPeMatico

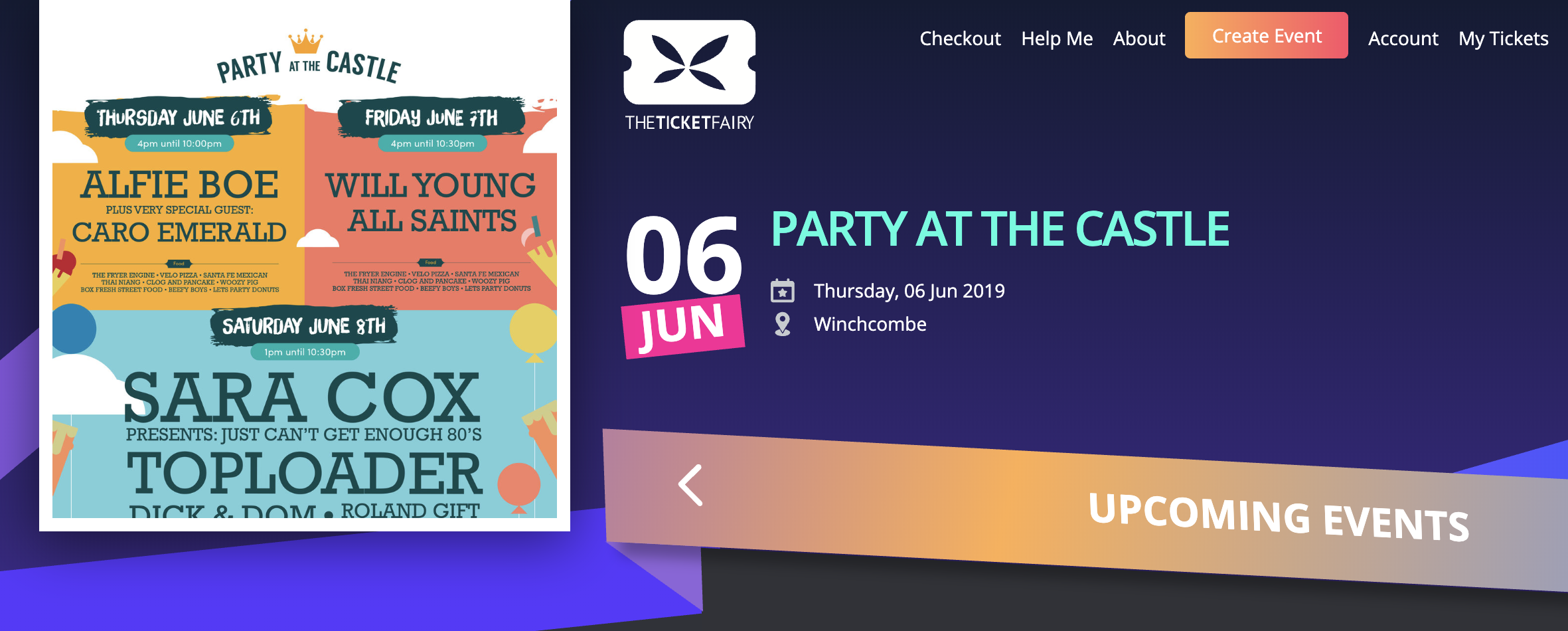

Ticketmaster’s dominance has led to ridiculous service fees, scalpers galore and exclusive contracts that exploit venues and artists. The moronic approval of venue operator and artist management giant Live Nation’s merger with Ticketmaster in 2010 produced an anti-competitive juggernaut. It pressures venues to sign ticketing contracts under veiled threat that artists would otherwise be routed to different concert halls. Now it’s become difficult for venues, artists and fans to avoid Ticketmaster, which charges fees as high as 50% that many see as a ripoff.

The Ticket Fairy wants to wrestle away from Ticketmaster control of venues while giving fans ways to earn tickets for referring their friends. The startup is doing that by offering the most technologically advanced ticketing platform that not only handles sales and check-ins, but acts as a full-stack Salesforce for concerts that can analyze buyers and run ad campaigns while thwarting scalpers. Co-founder Ritesh Patel says The Ticket Fairy has increased revenue for event organizers by 15% to 25% during its private beta focused on dance music festivals.

