Apps

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Auto Added by WPeMatico

Even in a non-hell year, running a successful startup is a tremendous lift. After the events of 2020, however, no doubt many already lean businesses are hanging on by the skin of their teeth. For every company that saw increased interest in their offerings during the pandemic, there were several that simply couldn’t make it through the finish line.

We’ve put this list together for several years now. It’s not a fun task, but it seems worthwhile to commemorate the startups that have closed up shop over the past 12 months. (Some of them were acquired by larger companies before shutting down, but all of them began their life as startups, and it still felt worthwhile to mark the end of their stories.) It also offers an opportunity to examine those issues from a bit of distance to see if there are any broader takeaways for the community at large.

This year’s list is among the most diverse we’ve done, ranging from standard smaller-name closures to big blockbuster crashes like Quibi and Essential . For some, the pandemic was the final nail in the coffin, but in many cases, cracks in business models were already starting to surface well before COVID-19 ground the global economy to a screeching halt.

Total Raised: $75 million

Atrium, a 100-person legal tech startup founded by Justin Kan, shut down in March after failing to find an efficient way to replace the arduous systems of law firms. The startup even returned some of its $75.5 million in funding to its investors, including Andreessen Horowitz.

The shutdown comes after the platform had pivoted just months earlier, laying off in-house lawyers and turning into a clearer SaaS play. Ultimately, Atrium’s failure shows how difficult and unprofitable it could be to disrupt a traditional and complicated system.

The closure came just three years after it launched with the goal to build software for startups to navigate fundraising, hiring, acquisition deals and collaboration with their legal team.

Total Raised: $330 million

Image Credits: Darrell Etherington

Big plans, big names and a boatload of money should have been enough to buy Essential a lengthy runway. Sure, Essential was entering a mature and oversaturated market, but the Playground-backed startup was doing so with $330 million in funding, a team of top industry executives and some genuinely innovative ideas.

When I spoke to the company at launch, an executive outlined a 10-year plan to become a major player in both the mobile and smart home categories. Ultimately, the company was able to eke out just under three years of life after coming out of stealth. And while it did give the world a promising handset, its connected home hub never arrived.

Timing, broader marketing issues and troubling allegations of sexual misconduct were all contributing factors that stopped Essential’s big plans dead in their tracks.

Total Raised: $11.4 million

Image Credits: HubHaus

HubHaus, founded by Shruti Merchant, was a long-term housing rental platform rooted in the belief that adult dormitories would take off. The startup targeted working professionals in cities, and raised only around $11 million in known venture capital. When it came to raising a Series B, Merchant says the company struggled to close and lost investor interest due to WeWork’s failed IPO.

After then pivoting to a self-funded company, HubHaus was just finding footing when the coronavirus pandemic arrived in the United States, drastically hurting the rental market (as shown by Airbnb’s public struggles, as well). The housing company eventually decided to close down in September, leaving landlords, members and vendors in limbo and bringing on a fresh sweep of critique and controversy.

Affordable housing continues to be an issue in the Bay Area, and HubHaus’s departure from the scene underscores this truth.

Total Raised: $55 million

Image Credits: Hipmunk

Hipmunk, founded by Adam J. Goldstein and Reddit co-founder Steve Huffman, was one of the first travel aggregation platforms on the market. The company put together information on flights, hotels and car rental all into one place so consumers could compare and contrast prices with ease.

The focus was enough for the platform to get acquired by Concur, but now after four years, the travel startup shut down. Notably, the travel startup’s closure wasn’t necessarily tied to the coronavirus pandemic. The site officially went dark on January 23, months before lockdowns came to the United States.

Total Raised: $51.4 million

Photo: Thomas Barwick/Getty Images

IfOnly had created a marketplaces of exclusive events — such as “goat yoga” — a business that faced obvious challenges during the pandemic. The startup was actually acquired by one of its investors, Mastercard, late last year, but the acquisition wasn’t announced until IfOnly revealed over the summer that it was shutting down.

Mastercard also said IfOnly’s team and technology are still part of its Priceless experience marketplace: “The IfOnly platform will continue to help advance our Priceless strategy and our combined team will be even better positioned and equipped to deliver exclusive experiences for cardholders globally.”

Mixer/Beam Interactive (2014-2020)

Total Raised: $520,000

Image Credits: Microsoft

Microsoft shut down its Twitch competitor Mixer this year, handing off its partnerships to Facebook Gaming. The service had its roots in the software giant’s acquisition of Beam Interactive shortly after the startup won TechCrunch’s Startup Battlefield in 2016.

Before giving up, Microsoft made some big investments in Mixer’s success, most notably signing streaming superstars Ninja and Shroud to exclusive deals. (They became free agents after the shutdown.) However, Microsoft’s gaming chief Phil Spencer said the company suffered from starting out “pretty far behind” the biggest players in the streaming market.

Total Raised: $10.2 million

Image Credits: The Outline

Despite a busy year of innovation and venture for news media platforms, The Outline, which branded itself as “the next generation version of the New Yorker” was shut down. The media site was started by Josh Topolsky and had an explicit focus on serving millennials with a digital-first news media brand.

The shutdown was part of a broader layoffs at Bustle Digital Group, which acquired the publication in 2019. Pre-acquisition, The Outline had already scaled back its editorial staff and refocused on freelance articles. (Input — a tech site that Topolsky founded for BDG — continues to publish.)

Periscope went out with more of a whimper than a bang. The startup was acquired by Twitter before it had even launched a product. With Meerkat bursting on the scene that year at SXSW, Twitter went on the offensive, buying the startup to build out its own live video offering.

Periscope’s run was decent as far as these things go, and its technology will live on as part of Twitter’s video offerings, even after the app is officially discontinued next March. But in the end, Periscope was a shell of its former self. In fact, this is a rare instance where the pandemic may have actually delayed its shutdown.

The company notes, “We probably would have made this decision sooner if it weren’t for all of the projects we reprioritized due to the events of 2020.”

Total Raised: $15.1 million

Image Credits: PicoBrew

The company made beer-brewing machines that used coffee pod-style PicoPaks, then expanded into other categories like coffee and tea, but never quite attracted enough customers to make the business viable. It sold its assets earlier this year to PB Funding Group — a group of lenders recruited by then-CEO Bill Mitchell in 2018 to keep it afloat.

It’s possible that PicoBrew will live on in some form, as PB Funding Group says it’s seeking buyers for the company’s patents and other intellectual property, and that it will keep the website running in the short term so that the machines don’t stop working.

Total Raised: $1.75 billion

Quibi CEO Meg Whitman speaks about the short-form video streaming service for mobile Quibi during a keynote address January 8, 2020 at the 2020 Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo by ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images)

More so than any tech company in recent memory (with the possible exception of Theranos), Quibi’s existence feels like a fever dream. $1.75 billion in funding later and what do we have to show for it? “Fierce Queens,” a nature documentary about female animals. The HGTV-style program, “Murder House Flip.” And, of course, “The Shape of Pasta.” A show about pasta.

Early reports of the service’s demise seemed premature — if only because there was seemingly no way a company could burn through that much capital that quickly. By late-October, however, it was over. “All that is left now is to offer a profound apology for disappointing you and, ultimately, for letting you down,” founders Jeffrey Katzenberg and Meg Whitman wrote in an open letter.

Sometimes startup failures are bad timing. Sometimes it’s just plain bad luck. With Quibi, the diagnoses of what went wrong can be summed up in one word: everything.

Total Raised: $15 million

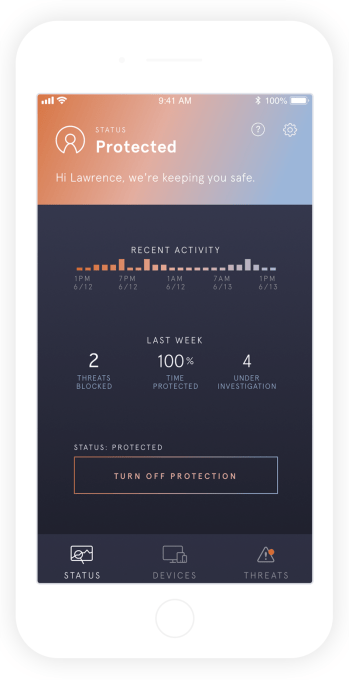

Image Credits: Rubica

Rubica spun out of security company Concentric Advisors with the aim of offering tools that were more advanced than antivirus software, while still remaining accessible to individuals and small businesses. CEO and co-founder Frances Dewing said that when customers cut back on spending during the pandemic, the company tried to shift its focus to larger enterprise, but it failed to convince investors there was a business there.

“We were all really surprised given how relevant and needed this is right now,” she said. “Investors didn’t agree with that or see it in the same way.”

Total Raised: $104 million

Businessman’s hands with calculator and cost at the office and Financial data analyzing counting on wood desk. Image Credits: Sarinya Pinngam/EyeEm / Getty Images

ScaleFactor was a startup claiming to offer artificial intelligence tools that could replace accountants for small businesses; it blamed the pandemic for cutting its revenue in half and forcing the company to shut down. However, former employees and customers told Forbes a different story — that ScaleFactor actually relied on human accountants (including an outsourced team in the Philippines) to do the work.

While it’s hardly unprecedented for a startup to fudge the truth about their level of automation versus human labor, this reportedly resulted in error-filled accounting for ScaleFactor clients. (Responding to a fact-checking email, former CEO Kurt Rathmann said the email was “filled with numerous factual inaccuracies and misrepresentation” and declined to comment further.)

Total Raised: $20 million

Self-driving trucks startup Starksy Robotics began with this first, and problematic truck. Image Credits: Starsky Robotics

“In 2019, our truck became the first fully-unmanned truck to drive on a live highway,” Starsky Robotics co-founder and CEO Stefan Seltz-Axmacher wrote in a Medium post in March. “And in 2020, we’re shutting down.” After five years and $20 million in funding, the autonomous trucking company shut its doors that month. It wasn’t for lack of ambition or demand — it seems safe to assume there’s still a bright future for self-driving trucks.

Ultimately, however, Starsky won’t be along for that ride — a fact Seltz-Axmacher blames largely on timing. A crowded market is certainly at play, as well, with countless companies currently pushing to bring autonomous technology to the road.

Total Raised: $10 million

Image Credits: Bryce Durbin

Founded in 2018 by ex-Googlers, Stockwell AI shut down after being unable to find business for its in-building smart vending machines that stocked everything from condoms to La Croix. The company blamed the “current landscape” (also known as the global pandemic we are experiencing) for its closure.

Stockwell AI, formerly known as Bodega, was well-funded and well-known, with more than $45 million in funding from investors that included NEA, GV, DCM Ventures, Forerunner, First Round and Homebrew. Still, even venture capital couldn’t make vending machines work well enough.

Total Raised: $2.5 million

Image Credits: Trover

Another travel-focused startup bites the dust as the coronavirus limits the chance to safely explore the world (let alone your neighborhood). Trover, a photo-sharing hub for travelers acquired by Expedia, shut down in August. The startup was founded by Rich Barton and Jason Karas and was meant to connect people travelling to the same places. The startup had quite the life: it began out of the remains of TravelPost, a travel review site, and got scooped up by its parent company when it only had $2.5 million in funding. Unfortunately, its nine-year journey is over for now.

Powered by WPeMatico

Google said on Tuesday it is investing in two Indian startups, Glance and DailyHunt, as the Android-maker makes a further push into the world’s second-largest internet market.

Two-year-old Indian startup Glance, which serves news, media content and games on the lock screen of more than 100 million smartphones, has raised $145 million in a new financing round from Google and existing investor Mithril Partners.

Glance, which is part of advertising giant InMobi Group, uses AI to offer personalized experience to its users. The service replaces the otherwise empty lock screen with locally relevant news, stories and casual games. Late last year, InMobi acquired Roposo, a Gurgaon-headquartered startup, that has enabled it to introduce short-form videos on the platform. Google is also investing in Roposo.