Now after 850,000 tickets sold, it’s officially launching its ticketing suite and actively poaching venues from Eventbrite as it moves deeper into esports and conventions. With a little more scale, it will be ready to challenge Ticketmaster for lucrative clients.

Ritesh’s combination of product and engineering skills, rapid progress and charismatic passion for live events after throwing 400 of his own has attracted an impressive cadre of angel investors. They’ve delivered a $2.5 million seed round for Ticket Fairy, adding to its $485,000 pre-seed from angels like Twitch/Atrium founder Justin Kan, Twitch COO Kevin Lin and Reddit CEO Steve Huffman.

The new round includes YouTube founder Steve Chen, former Kleiner Perkins partner (and Mark’s sister) Arielle Zuckerberg and funds like 500 Startups, ex-Uber angels Fantastic Ventures, G2 Ventures, Tempo Ventures and WeFunder. It’s also scored music industry angels like Serato DJ hardware CEO AJ Bertenshaw, Spotify’s head of label licensing Niklas Lundberg, and celebrity lawyer Ken Hertz, who reps Will Smith and Gwen Stefani.

“The purpose of starting The Ticket Fairy was not to be another Eventbrite, but to reduce the risk of the person running the event so they can be profitable. We’re not just another shopping cart,” Patel says. The Ticket Fairy charges a comparable rate to Eventbrite’s $1.59 + 3.5% per ticket plus payment processing that brings it closer to 6%, but Patel insists it offers far stronger functionality.

Constantly clad in his golden disco hoodie over a Ticket Fairy t-shirt, Patel lives his product, spending late nights dancing and taking feedback at the events his clients host. He’s been a savior of SXSW the past two years, injecting the aging festival that shuts down at 2am with multi-night after-hours raves. Featuring top DJs like Pretty Lights in creative locations cab drivers don’t believe are real, The Ticket Fairy’s parties have won the hearts of music industry folks.

The Ticket Fairy co-founders. Center and inset left: Ritesh Patel. Inset right: Jigar Patel

Now the Y Combinator startup hopes its ticketing platform will do the same thanks to a slew of savvy features:

Still, the biggest barrier to adoption remains the long exclusive contracts Ticketmaster and other giants like AEG coerce venues into in the U.S. Abroad, venues typically work with multiple ticket promoters who sell from the same pool, which is why 80% of The Ticket Fairy’s business is international right now. In the U.S., ticketing is often handled by a single company, except for the 8% of tickets artists can sell however they want. That’s why The Ticket Fairy has focused on signing up non-traditional venues for festivals, trade convention halls, newly built esports arenas, as well as concert halls.

“Coming from the event promotion background, we understand the risk event organizers take in creating these experiences,” The Ticket Fairy’s co-founder and Ritesh’s brother Jigar Patel explains. “The odds of breaking even are poor and many are unable to overcome those challenges, but it is sheer passion that keeps them going in the face of financial uncertainty and multi-year losses.” As competitors’ contracts expire, The Ticket Fairy hopes to swoop in by dangling its sales-boosting tech. “We get locked out of certain things because people are locked in a contract, not because they don’t want to use our system.”

The live music industry can be brutal, though. Events can have slim margins, organizers are loathe to change their process and it’s a sales-heavy process convincing them to try new software. But while the record business has been redefined by streaming, ticketing looks a lot like it did a decade ago. That makes it ripe for disruption.

“The events industry is more important than ever, with artists making the bulk of their income from touring instead of record sales, and demand from fans for live experiences is increasing at a global level,” Jigar concludes. “When events go out of business, everybody loses, including artists and fans. Everything we do at The Ticket Fairy has that firmly in mind – we are here to keep the ecosystem alive.”