Roposo is a short-video platform with more than 33 million monthly active users. These users spend about 20 minutes consuming content across multiple genres in more than 10 languages on the app everyday.

Glance ships pre-installed on several smartphone models. The subsidiary maintains tie-ups with nearly every top Android smartphone vendor, including Xiaomi and Samsung, the two largest smartphone vendors in India. The service has amassed over 115 million daily active users.

“Glance is a great example of innovation solving for mobile-first and mobile-only consumption, serving content across many of India’s local languages,” said Caesar Sengupta, VP, Google, in a statement. “Still too many Indians have trouble finding content to read or services they can use confidently, in their own language. And this significantly limits the value of the internet for them, particularly at a time like this when the internet is the lifeline of so many people. This investment underlines our strong belief in working with India’s innovative startups and work towards the shared goal of building a truly inclusive digital economy that will benefit everyone.”

Naveen Tewari, founder and chief executive of Glance and InMobi Group, said the investment will pave the way for “deeper partnership between Google and Glance across product development, infrastructure, and global market expansion.” The startup plans to deploy the fresh capital to expand in the U.S.

Google said on Tuesday that it is also investing in VerSe Innovation, the parent firm of Indian startup DailyHunt. Across its apps including eponymous service and short-video platform Josh, DailyHunt claims to serve over 300 million users news and entertainment content in 14 Indian languages. The startup said it has completed a round of over $100 million from Google, Microsoft and AlphaWave among other investors, and this new round values it at over $1 billion, making it a unicorn.

DailyHunt — which is co-run by Umang Bedi, former Facebook India head — plans to deploy the fresh capital to scale the Josh app, the augmentation of local language content offerings, the development of content creator ecosystem, innovation in AI and ML and the growth of its truly “made-in-Bharat-for-Bharat short-video platform,” it said.

Josh and Roposo are among over a dozen apps in India that are attempting to fill the void New Delhi created after banning TikTok in late June in the country. TikTok identified India as its biggest overseas market prior to the ban.

Google is writing both these checks from India Digitization Fund that it unveiled this year. Google has committed to invest $10 billion in India over the course of the next few years. Prior to today, the company invested $4.5 billion from this fund in Indian telecom giant Jio Platforms.

Powered by WPeMatico

Mobile travel app Hopper has been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic as consumers canceled their trips and airlines dropped their flights. But the complications around getting airline credits and refunds have since turned into a customer service crisis for the airfare prediction and ticket booking startup, which had been valued at $750 million back in 2018 before reaching unicorn status thanks to an undisclosed round it closed amid COVID lockdowns this year. Currently, hundreds of Hopper customers are trashing the app in their app store reviews, calling Hopper a scam, threatening legal action and warning others to stay away.

The key complaint among many of these users was not only how their flight was canceled by an airline and that they couldn’t get a refund, but that there was no way to get in touch with someone at Hopper for any help. There wasn’t even a phone number to call, the user reviews said.

These complaints on the app stores have been harsh and a PR disaster for Hopper’s brand.

To give you an idea of what’s being said, here’s a small sampling:

To date, users have left more than 550 one-star reviews on iOS and 302 on Android, per Sensor Tower data. Hundreds of these are visible when you sort by “Most Recent” reviews on iOS, which is damaging to what had been, before the pandemic, a trusted and respected travel brand.

@.sp2020##hopper is getting trashed — no customer support? Can’t get refund? ##covid ##travel♬ Trouble’s Coming – Royal Blood

Hopper, to its credit, openly admitted to TechCrunch it’s been massively struggling with what it referred to as “unprecedented volumes of customer support inquiries since the start of the pandemic began,” or 2.5X its normal rate.

The company says it’s currently receiving over 100,000 inbound support requests per month, as consumers and airlines alike changed and canceled their flights. Since April, it’s seen over 980,000 inbound customer service requests.

A number of the inquiries are from customers asking for refunds due to COVID-related cancellations. Typically, airlines offer a modified flight when they make a schedule change, and many consumers will take this modification. Some customers, however, will want a refund so they can rebook a different flight or because they’ve chosen to cancel their travel plans entirely. The pandemic has exacerbated this problem, driving cancelation rates around five times higher than usual, Hopper says.

Another point of confusion is who should handle these refunds. Hopper says customers can either reach out to the airline directly for a refund for help rebooking or they can ask Hopper to handle it. It also noted a small number of airlines don’t allow refunds, only travel credit. The airlines dictate these policies, which means Hopper can’t just offer to refund everyone — it would have lost too much money to survive, if it did so.

“We would have had to put out about half a billion dollars,” explains Hopper CEO Frederic Lalonde, describing the situation to TechCrunch. We had reached out to understand the situation, given the sizable customer backlash against the previously popular app.

“The way the airline system works is if I refund you as a customer who booked from us, I’m not going to get that money back. We would have put ourselves out of business,” Lalonde says.

In addition, Hopper doesn’t generally receive the refunds itself. They go directly from the airline to the customer. And many customers had to wait on refunds this year due to COVID issues. But there are some exceptions. For a few low-cost carriers, like Frontier, Spirit and others, Hopper does have to process the refund from the airline and then return these to the customers. So in these cases, Hopper’s non-responses to customer support inquiries left customers without options. (We’re documenting how the airlines are responding to our inquires about Hopper refunds here. It’s confusing, to say the least.)

But the root of Hopper’s customer service nightmare wasn’t the chaos caused by the pandemic and the airlines’ cancellations themselves. It was how Hopper approached handling the situation.

“We failed our customers,” Lalonde admits. “We had a bunch of people that trusted us.”

He said Hopper has now addressed many of the customer complaints and issues. But many more still remain. “There’s no universe where that’s what we set out to do,” he adds.

During the course of the year as the customer service crisis escalated, Lalonde says his personal email and mobile phone was published on the web. He’s since opened up several thousands — or maybe even tens of thousands — of emails and voicemails of customers in need of assistance.

In hindsight, one misstep Hopper made is that it didn’t hire more customer service agents to deal with what the pandemic would bring. In fact, Hopper did the opposite — the company furloughed agents in an effort to cut costs and stay in business. At the time, Lalonde explains, there was just too much uncertainty to hire. Stores were out of toilet paper. The Western world had closed for travel. Vaccines had typically taken years to create. This was looking like a long-term, worst-case scenario.

“We had to build an operational plan of zero dollars of revenue for four years. That’s what I gave my board,” Lalonde says.

When lockdowns lifted and travel started to come back, so did some of Hopper’s agents. But the customer service issues, by then, had skyrocketed as airlines canceled and changed schedules at high rates, and began to issue Future Travel Credits (FTC). Instead of adding more agents to help solve customer service problems, Hopper decided to apply automation, with a goal of allowing customers to solve more themselves. During the course of 2020, Hopper automated exchanging flights in the app, redeeming FTC issued by airlines, managing schedule changes, adding self-serve cancellations, and it rolled out follow-up emails to customers after they requested a cancellation.

Lalonde had believed automation would ultimately be more critical to long-term survival than hiring more agents.

“Would it have made a big difference [to add more agents]? Honestly, I don’t really think so. I think it would maybe have gotten 10% more done,” says Lalonde. “Could you find thousands of customers that would have gotten [help] sooner? Yes. But would it really have moved the needle on the millionth inbound request we got? No.”

Another area where Hopper fell short was on customer communication.

This is most apparent from the App Store complaints.

Customers may be expressing frustration over refunds, but they’re even angrier that they can’t get in touch with anyone. And Hopper didn’t necessarily do itself any favors here by sending out emails which said it was aiming to get back to customers within 24 hours — an entirely unrealistic promise (see below).

Image Credits: Hopper email (provided by customer) / Hopper email (provided by customer)

Hopper also chose to shut down its phone line when it realized that 80% of customers were waiting on hold for 45 minutes, even though, arguably, some customers would have preferred that to nothing at all. Instead, it rolled out an online structured triage system that helped prioritize incoming complaints. It even had a button to push if users were stuck at the airport so they could get more urgent assistance.

The problem was customers couldn’t find Hopper’s help features.

“Was our communication strategy broken? Yes,” admits Lalonde.

He says he decided to put the team on actually dealing with the FTC and the refunds, and not talking to people. “That made us look a hell of a lot worse, optically, but we got through a lot of work…because at the end of the day, after the fifth repetitive email, people got just as angry [as when they were ignored].”

Hopper has since apologized to customers and sent out an additional $1.5 million in travel credits to its customers, in addition to the refunds it has now processed, to help make up for its issues. It’s still working through the backlog of customer service issues. And it expects another good six months of chaos as the vaccines shipping now aren’t immediately going to solve the airlines’ travel problem.

Over the next two months, Hopper also says it will be increasing its support team by 75% now that the future looks more certain. It also plans to roll out in-app updates including a resolution center, escalation path, status check to prevent duplicate requests and add in-app structured requests, in addition to more communication updates involving email campaigns, better in-app messaging, and website access to check on booking status.

It’s a wonder how a company in this nightmare situation could even survive, much less raise funds, when its brand is being dragged through the mud and hundreds — or even thousands — of customers have been unsatisfied.

As it turns out, Montreal-headquartered Hopper will survive, at least in the near-term, thanks to a Canadian government bailout.

In early May, Hopper raised $70 million from both institutional and private investors. The Canadian government chose to save promising tech business impacted by the pandemic with direct financial support. The largest portion of the $70 million round (more than half, but not, say, 99%) included funds from the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) and Investissement Quebec. In addition, all of Hopper’s existing investors returned, joined by new investors Inovia and WestCap.

The Canadian government — which Lalonde describes as “more like socialists than you would think” — helped by de-risking the other investors by leading venture rounds into tech businesses that had been doing well pre-pandemic.

“They did this at a very large scale and it’s stabilized the tech sector in Canada,” he says. The new funds now value Hopper “right at unicorn level” in U.S. dollars, Lalonde adds, meaning the business is valued around $1 billion.

One reason why Hopper may have struggled with how to proceed during the pandemic was the sizable uncertainty around the U.S. market, which Lalonde says was “very scary.”

“We never knew what was going to happen. If there had been a better plan there, we probably would have been able to provision a bit more. But we had no idea. The lockdowns were at the state level,” he explains. “If you’re trying to figure out how aggressive you want to be on investing, spending, emergency injections, or how things are going to recover, the more predictability there is at the government level, the easier it is to make a decision. The U.S. wasn’t the most predictable environment,” Lalonde says.

While Hopper’s business is saved for now, the app’s brand reputation has taken a huge hit.

The question now is whether that, too, is recoverable?

“I don’t know,” says Lalonde. “I’ll tell you this, the only right way to approach that is just keep doing the right thing, one customer at a time.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Zomato has raised $660 million in a financing round that it kicked off last year as the Indian food delivery startup prepares to go public next year.

The Indian startup said Tiger Global, Kora, Luxor, Fidelity (FMR), D1 Capital, Baillie Gifford, Mirae and Steadview participated in the round — a Series J — which gives Zomato a post-money valuation of $3.9 billion. Zomato had previously disclosed a fundraise of about $212 million as part of a Series J round from Ant Financial, Tiger Global, Baillie Gifford and Temasek.

Deepinder Goyal, the co-founder and chief executive of Zomato, said the 12-year-old startup is also in the process of closing a $140 million secondary transaction. “As part of this transaction, we have already provided liquidity worth $30m to our ex-employees,” he tweeted.

The startup originally anticipated to close a round of about $600 million by January this year, but several obstacles, including the current pandemic, delayed the fundraise effort. Additionally, Ant Financial, which had originally committed to invest $150 million in this round, only delivered a third of it, Zomato’s investor Info Edge disclosed earlier this year.

The Gurgaon-headquartered startup, which acquired the Indian food delivery business of Uber early this year, competes with Prosus Ventures-backed Swiggy in India. A third player, Amazon, has also emerged in the market, though it currently offers its food delivery service in only parts of Bangalore.

At stake is India’s food delivery market, which analysts at Bernstein expect to balloon to be worth $12 billion by 2022, they wrote in a report to clients — accessed by TechCrunch. With about 50% of the market share, Zomato is the current leader among the three, Bernstein analysts wrote.