Powered by WPeMatico

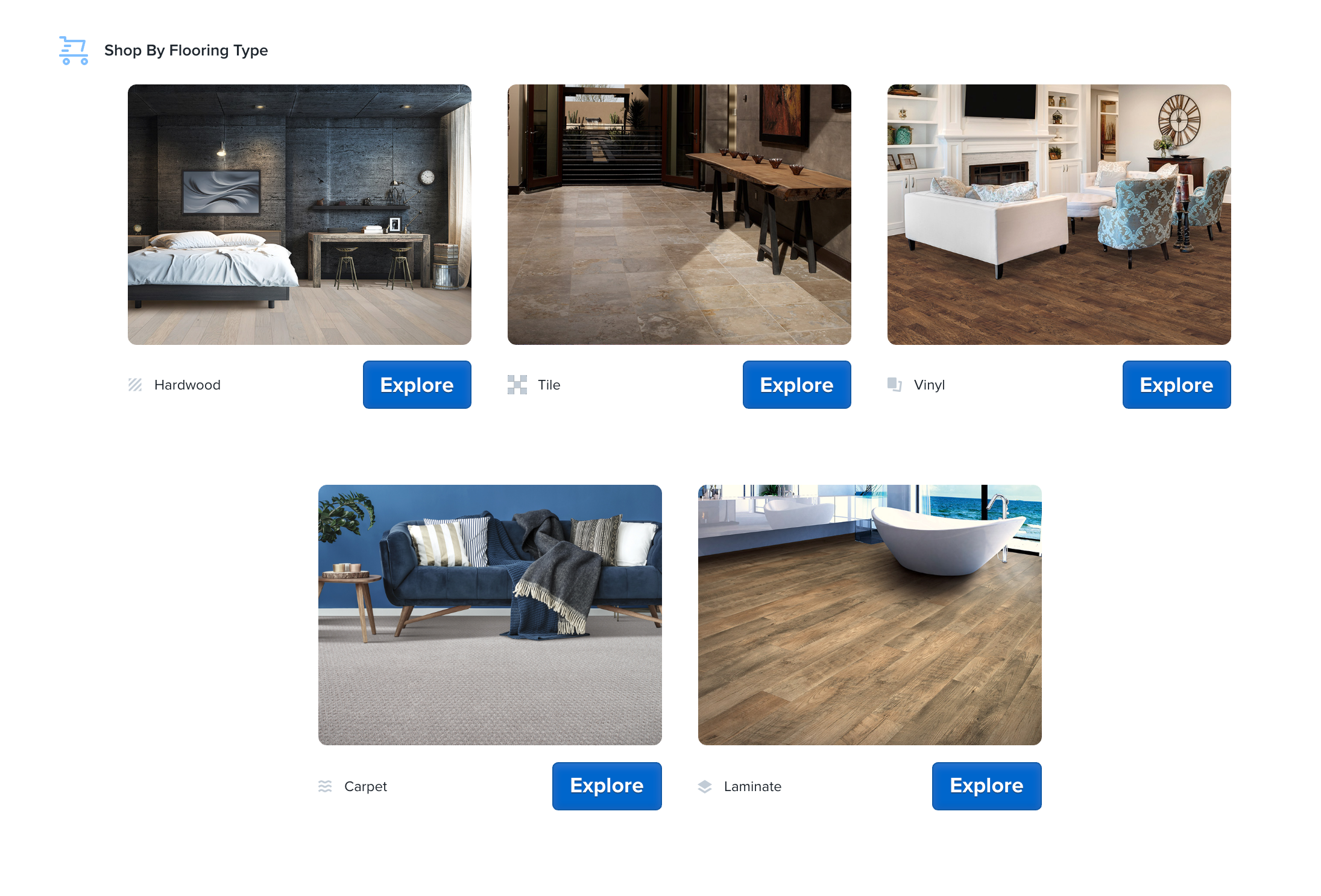

Why is an adtech startup going after the flooring industry?

That was my big question when I got on the phone with AdHawk CEO Todd Saunders and COO Dan Pratt. The company announced earlier this week that it’s raised a $13 million Series B round of funding in conjunction with the launch of a new website, FlooringStores.