Zomato eliminated hundreds of jobs this year to improve its finances and navigate the coronavirus pandemic, which significantly hurt the food delivery business in India in the early months. Goyal said the food delivery market is “rapidly coming out of COVID-19 shadows. December 2020 is expected to be the highest ever GMV month in our history. We are now clocking ~25% higher GMV than our previous peaks in February 2020.” He added, “I am supremely excited about what lies ahead and the impact that we will create for our customers, delivery partners, and restaurant partners.”

In September, Goyal told employees that Zomato was working for its IPO for “sometime in the first half of next year” and was raising money to build a war-chest for “future M&A, and fighting off any mischief or price wars from our competition in various areas of our business.”

Making money with food delivery has been especially challenging in India. Unlike Western markets such as the U.S., where the value of each delivery item is about $33, in India, a similar item carries the price tag of $4, according to estimates by Bangalore-based research firm RedSeer.

“The problem is that there are very few people in India who can afford to place an order from a food delivery firm each day,” said Anand Lunia, a venture capitalist at India Quotient, in an interview with TechCrunch earlier this year.

Powered by WPeMatico

After spending more than a decade disrupting the neighborhood stores in the U.S. and several other markets, Amazon and Walmart are employing an unusual strategy in India to face off this competitor: Friending them.

Walmart and Amazon, both of which face restrictions from New Delhi on what all they could do in India, have partnered with tens of thousands of neighborhood stores in the world’s second-largest internet market this year to leverage the vast presence of these mom and pop stores.

In June this year, at the height of the pandemic, Amazon announced “Smart Stores.” Through this India-specific program, for instance, Amazon is providing physical stores with software to maintain a digital log of the inventory they have in the shop and supplying them with a QR code.

When consumers walk to the store and scan this QR code with the Amazon app, they see everything the shop has to offer, in addition to any discounts and past reviews from customers. They can select the items and pay for it using Amazon Pay. Amazon Pay in India supports a range of payments services, including the popular UPI, and debit and credit cards.

The world’s largest e-commerce giant also maintains partnerships that allow it to turn tens of thousands of neighborhood stores as its delivery point for customers — and sometimes even rely on them for inventory.

India has over 60 million small businesses that dot the thousands of cities, towns and villages across the country. These mom and pop stores offer all kinds of items, are family run, and pay low wages and little to no rent.

This has enabled them to operate at an economics that is better than most — if not all — of their digital counterparts, and their scale allows them to offer unmatched fast delivery.

Krishna Shah, a New Delhi-based doctor, on paper is one of the perfect customers of e-commerce services. She lives in an urban city, uses digital payments apps and her earnings put her in the top 5% income level in the country. Yet, when she needed to buy food for her cats and needed it as soon as possible, she realized the major giants would take hours, if not longer. She ended up placing a call to a neighborhood store, which delivered the item within 10 minutes.

That neighborhood store, which employs fewer than half a dozen people, was competing with over a dozen giants and heavily funded startups including Grofers and BigBasket — and it won.

At stake is India’s retail market, which is estimated to be worth $1.3 trillion by 2025, from about $700 billion last year, according to Boston Consulting Group and the Retailers’ Association India. E-commerce, by several estimates, accounts for just 3% of the retail market in the country.

If that figure wasn’t small enough already, consider this: Some of the biggest customers of Flipkart and Amazon are these small retail stores. An executive with direct knowledge of the matter told TechCrunch that during some sales, as high as 40% of all smartphone units are bought by physical stores. The idea is, the executive said, to buy the devices at a discounted price, sit on them for a few days and when Amazon and Flipkart are done with their sales, sell the same phones at their standard prices.

Sujeet Kumar, co-founder of Udaan, a Bangalore-based startup that works with merchants, said that even as smartphones and the internet have reached all corners of India, e-commerce hasn’t been able to disrupt the retail market.

“The problem is that it is very difficult for e-commerce companies to build a supply chain and distribution network that is more efficient than those established by neighborhood stores. These mom and pop stores operate on an insanely different kind of cost economics. E-commerce companies are not able to match it,” he said.

Powered by WPeMatico

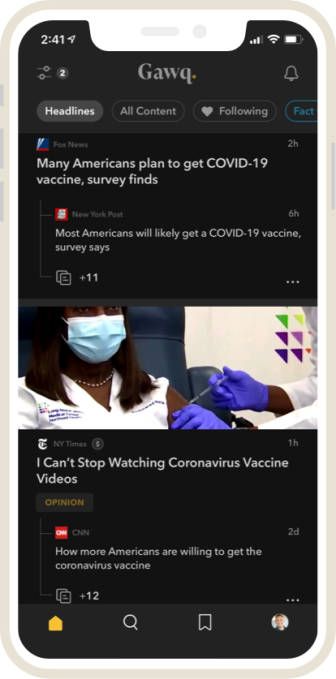

A new startup called Gawq wants to tackle the problem of fake news and the “echo chamber” problem created by social media, where our view of the world is shaped by manipulative algorithms and personalized feeds. Through Gawq’s newly launched mobile news app, it aims to present news from a range of sources, while allowing users to filter between news, opinion, paid content and more, as well as compare sources, check facts and even review the publication’s content for accuracy.

The idea for Gawq comes from Joshua Dziabiak, co-founder and now board member at the now profitable insurance tech startup The Zebra. Dziabiak stepped down from his day-to-day role this March, and founded Gawq shortly after.

“It started as a passion project and then it transformed into a business,” Dziabiak explains. “I wanted to do something that had a larger social impact. And this idea — this problem — has surfaced and been magnified in really big ways over the past year, especially,” he says.

When news is served up through social media channels, people are presented with their own version of reality, as the algorithms begin to filter out the news that doesn’t engage them and show them more of what does. Over time, this system led some publishers to pursue clicks and outrage with over-the-top, sensational headlines, but it also spawned a network of publications that would slant and bias the news in ways that better connected them with an either right or left-leaning audience.

As a result, the media environment overall began to center itself around eyeballs and not necessarily news quality, Dziabiak says. While there is still quality journalism being created, it can sometimes be hard to find among all the noise.

“I believe journalists and content creators need a new measure for success. One that is based on the core ethics of journalism, and not the number of clicks or shares,” Dziabiak notes.

Image Credits: Gawq

The Gawq name is meant to be a reminder of how today’s headlines often scream for our attention. But it misses the mark for an app about news accuracy. At its core, Gawq is a news aggregator where you are not meant to “gawk” at headlines, but actually read and consider the news with a more critical eye.

At launch, the app organizes more than 150 different top media sources of all types and sizes, including those that lean one way or the other. The publishers cover topics like U.S. and world news, politics, sports, business, tech, entertainment, science, lifestyle news and more.

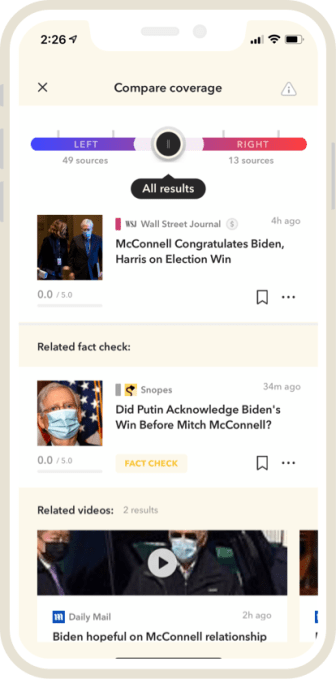

Gawq also organizes the day’s news without using any sort of algorithms or personalization engines, but instead by topic. As you read, you click to compare coverage of the story with other sources to get a better idea of how different outlets are writing about the same topic. With a clever red and blue slider bar at the top of the screen, you can drag your finger over to the red side to see the coverage from right-leaning sources, or you can drag it to the blue side to see the more left-leaning coverage.

The company says it uses data from three different nonprofits that audit media — AllSides, Media Bias Fact Check and Ad Fontes Media — to determine if sources are “right” or “left.”

Image Credits: Gawq

Just below the slider bar are the related fact checks to the topic at hand, for easy reference.

While Gawq will allow users to toggle some news sources on or off within the app’s settings, it uses language that deters you from doing so by reminding you that it works best when you maintain a “diverse set of media.”

In addition, Gawq introduces a “smart labels” feature to automatically identify and tag non-news — like op-ed’s, sponsored content or even celeb gossip, if you hate that sort of thing. You can toggle these on or off, too, if you want to hide anything that’s not hard news.

Another nice feature — for the news consumer at least, if not the publisher — is that Gawq loads articles by default into a “reader mode” that strips the ads and distractions that tend to fill the pages on news websites these days. You can still click to view the article on the website, if you prefer.

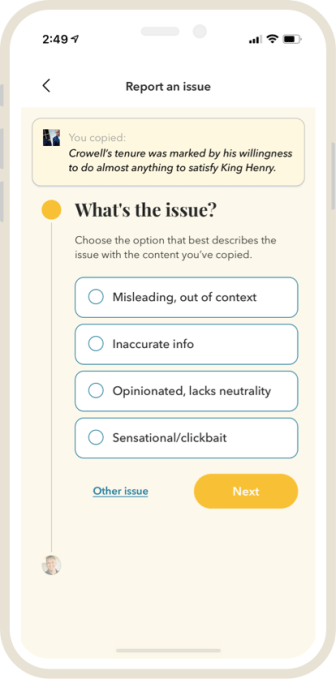

While much of the above is related to how the news is presented to the reader, Gawq’s bigger bet is that it can create a Wikipedia-like community of news reviewers who will rate stories for adherence to journalistic practices. This is a more ambitious and perhaps overly optimistic endeavor.

On every article, users can click a review button that walks them through a short quiz where they’re asked to rate the story’s balance, the details provided and whether the headline was clickbait. Users then add a comment and submit their report. This review process was built off the core ethics of journalism as defined by the Society of Professional Journalists, Dziabiak says.

Image Credits: Gawq

Likely, only a minority of Gawq users would rate the stories. But over time and with scale, the reviews could help give outlets an accurate rating on news accuracy and their tendencies toward sensationalism, in the eyes of news consumers. That data may have external value, but for now, Gawq’s business model is “TBD,” Dziabiak admits.

The problem Gawq aims to tackle is a difficult one. And arguably, those who need to widen their worldview will be least likely to download a new app to do so. They’re often passive news consumers who have sat back ingesting news (and often, outrage and lies) from ever-personalized social media feeds. They then click on one favorite news TV channel for everything else. But there is a growing number of people who want a more neutral media landscape, and Gawq can help them find it with how it positions news as right, left or centered when comparing sources.

The startup is currently self-funded and has a small team of engineers, mostly working on a contract basis. Gawq has not ruled out future investment, however.

The app is a free download on iOS and Android.