“We look at AdHawk as the umbrella company,” Saunders explained. “Our core is a digital marketing company that’s built very strong machine learning. Now FloorForce is the brand we’re using to go after with the flooring vertical.”

FloorForce is actually a recent AdHawk acquisition, offering a variety of digital services for flooring companies — not just AdHawk’s specialty of Facebook and Google advertising, but also website building, reputation management and chatbots. FlooringStores, meanwhile, is the consumer-facing side of the business, a website where homeowners looking for flooring services can browse different providers

Saunders said FloorForce’s potential customer base includes the 20,000 independent flooring companies in the United states, all in an industry that, in his words, “hasn’t been touched by technology.”

Pratt added, “The vast majority of these retailers need to be convinced why … websites are important — or if they have one, it was built in 1997, which is obviously a really bad experience for consumers. In the same conversation where we’re pitching these websites for our retailers, we’re talking to them about other opportunities, like chatbots, and the universe of what is possible for these folks is magnified by 10x.”

Ultimately, Saunders and Pratt said they’re hoping to take a similar approach and expand into other home service verticals, all while taking advantage of the consumer data gathered through AdHawk and FloorForce.

AdHawk’s Series B was led by Entrée Capital, with participation from Table Management, Accomplice and others. The startup has now raised a total of $17.7 million, and Pratt said it’s been growing quickly — going from 30 employees a year ago to more than 100 currently, with the aim of approaching a headcount of 200 by the end of the year.

Powered by WPeMatico

When starting a tech company, there seems to be a playbook that most entrepreneurs follow. While some may start with a bit of bootstrapping, most will dive straight into raising seed money through investors. In many cases, this is a great path. It’s a path I’ve taken twice myself, first with GroupMe, and then again with Fundera.

Ironically, though, my second venture-backed company is a business focused on helping entrepreneurs find debt financing—a process I’ve gone through only once myself. But after five years of building and scaling this business, it’s made me take a step back and consider the question of when and where debt financing might be a better option for a business than equity financing, and vice versa.

I view these financing vehicles differently now than I did half a decade ago, and think it’s time we start to think a bit wider and diversely about how we finance our growing endeavors.

After all, when entrepreneurs take venture capital, they usually sign up to provide a 10x return on an investor’s capital. This expectation ultimately influences how they operate their business in the short-term. Maybe they’re not always ready for that expectation.

Or maybe they know they need to focus on building a good business before a great one. In this case, debt may be the better vehicle, where the only expectation is to pay it back.

Whether it’s money to get your business off the ground, capital to fuel additional growth, or cash to cover a gap, and whether you’re guiding the growth of a burgeoning startup, a smaller business, or even consulting firm helping other entrepreneurs, you should think critically about how you finance your business.

Here’s what to consider.

Powered by WPeMatico

There’s lots of data in the world these days, and there are a number of companies vying to store that data in data warehouses or lakes or whatever they choose to call it. Old-school companies have tended to be on prem, while new ones like Snowflake are strictly in the cloud. Yellowbrick Data wants to play the hybrid angle, and today it got a healthy $81 million Series C to continue its efforts.

The round was led by DFJ Growth with help from Next47, Third Point Ventures, Menlo Ventures, GV (formerly Google Ventures), Threshold Ventures and Samsung. New investors joining the round included IVP and BMW i Ventures. Today’s investment brings the total raised to a brisk $173 million.

Yellowbrick sees a world that many of the public cloud vendors like Microsoft and Google see, one where enterprise companies will be living in a hybrid world where some data and applications will stay on prem and some in the cloud. They believe this situation will be in place for the foreseeable future, so its product plays to that hybrid angle, where your data can be on prem or in the cloud.

The company did not want to discuss valuation in spite of the high amount of raised dollars. Neither did it want to discuss revenue growth rates, other than to say that it was growing at a healthy rate.