Powered by WPeMatico

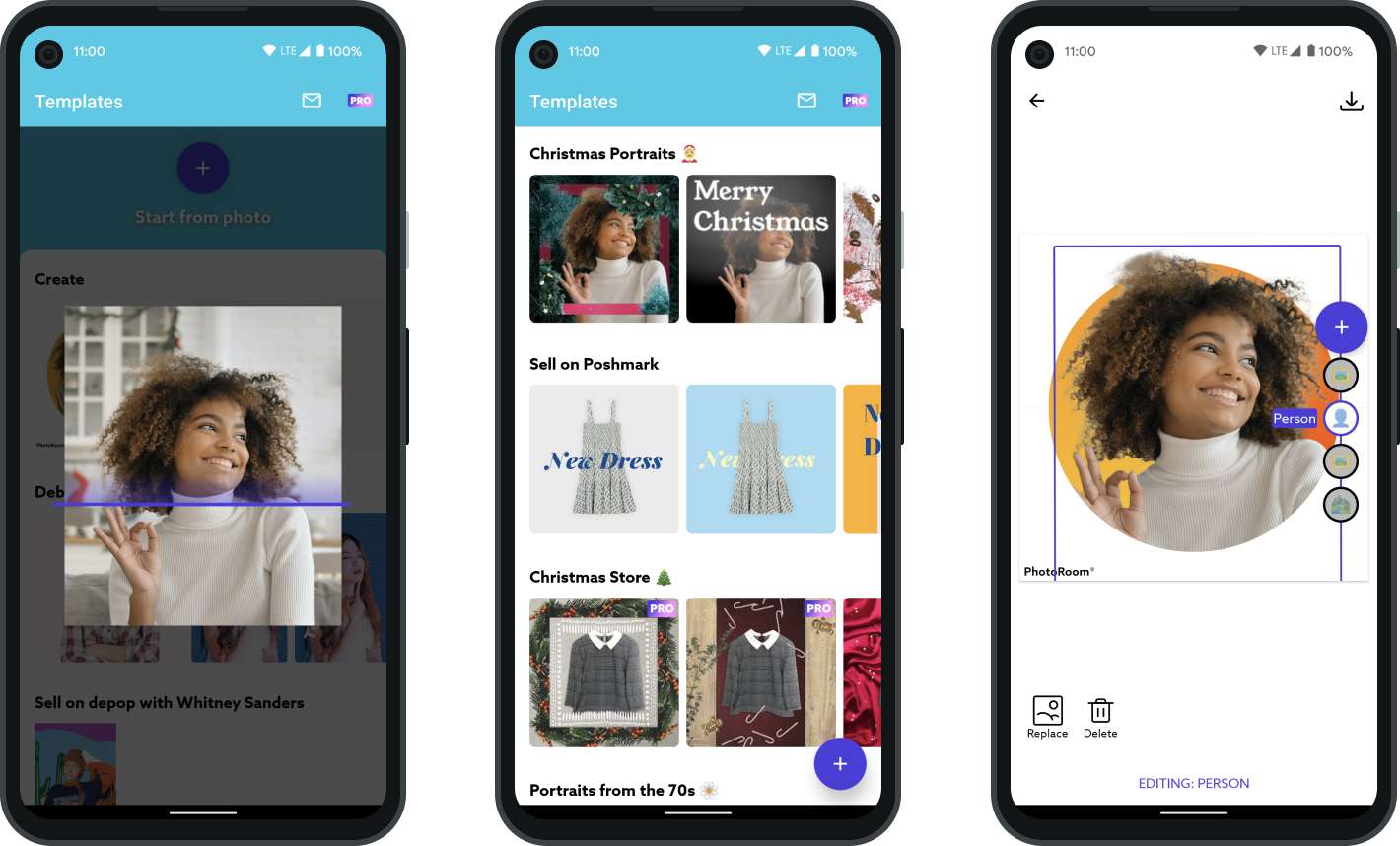

French startup PhotoRoom is launching its app on Android today. The company has been working on a utility photography app that lets you remove the background from a photo, swaps it for another background and tweaks your photo.

And it’s been working well on iOS already, as the company attended Y Combinator, doubled its annual recurring revenue to $2 million and raised a $1.2 million seed round.

In particular, influencers and people reselling clothes and fashion items have been relying on PhotoRoom . They use their phone as their main creativity platform. Like other professional photography apps, the startup relies on subscriptions to generate revenue ($9.49 per month or $46.99 per year).

PhotoRoom relies on machine learning to identify objects and separate them from the rest of the photo. This way, you can manipulate a specific part of your photo.

Image Credits: PhotoRoom

When the startup raised its seed round after Y Combinator, it chose to raise from Nicolas Wittenborn’s Adjacent fund, Liquid2 Ventures, as well as two groups:

With this funding round, the company plans to grow the team from three to eight persons and work on its deep learning algorithm. If you want to learn more about PhotoRoom, feel free to read my take on the product:

Powered by WPeMatico

Andreas Pursian, Markus Gilles and Jonas Brandau, the three co-founders of Klima, an app focused on helping consumers understand and offset their carbon emissions, first found entrepreneurial success at Hyper.

The mobile magazine publishing toolkit they developed was sold to Mic in 2017, but it was only the most recent success in a string of collaborations dating back nearly a decade.

“We had a fascination for technology and all the great things you could do to improve society,” said Gilles, Klima’s chief executive, in an interview earlier this year.

Klima, which launched this month, is in some way the culmination of those efforts.

Gilles and Pursian first met in university and later with Brandau they launched their first app, Pino, a mobile-based video op-ed page that had German Chancellor Angela Merkel as an early contributor on the platform.

The connection to politics and media continued with Hyper, their publishing platform that sold to Mic, and continues with Klima. With the app, the three co-founders have taken their media savvy and applied it to getting consumers to reduce and neutralize their carbon emissions through offsets and behavioral changes.

“Offsets can remedy and buy us a lot of time while we’re rebuilding our society,” said Gilles. “We need to get to 50% emissions reductions in the next 10 years which is a herculean task. We can’t afford to leave any climate solution on the table right now.”

Like other apps, Klima has identified diet as one of the major personal steps a person can take to reduce their emissions footprint. Substituting cars with biking, or electric vehicles, and buying less fast-fashion and more used clothing also has an impact.

Klima’s app includes a carbon calculator, which measures a carbon footprint and allows users to offset that with a personalized monthly subscription. The company’s app also provides lifestyle tips to reduce emissions. Finally it offers a social sharing feature so that other would-be climate warriors can join the fight to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

“We have a special situation right now,” said Gilles. “What we are doing as founders. We know that the climate crisis is not taking a pause because of the pandemic. We have raised enough funding right now to still be there when the pandemic is over.”

The company is backed by Jens Begemann, the founder of Wooga; Niklas Jansen, co-founder of Blinkist; Christian Reber, the founder of Pitch; and institutional investors including e.ventures, HV Holtzbrinck Ventures and 468 Capital.

To date, Klima has raised $5.8 million in financing. The company offers three types of offsets for its users. The first is natural solutions, like tree-planting projects; the second is tech-based solutions like solar power installations; and the third is social solutions, like replacing wood-burning cookstoves with electric or gas stoves for homes.

“We’ve seen great traction with the app so far,” said Gilles. The company’s app is now live in 18 countries including the U.S., Canada, Australia and New Zealand, and has the largest user base of any climate offset app currently on the market, the company said.

Powered by WPeMatico

Sanchali Pal first woke up to the world’s climate crisis after watching the 2008 documentary Food Inc.

The Princeton undergraduate saw the film in 2011, and it started her on the journey that would lead her to launch Joro, the Sequoia-backed startup that monitors consumer spending to offer tips on how to offset and reduce a user’s carbon footprint.

After scoring a job at the development firm Dalberg, then working in India and Ethiopia, Pal returned to the U.S. to pursue an MBA at Harvard Business School. She initially thought she’d focus on transportation, but her mind kept returning to consumer consumption habits and the potential to reduce CO2 emissions by targeting consumer behavior.

“I started thinking about it in the fall of my first year at business school, and I kind of put it on the back burner because I didn’t know how to do it from a practical stand. I wasn’t a technology person. I didn’t build software myself,” Pal told Jason Jacobs, the host of the My Climate Journey podcast. “I didn’t know how we would capture the data to show someone their carbon footprint and help them reduce it until I met my co-founder [J. Cressica Brazier], and I met her at an MIT event in the spring of that year two years ago, and the wheels started turning, maybe there’s a tool here that we could build together.”

The Joro app uses consumer spending data culled from integrations with Plaid to identify changes in users’ personal habits that can make an impact on their overall carbon footprint — based on their personal spending.

The app also has a community component, connecting users with sustainability challenges, classes and other educational tools, along with a social network to communicate with peers to track relative progress.

Consider it a version of keeping up with the Joneses, but for planetary health and eco-consciousness.

To date, the app’s community of users have reduced nearly 6 million kilograms of carbon dioxide emissions in 2020. Which sounds impressive, but given reductions in travel due to COVID-19 mitigation restrictions, the largest contribution that a consumer can make is reducing their meat consumption. While that only leads to roughly 4% reductions in global carbon emissions, it reduces about 1,200 pounds of carbon emissions. Over the 6 million kilograms that would mean a little bit over 10,000 people may be using the app.

Pal would not comment on the number of users her company’s app has managed to attract.

Image Credit: Joro

What the company does have now is $2.5 million in seed funding from investors including Sequoia Capital, which doubled down on its $1 million pre-seed commitment made when Joro was part of the firm’s early-stage founder program.

Other investors and advisors include the venture firms Expa and Amasia, and angel investors and advisors like James Park, the co-founder of Fitbit; Rich Pierson, the co-founder of Headspace; Sebastian Knutsson, the chief creative head and co-founder of King; the actress Maisie Williams; Philian, the private investment company of Karl-Johan Persson, chairman of H&M; Tom Baruch; and Anjula Acharia, a partner at Trinity Ventures.

“At Expa we are focused on backing remarkable founders that are passionate about the product they are building,” said Expa founder Garrett Camp in a statement. “We saw that in Sanchali – she had a big vision and conveyed it very strongly to us. We have conviction that Joro can build a great product and a great business. The world will be a better place because of what Joro will bring to market.”

Pal estimates that behavioral changes and better consumer choices can reduce an individual’s carbon footprint by up to 30%.

It’s a bet that other companies are making too. For instance, the Los Angeles challenger bank Aspiration, founded by Andrei Cherny, has a tool that can measure the “social impact” of a consumer’s monthly spending — that includes the climate impact of daily consumption.

Pal hopes that through the education and community components of the app, consumers can put pressure on the systems and industries that are the primary producers of greenhouse gas emissions to change their ways.

“Systems are made of people. Like us,” Pal wrote in a blog post. “Companies and governments change when enough people demand it through their actions and behaviors. No, we’re not a silver bullet — we need policymakers and businesses to take sweeping action. But we’re not powerless either. Together we can accelerate the pace of change by demonstrating our demand for a cleaner society.”

Powered by WPeMatico

Demand for contactless payments and e-commerce has grown in South Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is good news for payment service operators, but the market is very fragmented, so adding payment options is a time-consuming process for many merchants. CHAI wants to fix this with an API that enables companies to accept over 20 payment systems. The Seoul-based startup announced today it has raised a $60 million Series B.

The round was led by Hanhwa Investment & Securities, with participation from SoftBank Ventures Asia (the early-stage venture capital arm of SoftBank Group), SK Networks, Aarden Partners and other strategic partners. It brings CHAI’s total funding to $75 million, including a $15 million Series A in February.

Last month, the Bank of Korea, South Korea’s central bank, released a report showing that ()contactless payments increased 17% year-over-year since the start of COVID-19.

CHAI serves e-commerce companies with an API called I’mport, that allows them to accept payments from over twenty options, including debit and credit cards through local payment gateways, digital wallets, wire transfers, carrier billings and PayPal. It is now used by 2,200 merchants, including Nike Korea and Philip Morris Korea.

CHAI chief executive officer Daniel Shin told TechCrunch that businesses would usually have to integrate each kind of online payment type separately, so I’mport saves its clients a lot of time.

The company also offers its own digital wallet and debit card called the CHAI Card, which launched in June 2019 and now has 2.5 million users, a small number compared South Korea’s leading digital wallets, which include Samsung Pay, Naver Pay, Kakao Pay and Toss.

“CHAI is a late comer to Korea’s digital payments market, but we saw a unique opportunity to offer value,” said Shin. The CHAI Card offers merchants a lower transaction fee than other cards and users typically check its app about 20 times to see new cashback offers and other rewards based on how often they pay with their cards or digital wallet.

“We’ve digitized the plastic card experience, and this is the first step towards creating a robust online rewards platform,” Shin added.

In press statement, Hanhwa Investment & Securities director SeungYoung Oh director said, “I’mport has reduced what once took e-commerce businesses weeks to complete into a simple copy-and-paste task, radically reducing costs. It is a first-of-its-kind business model in Korea, and I have no doubt that CHAI will continue to grow this service into an essential infrastructure of the global fintech landscape.”

Powered by WPeMatico