Randy Glein, partner at DFJ Growth, did say one of the things that attracted his company to invest in Yellowbrick was its momentum along with the technology, which in his view provides a more modern way to build data warehouses. “Yellowbrick is quickly providing a new generation of ultra-high performance data warehouse capabilities for large enterprises. The technology is a step function improvement on every dimension compared to legacy solutions, helping modern enterprises digest and interpret massive data workloads in a fraction of the time at a fraction of the cost,” he said in a statement.

It’s interesting that a company with just 100 employees would require this kind of money, but as company COO Jason Snodgress told TechCrunch, it costs a lot of money to build out a data warehouse. He’s not wrong. Snowflake, a company that’s building a cloud data warehouse, has raised almost a billion dollars.

Powered by WPeMatico

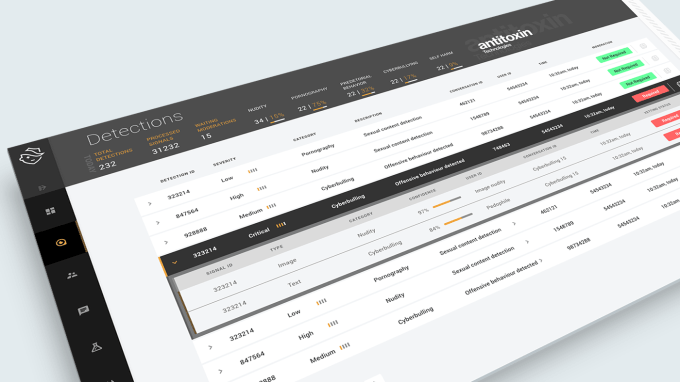

The big social networks and video games have failed to prioritize user well-being over their own growth. As a result, society is losing the battle against bullying, predators, hate speech, misinformation and scammers. Typically when a whole class of tech companies have a dire problem they can’t cost-effectively solve themselves, a software-as-a-service emerges to fill the gap in web hosting, payment processing, etc. So along comes AntiToxin Technologies, a new startup that wants to help web giants fix their abuse troubles with its safety-as-a-service.

It all started on Minecraft. AntiToxin co-founder Ron Porat is cybersecurity expert who’d started ad blocker Shine. Yet right under his nose, one of his kids was being mercilessly bullied on the hit children’s game. If even those most internet-savvy parents were being surprised by online abuse, Porat realized the issue was bigger than could be addressed by victims trying to protect themselves. The platforms had to do more, research confirmed.

A recent Ofcom study found almost 80% of children had a potentially harmful online experience in the past year. Indeed, 23% said they’d been cyberbullied, and 28% of 12 to 15-year-olds said they’d received unwelcome friend or follow requests from strangers. A Ditch The Label study found of 12 to 20-year-olds who’d been bullied online, 42% were bullied on Instagram.

Unfortunately, the massive scale of the threat combined with a late start on policing by top apps makes progress tough without tremendous spending. Facebook tripled the headcount of its content moderation and security team, taking a noticeable hit to its profits, yet toxicity persists. Other mainstays like YouTube and Twitter have yet to make concrete commitments to safety spending or staffing, and the result is non-stop scandals of child exploitation and targeted harassment. Smaller companies like Snap or Fortnite-maker Epic Games may not have the money to develop sufficient safeguards in-house.

“The tech giants have proven time and time again we can’t rely on them. They’ve abdicated their responsibility. Parents need to realize this problem won’t be solved by these companies” says AntiToxin co-founder and CEO Zohar Levkovitz, who previously sold his mobile ad company Amobee to Singtel for $321 million. “You need new players, new thinking, new technology. A company where ‘Safety’ is the product, not an after-thought. And that’s where we come-in.” The startup recently raised a multimillion-dollar seed round from Mangrove Capital Partners and is allegedly prepping for a double-digit millions Series A.

AntiToxin’s technology plugs into the backends of apps with social communities that either broadcast or message with each other and are thereby exposed to abuse. AntiToxin’s systems privately and securely crunch all the available signals regarding user behavior and policy violation reports, from text to videos to blocking. It then can flag a wide range of toxic actions and let the client decide whether to delete the activity, suspend the user responsible or how else to proceed based on their terms and local laws.

Through the use of artificial intelligence, including natural language processing, machine learning and computer vision, AntiToxin can identify the intent of behavior to determine if it’s malicious. For example, the company tells me it can distinguish between a married couple consensually exchanging nude photos on a messaging app versus an adult sending inappropriate imagery to a child. It also can determine if two teens are swearing at each other playfully as they compete in a video game or if one is verbally harassing the other. The company says that beats using static dictionary blacklists of forbidden words.

AntiToxin is under NDA, so it can’t reveal its client list, but claims recent media attention and looming regulation regarding online abuse has ramped up inbound interest. Eventually the company hopes to build better predictive software to identify users who’ve shown signs of increasingly worrisome behavior so their activity can be more closely moderated before they lash out. And it’s trying to build a “safety graph” that will help it identify bad actors across services so they can be broadly deplatformed similar to the way Facebook uses data on Instagram abuse to police connected WhatsApp accounts.

“We’re approaching this very human problem like a cybersecurity company, that is, everything is a Zero-Day for us” says Levkowitz, discussing how AntiToxin indexes new patterns of abuse it can then search for across its clients. “We’ve got intelligence unit alums, PhDs and data scientists creating anti-toxicity detection algorithms that the world is yearning for.” AntiToxin is already having an impact. TechCrunch commissioned it to investigate a tip about child sexual imagery on Microsoft’s Bing search engine. We discovered Bing was actually recommending child abuse image results to people who’d conducted innocent searches, leading Bing to make changes to clean up its act.

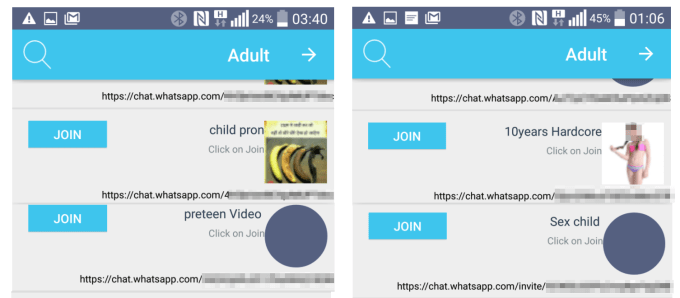

AntiToxin identified publicly listed WhatsApp Groups where child sexual abuse imagery was exchanged

One major threat to AntiToxin’s business is what’s often seen as boosting online safety: end-to-end encryption. AntiToxin claims that when companies like Facebook expand encryption, they’re purposefully hiding problematic content from themselves so they don’t have to police it.

Facebook claims it still can use metadata about connections on its already encrypted WhatApp network to suspend those who violate its policy. But AntiToxin provided research to TechCrunch for an investigation that found child sexual abuse imagery sharing groups were openly accessible and discoverable on WhatsApp — in part because encryption made them hard to hunt down for WhatsApp’s automated systems.

AntiToxin believes abuse would proliferate if encryption becomes a wider trend, and it claims the harm that it causes outweighs fears about companies or governments surveiling unencrypted transmissions. It’s a tough call. Political dissidents, whistleblowers and perhaps the whole concept of civil liberty rely on encryption. But parents may see sex offenders and bullies as a more dire concern that’s reinforced by platforms having no idea what people are saying inside chat threads.

What seems clear is that the status quo has got to go. Shaming, exclusion, sexism, grooming, impersonation and threats of violence have started to feel commonplace. A culture of cruelty breeds more cruelty. Tech’s success stories are being marred by horror stories from their users. Paying to pick up new weapons in the fight against toxicity seems like a reasonable investment to demand.

Powered by WPeMatico

Today, Peloton is a bonafide success. The company, which sells $2,245 internet-connected exercise bikes, boasts a $4 billion valuation and a cult following.

That hasn’t always been the case. For years, Peloton battled for venture capital investment and struggled to attract buyers. Now that it’s proven the market for tech-enabled home exercise equipment and affiliated subscription products, a whole bunch of startups are chasing down the same customer segment.

Mirror, a New York-based company that sells $1,495 full-length mirrors that double as interactive home gyms, is closing in a round of funding expected to reach $36 million, sources and Delaware stock filings confirm, at a valuation just under $300 million. It’s unclear who has signed on to lead the round; we’ve heard a number of high-profile firms looked at Mirror’s books and passed. The company has previously raised a total of $38 million from Spark Capital, First Round Capital, Lerer Hippeau, BoxGroup and more.

Mirror declined to comment for this story.

Like Peloton, Mirror is sold for a hefty fee with a subscription to the service’s unlimited live and on-demand workouts that comes at an additional cost. The company hasn’t disclosed subscriber numbers, though The New York Times reported in February the business was selling $1 million worth of Mirrors — or some 650 units — per month.

The company has not only benefited from the Peloton effect, but also from a near-immediate interest from celebrities and influencers in its product. Kate Hudson, Alicia Keys, Reese Witherspoon, Jennifer Aniston and Gwyneth Paltrow are among the many celebrities to have publicly boasted about Mirror, undoubtedly boosting sales for the up-and-coming startup.

Venture capitalists were quick to show support for Mirror, too; in fact, the business attracted money at a $200 million valuation prior to launching its first product. Mirror began selling its sleek equipment, dubbed by The New York Times as “The Most Narcissistic Exercise Equipment Ever,” in September.

SAN FRANCISCO, CA – SEPTEMBER 06: Mirror Founder and CEO Brynn Putnam (L) and moderator Lucas Matney speak onstage during Day 2 of TechCrunch Disrupt SF 2018 at Moscone Center on September 6, 2018, in San Francisco, California. (Photo by Steve Jennings/Getty Images for TechCrunch)

The round comes amid a distinct boom in funding for fitness-related startups evidenced not only by Peloton’s mammoth valuation and hyped-over initial public offering expected soon but by the rapid uptick in small upstarts looking to capitalize on rising interest in fitness apps and equipment. In total, VCs bet some $2 billion on U.S. fitness startups in 2018, a record amount of funding for the space. So far this year, nearly $500 million has been allocated to the growing sector, per PitchBook, as entrepreneurs strive to bring the gym into the home.

Tonal, which sells personal exercise equipment that combines on-demand training with smart features, is among a small class of venture-backed fitness companies to have accumulated a large following. The company has raised $91.7 million in equity funding at a valuation of $185 million, according to PitchBook, from investors including L Catterton, Shasta Ventures, Mayfield and Sapphire Sport.

When it comes to early-stage efforts, there’s no shortage of recent fundraises. Last week, Livekick, which gives customers access to one-on-one personal training and yoga from their home, closed a $3 million seed round led by Firstime VC. Two weeks ago, fitness startup Future secured an $8.5 million round led by Kleiner Perkins’ Mamoon Hamid. For a $150 monthly fee, Future assigns personalized workout plans and a coach who tracks customers’ fitness activity through an Apple Watch. To keep users committed to their workout regimens, Future sends daily text messages with motivational feedback.

The AI-based personal training company Aaptiv, Plankk, which sells live fitness lessons led by Instagram stars, and audio coaching app Eastnine, have also recently launched.

Mirror was founded in late 2016 by Brynn Putnam, an entrepreneur behind Refine Method, a chain of boutique fitness studios located in New York. The former professional dancer spoke to TechCrunch’s Lucas Matney at Disrupt San Francisco in September about the future of the business.

“[We want] to enhance the human touch rather than to replace it,” Putnam said. “Our goal is not to be the next treadmill in your life, our goal is to be the next screen in your home,” Putnam said.

Ultimately, Putnam added, Mirror plans to scale beyond fitness content with potential extensions including physical therapy, fashion, beauty and education.

“We have the ability to create personalized premium content across a wide range of verticals, with fitness being our first vertical,” Putnam said.

Powered by WPeMatico